Paradoxically, in spite of this purported glut of agricultural land at home, Indians are major buyers of farms abroad, mainly in Africa.

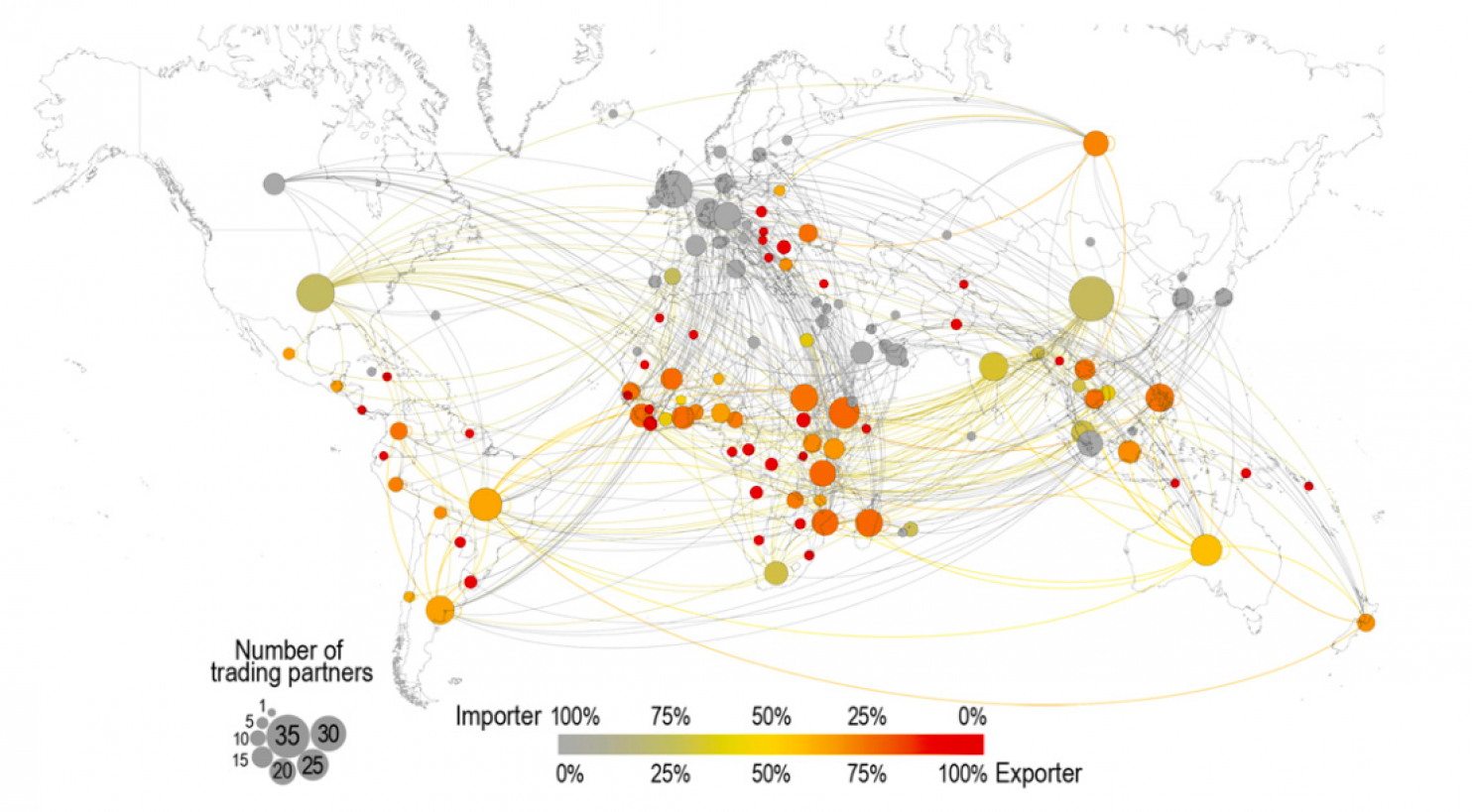

A map created by researchers at Lund University in Sweden shows which countries are buying or leasing land in other nations. The grey end of the scale represents an “importer” or a country buying land in another nation, while its red end represents an “exporter” of land or a country selling its land to foreign buyers. The size of the bubble represents the number of nations a country is trading with.

India figures prominently on the import end of the scale.

Map of the land trading network. Source: Architecture of the global land acquisition system: applying the tools of network science to identify key vulnerabilities.

As expected, Africa is dotted with red and orange bubbles, given that it has been selling and leasing large amounts of its land. The largest bubble figures on the eastern African nation of Ethiopia, where both China and India have been actively buying up land. Brazil and Australia too have large orange bubbles. But unlike Africa, they aren’t selling land due to poverty, but because they have large swathes of land that their small populations aren’t using.

Most of the grey bubbles are – again expectedly – over the developed countries of Europe and the United States, with a particularly large one over Singapore. China has the largest bubble on the map, which means it has the most trading partners. India’s green bubble – meaning it buys land – is one of the biggest on the map.

