If it does, the government will be introducing pan-India coverage at a uniform price, at a time when insurance companies, hit hard by higher hospitalisation expenses in leading metros, are increasingly moving away from the concept of ‘one policy, one price’.

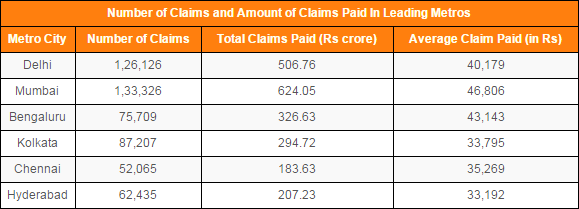

In 2012, claimants in India’s top six cities – 4.5% of India’s population – accounted for 21% of all health insurance claims and received 27% of all health insurance payouts, according to the Insurance Information Bureau of India.

KPMG, a consultancy, estimates that 30 to 40% of all claims come from India’s top six cities, and their average claim size is about 30% higher than the all-India average.

Consider these disparities:

*At Rs 46,806, Mumbai’s average claim size was 497% that of Jharkhand’s Rs 9,403.

*Bengaluru’s average claim of Rs 43,143 was 380% that of Bihar’s Rs 11,340.

As a result, the price of a health cover has become a complex variable, depending on where you live, what hospital you plan to use and your age.

Mumbai, India’s most expensive city for healthcare

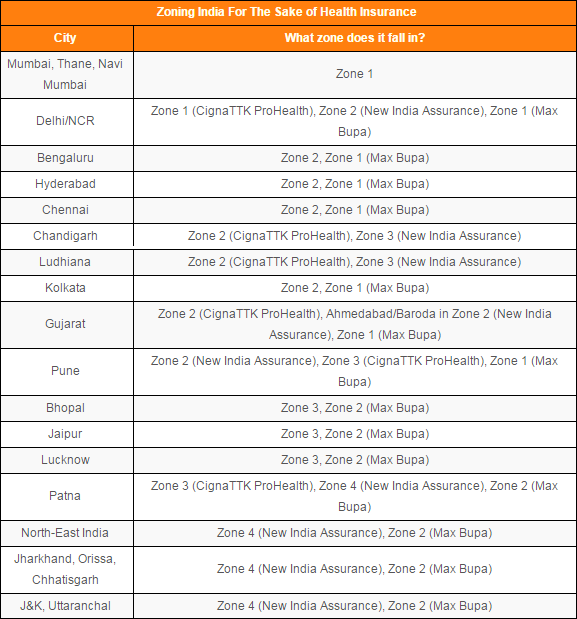

Most insurance companies in India are switching to geographical pricing to address inconsistencies in health-care costs. Geographical pricing ties premiums to the average cost of healthcare in different cities and regions.

“We have demarcated various zones across the country based on the prevailing medical costs and trends in costs,” said Sandeep Patel, managing director & CEO, Cigna TTK Health Insurance, a private health-insurance company.

Zonal premium rates also take cognisance of the existing health infrastructure because tertiary care hospitals in the private sector are fairly expensive, said Patel.

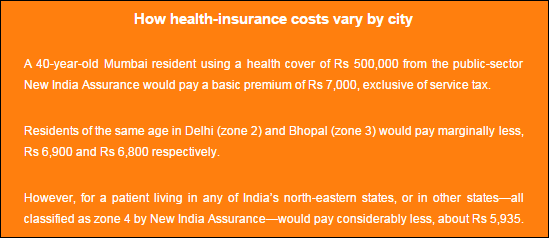

Mumbai is by far India’s most expensive city for healthcare. Its average claim size is 70% higher than the rest of the state of Maharashtra alone.

Source: Insurance Information Bureau of India

Having an angioplasty in Nashik or Pune would set a heart patient back about Rs 2.5 lakh. Undergoing the same procedure in Mumbai (or Delhi) would cost Rs 4 lakh, according to Suresh Sugathan, head, Health Insurance at Bajaj Allianz General Insurance.

Delhi, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Chennai are pricey but several notches below Mumbai.

Source: Insurance Information Bureau of India

Hyderabad, the laggard in the class of six, had an average claim size of Rs 33,192 in 2012, which was lower than Maximum City’s by 41%.

Cities in Gujarat, such as Ahmedabad, Vadodara and Surat, are surprise entries in the list of most expensive places to get healthcare, zone 1, as it is called. Gujarat also made the second-highest number of claims of all states in 2012.

Providers classify the rest of India based on their experience. For instance, CignaTTK classifies Chandigarh and Ludhiana in zone 2, while public-sector provider, New India Assurance Company, puts these cities in zone 3.

Source: Health insurance companies

Small town India enjoys lower healthcare costs and hence, discounts on premiums

Premium rates vary from 7% to 20% between zones for covers from private companies and from 2% to 15% for policies from public companies.

As an example, Max Bupa has defined two zones and introduced tiered pricing based on where customers live and where they opt to get treated.

