The study on the Years Lived with Disability at global, regional and national levels for the Global Burden of Disease project found that in India, as in many other parts of the globe, the most time spent in sickness is by those with major depressive disorder. Depression has overtaken anaemia as the leading contributor to YLDs, a broad indicator of public health.

YLD is a method of quantifying extent of a health problem by taking into account the number of cases, the average duration of each case till recovery or death and a certain disease weightage reflecting the severity of the disease. In 2013, major depressive disorder patients together spent more than 9.8 million YLDs, according to the report published by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in the medical journal Lancet. That’s up from less than 6 million YLDs in 1990, a 4% rise when adjusted for ageing.

Depression is a chronic and pervasive condition brought on by biological, psychological or social factors. India’s increase of depressive disorder accompanies an abysmal shortfall in mental health resources. Depression remains under-detected and under-treated across the country. Researchers looking into data from the National Mental Health Resource Survey of 2002 found that India has a 77% average deficit of psychiatrists. More than one-third of India’s population residing in the Hindi heartland, Jammu and Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh has a 90% shortfall of psychiatrists.

This problem is not going away anytime soon. In a paper published last year in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry, researchers found that, “the undergraduate medical curriculum devotes only 1.4% of lecture time and 3.8%-4.1% of internship time to psychiatry, thereby leaving the general practitioners and the non-psychiatrist specialists unprepared to competently deal with mental illness in their practice”. The study said that less than 25% of depression patients receive treatment, the rest falling into the gap between lack of trained mental health personnel and lack of awareness among patients.

