“He encouraged me to make a lot of positive changes in my life,” Imran said when I met him at a Domino’s near his college, the Vignana Jyoti Institute of Engineering and Technology in Hyderabad. He showed me his phone’s wallpaper: a picture of the two of them outside a pool, grinning with their thumbs up, Imran’s wiry frame contrasting with Akash’s sturdier figure. “I miss him more than anyone will ever understand.”

On June 8 of last year, during a college field visit to Himachal Pradesh, Akash and 23 other students drowned in the Beas River when a dam upstream released a torrent of excess water. The sudden loss of his friend and classmates devastated Imran, who was there. Memories of Akash constantly haunted his thoughts. His grades slipped. He shut himself off from the rest of the student body, often sleeping through the days and feeling utterly alone.

Imran was showing signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, but Vignana Jyothi, already strained under litigation from the tragedy, offered him little by way of professional help. The campus had a psychologist, but at Rs 1,000 per session, it was too expensive for a scholarship student like Imran.

A silent crisis

Imran's experience is part of a wider national problem: there are only about 5,000 licensed therapists in the entire country, according to the Public Health Foundation of India. In schools and universities, the lack of mental health support can combine with intense academic pressures to result in a toxic mix. India has one of the highest youth suicide rates in the world, and police have linked a recent spate of student suicides in Hyderabad to an academic environment where children are pushed to study for 18 hours per day. Even in elite institutions that have better facilities, mental health often falls by the wayside. Over half of all IITs don’t have a full-time counsellor on campus, while a 2013 study found that fully 40% of medical students in Karnataka suffer from untreated depression.

“Schools do care about their students’ mental health, but they’re stretched for funds,” said Nitya Kanuri, a researcher with the Laboratory for the Study of Behavioral Medicine at Stanford University in California. “The way the system works, students are three people deep [before they can access care] and they’re thinking, I have these huge problems that no one can solve. And if no one comes to see counsellors anyway, the assumption is that mental health is not a problem.”

Mobile technology could provide a solution. Kanuri was studying mobile app-based mental healthcare in the US when, last year, she thought of bringing the project to India. Her Mana Maali initiative provides students with mental health support through applications they can access online and on their phones – a cheaper and more confidential alternative to hiring more counsellors.

For now, the program is part of a Stanford study, as a pilot trial limited to two colleges in Hyderabad – Imran’s school, Vignana Jyoti, and the Birla Institute of Technology and Science – but it has already generated remarkable interest. In January, when Kanuri, who is just 24, asked students to take part in the trial, over a thousand signed up. They were grouped into different categories of stress levels based on their responses to a survey. Students with PTSD – like Imran, who made up about 6% of the group – were referred to therapists hired by the study. Participants who demonstrated clinical levels of anxiety, about a quarter of the remaining group, were given access to the app. This way, students with complex disorders receive face-to-face therapy, while those with anxiety – a relatively simpler and more common condition – can still receive confidential virtual support.

“The beauty of this process is the measurement,” said Dr DN Rao, the general secretary of the society that runs Vignana Jyoti. “It lets us identify those students who need help, so that we can reach them in the right way.”