“Customers living in zone 2 typically get 10% discount on the premium,” said Somesh Chandra, chief operations officer and chief quality officer, Max Bupa Health Insurance. “Additionally, opting to get treated in their hometown or another zone 2 city fetches them a further discount of about 10%.”

But patients who pay a lower premium but get treated in a more expensive zone, for whatever reason—better doctor, only option, advanced medical technology – will be reimbursed only a proportion of the cost of treatment.

Pricing by category: the future of health insurance in India

Zone-based health insurance pricing is fair to people living in smaller cities.

“Zone-based pricing ensures that customers in Tier II/Tier III cities do not cross-subsidise customers in Tier I city by paying the same premium,” said Patel.

Keeping premiums lower in smaller cities also helps push purchases of health insurance in those areas, which Patel said have a very low penetration vis-à-vis metros.

As importantly, differential pricing is vital for the health of the insurance business itself. It helps maintain uniformity in the claims ratio—a measure of the claims incurred and the earned premium – across regions.

Claims ratio is a key indicator of the wellbeing of insurance business – the higher the claims ratio, the less profitable is the insurance business.

It hasn’t been faring too well lately.

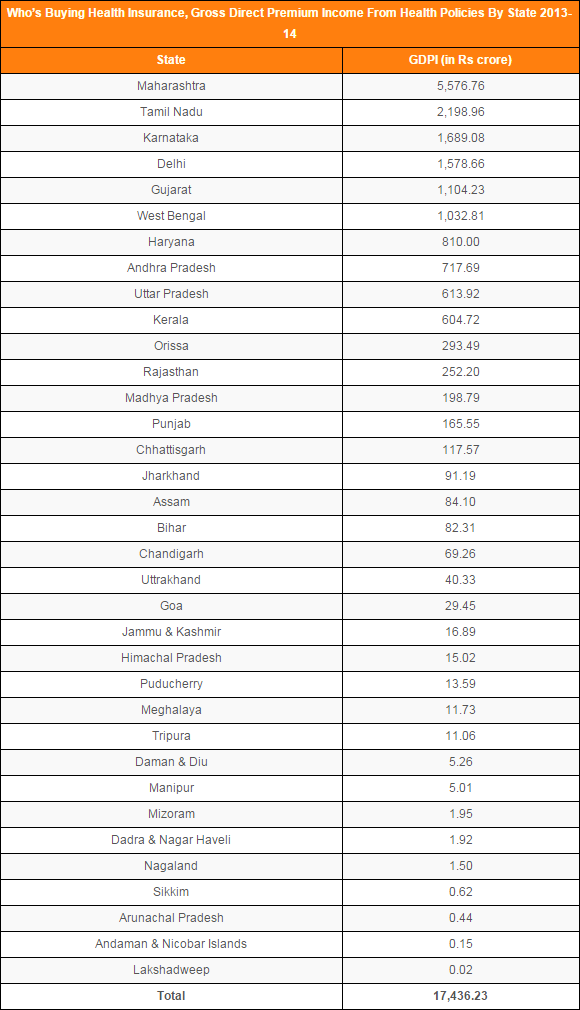

Net Incurred Claims ratio exceeded 90% for every year between 2006 and 2013, despite the Gross Direct Premium Income growing from Rs 3,331 crore to Rs 17,799 crore.

Source: General Insurance Council

So, expect the trend toward geographical pricing to pick up, and intensify.

“I expect the pricing differential to grow to reflect the significant disparity between the cost of health care in leading cities and the rest of India,” said Shashwat Sharma, partner, Management Consulting, KPMG in India.

Some contend that corporate hospital chains may make inroads in smaller cities, pushing up health costs in those places. Even if this happens, metros will see the influx of higher-priced advanced medical technologies, as well as relatively higher inflation, which will preserve or even strengthen the price differential.

To increase the penetration of health insurance in cities, Sharma also expects insurers to take cognizance of the variation in cost of healthcare between corporate hospitals and smaller hospitals, including those run by charitable trusts, and nursing homes.

“The cost of health insurance must fall for huge numbers of low-income customers in metro cities to be brought into the health-insurance net,” said Sharma. “One way of achieving this is to offer policies for different classes of hospital, based on the understanding that economically less privileged people would be willing to get treated in a less expensive government or trust hospital or nursing home.”

This is where government sponsored health-insurance enters the picture. Those covers are likely to restrict treatment to public hospitals in cities. These hospitals are seriously overloaded with patients. Potential partner hospitals of the government, low-cost institutions run by trusts, are likely to face limitations on account of restricted diagnostic facilities, fewer beds and less experienced doctors.

“While the government proposes to gradually increase health spending to 2.5% of the GDP, from 1% currently, it is primarily looking at universal health coverage through strengthening the primary health care network,” said Dr Shaktivel Selvaraj, head of Health Economics and Policy, Public Health Foundation of India.

In other words, the government is hoping to nip disease in the bud and thereby minimise the need for hospitalisation, and hence, secondary healthcare and tertiary health services.

That may be of limited consolation for those buying universal health-insurance policies.

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend.com, a data-driven and public-interest journalism non-profit.