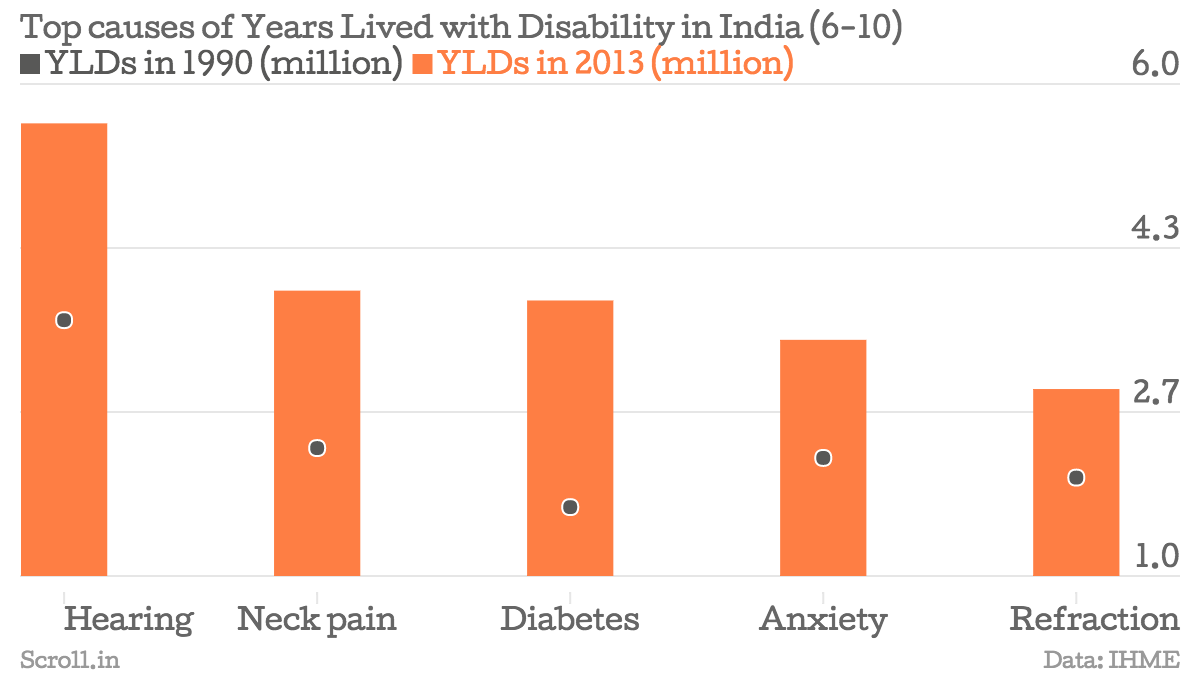

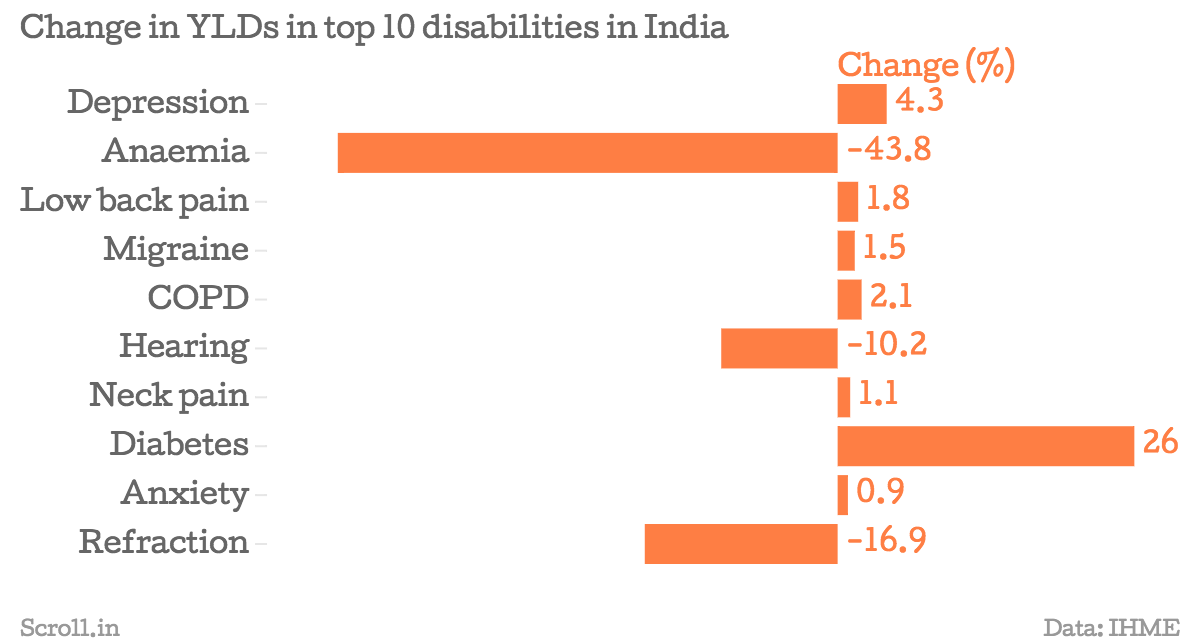

Anxiety is the other psychological disorder that accompanies depression on the list of top causes of YLDs in India. Also making the list are iron-deficiency anaemia, low back pain, migraine, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, loss of hearing, neck pain, diabetes mellitus and uncorrected refractive error in the eye.

The YLDs for each disease, except anaemia, has increased since 1990 in absolute terms. But when corrected for ageing in the population, the YLDs have decreased for hearing loss and refractive error.

The study also showed that the age-standardised change in YLDs for all communicable diseases has declined. There is one stark exception. Dengue has increased almost 400% in age-standardised YLDs since 1990. The findings reiterated other estimates that demonstrate India’s disease transition from infectious to lifestyle diseases. YLDs due to cancer have grown 10% and liver cancer caused by hepatitis C shows a dramatic rise of 121%.

Road injuries and falls are also big contributors to YLDs.

All this calculation of increased years lived with disability shows that India needs to spend more on its ailing population. It provides an indication of how that money might be distributed and also gives a sketch around which the health policy can be decided. India’s healthcare budget is only about 1% of its gross domestic product. In December last year, the government slashed the health budget for the last fiscal by 20% and held the level in the annual budget announcement for 2015-'16.