Here’s a graphic listing the top 20 land-trading countries in the world. Grey bars represent the number of “import” partners and red represent the number of “export” partners. China, as it shows, has bought land in 33 countries while only three countries have bought land in China.

The top 20 countries in the global land trade network, ordered by the largest number of trading partners. The list is also partitioned by number of import partners (grey bars) and number of export partners (red bars). Source: Architecture of the global land acquisition system: applying the tools of network science to identify key vulnerabilities.

India comes in seventh amongst the land importers, tied with Saudi Arabia, which seems to be putting its oil wealth to good use in this case.

Where are Indians buying land?

Almost exclusively in Africa. According to this report in the Economic Times, more than 80 Indian companies have invested about Rs 11,300 crore in purchasing land in countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Senegal and Mozambique.

Who is buying land and why?

The buyers are largely agricultural companies with the odd mineral company here and there. The largest purchaser is Karuturi Global, which is one of the world’s major producers of cut roses. It now owns one of the world’s largest private land banks with 350,000 hectares across Africa, where it intends to cultivate sugarcane, palm oil, rice and vegetables.

Acquisitions are driven by inexpensiveness of land in the continent and authoritarian governments that ensure that Indian companies get large contiguous tracts – a key requirement for large-scale contract farming that these companies are interested in. Rising food prices in India ensure demand for the stuff grown there.

How are Africans reacting to this?

Not too well, actually. According to a report by the US-based Oakland Institute, “the Ethiopian government has committed egregious human rights abuses to make way for agricultural land investments, in direct violation of international law”.

This is, of course, ironic given that for 200 years, India has been at the receiving end of international land grabs.

But why are Indians going abroad at all? Don’t we have surplus agricultural land?

India does have a very large land bank of cultivatable land but a whole range of issues make it unattractive for large-scale private investment.

Indian agricultural land is divided into small parcels which makes it near impossible for companies to use them commercially. Moreover, much of the produce is poor in quality and productivity is very low. Things are so bad that a large number of farmers don’t really turn a profit with their efforts in spite of working all year. Seen purely as a business, it would be unviable but of course since this is a matter of food, agriculture continues even as people trickle away from it, joining the vast, faceless multitudes of urban poor.

Without direct ownership, companies are unwilling to invest in technological improvements to make things better. Moreover, in rural India, contracts are rarely enforced, making it very difficult for a company to transact with a large number of small-holding farmers.

In one way, Indian companies’ investment abroad is really bad news for Indian farmers. It shows that things are so terrible that our companies would go to the trouble of growing food abroad rather than even attempting to fix Indian agriculture.

Is agriculture in India beyond repair then? Are we going to shift to farming abroad?

While Indian agriculture is in dire straits, it’s also a too-big-too-fail industry: it employees around half of India’s workforce. And while Ethiopia might be a great investment for some companies, there is no way we are feeding 1.3 billion Indian from across the Arabian Sea.

India therefore has no choice but to try and pull agriculture out from its crisis.

One way is to basically do in India what’s being done in Africa by Indians and others – large-scale privatisation, bringing in economies of scale and private investment. This will increase productivity and quality, but will, unfortunately, cause so much immediate human displacement and suffering that it’s inconceivable in India’s democracy.

The other is the long hard slog of improving Indian agriculture via farmer education. India was one of the first developing countries to put in place a mass farmer-training programme but has been abysmal at making it work. Take India’s largest crop: rice. Our rice productivity is one of the lowest in the world. Egypt’s productivity is three times ours.

Bangladesh, which also has the problem of small farms, has a rice productivity almost twice of ours. Compared to West Bengal – which has near identical geographical conditions – Bangladesh’s rice productivity is 60% higher.

Interestingly, Bangladesh had similar rice productivity as compared to West Bengal in 1971, its year of independence. But it managed to make improvements through better agriculture interventions – something India hasn’t been able to do well, save in a few pockets such as Punjab and Maharashtra’s sugarcane belt.

How is the Land Acquisition Bill connected to this?

Given that India has so much arable land, Indians buying farms abroad to grow crops is the fever which tells us just how sick Indian agriculture is.

Unfortunately, Narendra Modi as prime minster can do very little about this. A fact he might have omitted while marketing himself as a panacea to all of India’s ills.

Agriculture, including agricultural education, is handled by the states and to improve it, Modi will have to navigate a near impossible maze that will most certainly defeat him. Remember, India’s only major agricultural leap, the Green Revolution, was driven by technology (high-quality seeds), not better administration.

Modi is therefore doing the next best thing he can do: he’s giving up on agriculture completely. The Land Acquisition Bill is Modi telling us that agriculture simply can’t be fixed, so we need to move people from farming to industry.

Unfortunately, this is a bit like putting a Band-Aid on cancer. Industry will simply not be able to absorb a large enough number of ex-farmers, no matter how draconian our land acquisition laws.

For real acche din, we have to reform agriculture. There are no shortcuts.