All this has to do with the amusing Indian concept of nazar battu, its main purpose being to protect beauty from the jealous “evil eye”. The nazar battu can be lemons and chillies strung together above the door of someone’s home, an ashy smear strategically applied on a bride’s skin and then hidden away in the folds of her sari, or even a black thread tied around a woman’s toe or ankle.

The irony, however, is that no attempt is made to shield or hide the object of envy from that perceived, ever-lurking evil eye. A bride will never be allowed to look less than perfect, and who dare advise the owner of the new car to keep his precious booty hidden in the garage? No, beauty and wealth must by all means be flaunted, with the protective role entrusted to a token, sometimes microscopic, nazar battu.

To sum up the Indian relationship with beauty and the sense of sight: “dekho magar pyaar se” (look, but with love).

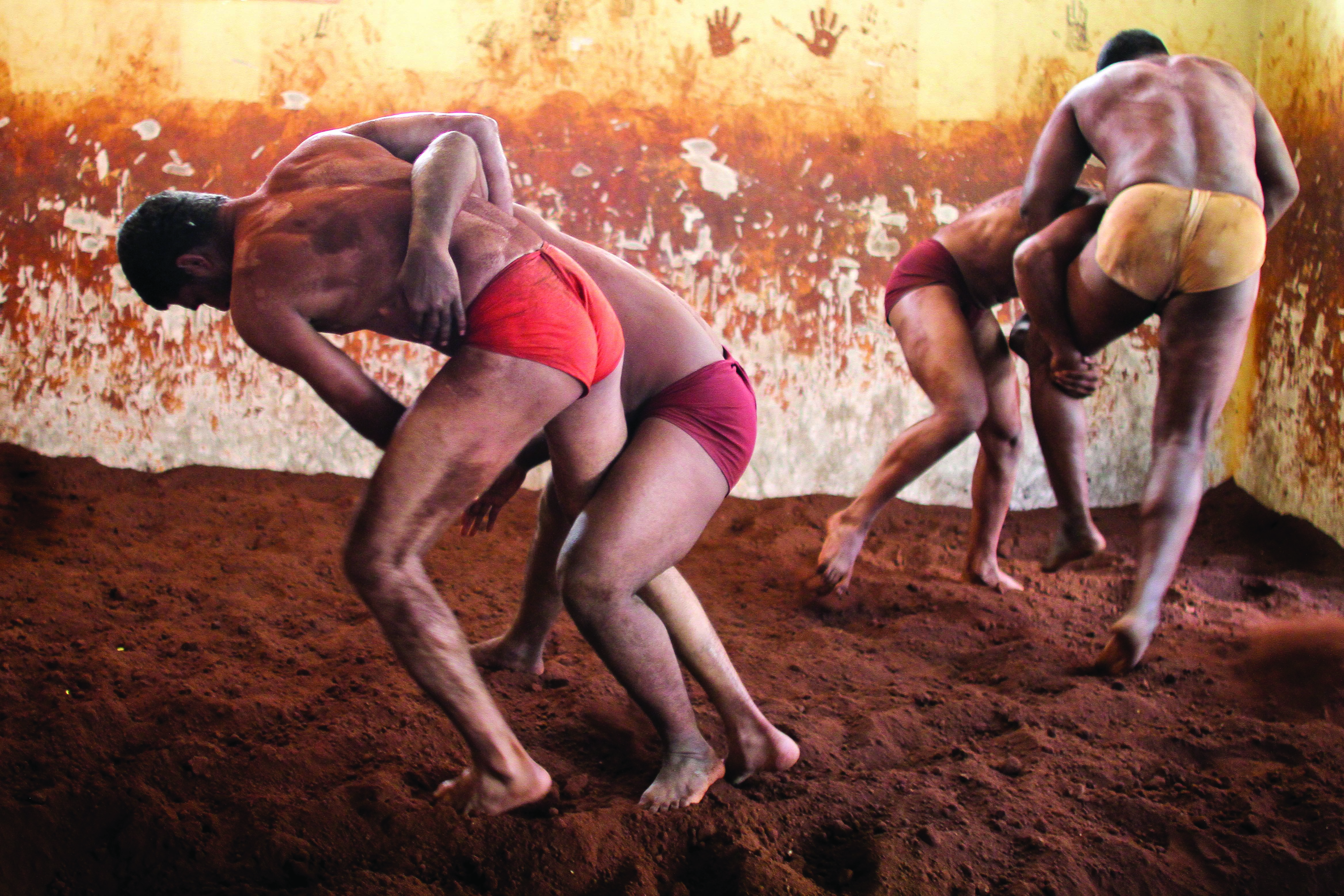

Photograph: Rizwan Mithawala

Photograph: Roli Collection

Photograph: Srinivasa Prasath

Sights, visuals, and appearances provide an all-encompassing glimpse into not just the tangible but also subtle elements of a culture. Hence they have always been of critical importance to India.