Mapping moods

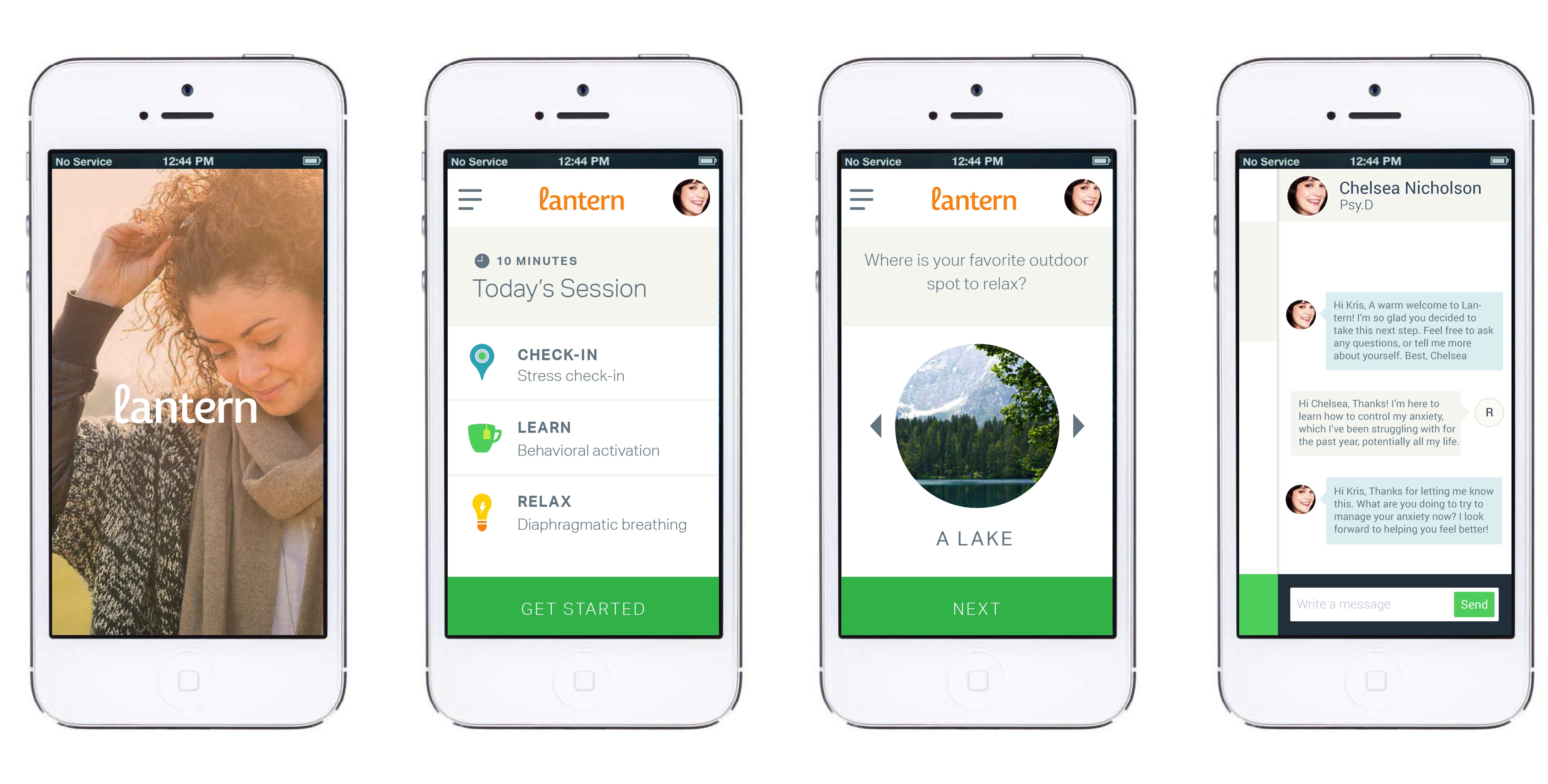

The app that Mana Maali uses is called Lantern, which offers structured, 10-minute modules that ask users about their mood and anxiety levels, and then recommends a specific technique like relaxation to help them manage their stress.

Some users are also assigned trained “coaches”, who counsel them through a messenger built into the app. This method, known as guided self-help, mirrors cognitive behavioral therapy, which helps people disassociate normal situations from real dangers, since anxiety can make even everyday irritations like traffic or alarm bells feel like intense threats.

“Generally, guided self-help gets the exact same results as face-to-face therapy,” said Dr Craig Barr Taylor, a psychiatrist at Stanford who is overseeing the Mana Maali study. “And you have the advantages of easier access, less stigma and lower cost.” For now, Lantern only works with anxiety, although Dr Taylor believes the scope of guided self-help programs is bound to expand in the future.

Personal coach

Rohan, an engineering student at BITS, said he felt uncomfortable with the culture of “slogging” at his university, and that no matter how hard he studied, his grades never seemed to improve. He couldn’t take the courses that interested him and that compounded his anxiety. After signing up with Mana Maali, he has been using the Latern app and communicating daily with a coach, which he says has been helpful.

“My friends and family say they’ve noticed some positive changes in me,” Rohan told me. “I realised that instead of feeling sad about the things that I could have done but didn’t, I should look forward to the things that I can do.”

“I basically text my students all day,” said Insiya Abdurraheem, one of the therapists currently working with Mana Maali. She’s assigned to a cohort of students whom she reaches out to through the Lantern app, helping them manage their anxiety levels. “The stress they face is a very systemic issue. Only a small percent of the Indian population is in college, and they face a lot of pressure because they’re seen as the hope for the whole country. It’s not an exam, it’s like a war. And they need to perform.”

Mana Maali’s researchers will know whether the program successfully improved student mental health when they analyse the study later this year. If it worked, they plan to expand to more institutes: BITS has expressed interest for its other branches, as has the National Institute for Mental Health and Neurosciences in Bangalore.

The pilot run was financed in part by private donations, but if Mana Maali takes off, colleges will need to pay. Kanuri argues that it will be far cheaper than hiring full-time therapists. On a broader level, she says colleges may need to change their system of education to put more emphasis on personal growth and be more accommodating of students who can’t “slog,” as Rohan put it.

Imran has been talking to his Mana Maali-assigned therapist nearly every day. The pain of losing Akash has yet to ebb, although he does feel better on some days. He wants to move far away from Hyderabad, perhaps to Florida, which has always been a source of fascination. But as school ended this month, his main priority is qualifying for a job in August.

“I just really want to get placed,” he said. “Maybe that’ll help me. I just need to get out.”

Names of the students have been changed to protect their identities.