Not to be outdone by the sheer beauty of their land, the people of India, it would seem, chose to stay in step. The proof? Beauty treatments and make-up techniques were given the pride of place in ayurveda – an ancient Vedic system of traditional medicine – with thousands of prescribed beauty rituals and remedies juxtaposed against its more “serious” medical concerns such as surgery and preventive medicine.

Ayurveda has listed scores of treatments: lotions, potions, and unguents focused on restoring health and enhancing beauty. Ayurvedic cosmetics – organic and all-natural – could be derived from the ingredients in one’s kitchen.

Sandalwood paste, a beauty aid used even today, played the dual role of protecting the skin from the sun along with enhancing the skin’s glow. Turmeric, saffron, and henna were commonly used to improve the hair texture, colour, and also complexion. In fact, literature of the fifth century AD – for example, Kalidasa’s Shakuntala – lists various ayurvedic beauty treatments favoured by the eponymous seductress.

Even back then, Indians gave much importance to appealing to the observer’s sense of sight. Today, the power of ayurvedic beauty treatments is being acknowledged and many international cosmetic companies are substituting their chemical additives with ayurvedic basics.

The fact that beauty treatments had takers even in ancient India goes to show that the people of this country have never taken beauty (physical or temporal) lightly. The quest for beauty is woven in the country’s cultural fabric, often translating into a feast for the sense of sight.

Photograph: Rizwan Mithawala

Photograph: Soumya Shankar Ghoshal

Photograph: Subrata Biswas

In the sumptuous buffet that India lays out for the eyes, colours mysteriously take on different hues. A simple blue will look exceptionally vivid and acquire the name “phiroza”; orange will pop with drama and turn into “narangi”; a pink will grow richer, deeper and will be referred to as “rani pink”.

There are no scientific reasons to back the claim that colours acquire an altogether different vibrancy in India. Perhaps this belief has something to do with the manner in which colours are linked with emotion. In a country as diverse and divided, it is this very link which speaks volumes and bridges the invisible barriers between people.

Here, colour is just the visual manifestation of a feeling, a feeling so warm that it overrides the differences between the country’s umpteen traditions, outlooks, and ways of living, forming a rainbow-bridge between the realities of over a billion people.

Take, for instance, the colour red. It is not just the colour associated with certain goddesses, it is also the colour of union, sensuality, fertility, and prosperity – which explains why most Indian brides across the country wear red, irrespective of their religion, region, caste, or economic status. Red sindoor and red bangles are also worn by many married women for the same reasons.

Black represents negativity, “evil”, and cunning. Folklore often depicts the witch and the pisach covered head-to-toe in black. White, or the absence of colour, is symbolic of a certain emptiness and is generally worn during funerals and sombre occasions. Traditionally, widows in many parts of India have worn white as a marker of their loss. However, in Kerala, the festival of onam witnesses women wearing white saris with gold borders (also known as the settu sari), as these colours are considered auspicious in the state. The Indian yellow, or turmeric, symbolises sanctity and hope, and is used in Hindu religious rituals and festivals. Green, a favourite among Hindus and Muslims alike, represents nature.

The festival of Diwali is marked by the vibrant yellow of the marigold flowers used to decorate homes; basant panchami – which marks the worship of goddess Saraswati – is a day when believers prefer to wear yellow. Baisakhi is when sikh men add to the festive mood by donning red or pink turbans, as these are the colours of joy and merriment.

Photograph: Vivek Nigam

Photograph: Ayan Ghosh

Photograph: Chetan Soni

In this melting pot of a country, it is not hard to indulge one’s sense of sight. The land is rendered picturesque by the little pretty things like jasmine flowers in a young girl’s hair, or not so pretty – like the oil rainbows that shimmer on the surface of pothole puddles.

India, to those who really look, is an endless array of dizzying, and sometimes chaotic, sights – from the mighty Himalayas up north, to the miles upon miles of lush green ghats, and the striking yellow of the arid Thar desert; from the street walls plastered with juxtaposing images of religious deities and political figures to the unfortunately graffitied monuments; from the hoardings of film posters and adverts dotting the skyline to the tricoloured kites that soar during the Independence day celebrations; from Besant Nagar beach mornings filled with morning walkers, to Alappuzha evenings where the moon plays hide and seek with the swaying coconut trees; from the red-bordered saris of Kolkata to the vibrant Kashmiri phirans; from the traditional Vastu Shastra homes complete with an angan and courtyard to the cramped new-age high-rise apartments.

Though India is not without its fair share of squalor, those who truly know the country will tell you that it is all about finding the beauty in the unsightly, for what you see depends largely on how you perceive it. So, you could curse the aggravating traffic jam of honking cars on New Delhi’s Ring Road, or you could keep yourself amused with the humorous messages painted behind those cargo trucks and three wheelers that might just read, “Dekho, magar pyaar se”.

Look, but with love.

Photograph: Fred Canonge

Photograph: Diganta Gogoi

Photograph: Jakkam N Jegannathaan

Excerpted with permission from India Five Senses, text by Rayman Gill Rai, Concept, Design and Photo-editing by Sneha Pamneja, Lustre Press/Roli Books