As a star athlete and skillful actor, Norman Pritchard was intimately aware of the vagaries of fame. “There is nothing to the fame that blazes one’s name aloft in electric letters overnight,” he said. “One is quite apt to awaken one day and find that the electric letters spell failure where they once spelled success.”

Both success and failure had courted him at different times. In 1900, he became the first British Indian or Indian, depending on who you ask, to win an Olympic medal, only to have his sporting career killed by an injury. A few years later, he became an actor, making a name for himself in photoplays and early silent films. But accusations of domestic violence took the sheen off his star.

By the end of his short life, the proscenium as well as the podium seemed distant from his reality. Mental health troubles left him delusional and led to his confinement in a California sanatorium. They were eventually cited as the cause of his early death in October 1929.

Sporting mark

Pritchard was born in Calcutta in either 1875 or 1877, depending on the record you consult. His father, George, an Englishman born in Bengal, was a trader of tea, indigo and jute, and Pritchard spent his early years on a mountainous tea plantation that was “a nine day’s donkey’s ride away from Calcutta”, as per The New York Times.

Pritchard made his first sporting mark in 1893 when he swept the Bengal Presidency Association championships, a feat he repeated over the next seven years, earning the moniker “Calcutta flier”.

Between 1893 and 1900, the young man set various records in track and field events in Bombay Presidency and Bengal Presidency, running the 100 yards in approximately 10 seconds, 110 yards in 15 seconds, and 440 yards in 50 seconds. The Daily Mirror reported in 1912 that he held a record for walking a mile, running a mile and then riding on horseback in 18 minutes 22 seconds.

In June 1900, when he arrived in England for the Amateur Athletic Championships, an Australian newspaper, The Referee, referred to him as “India’s star athlete”. He lived up to the label at the 1900 Paris Olympics, bagging silver medals in two events.

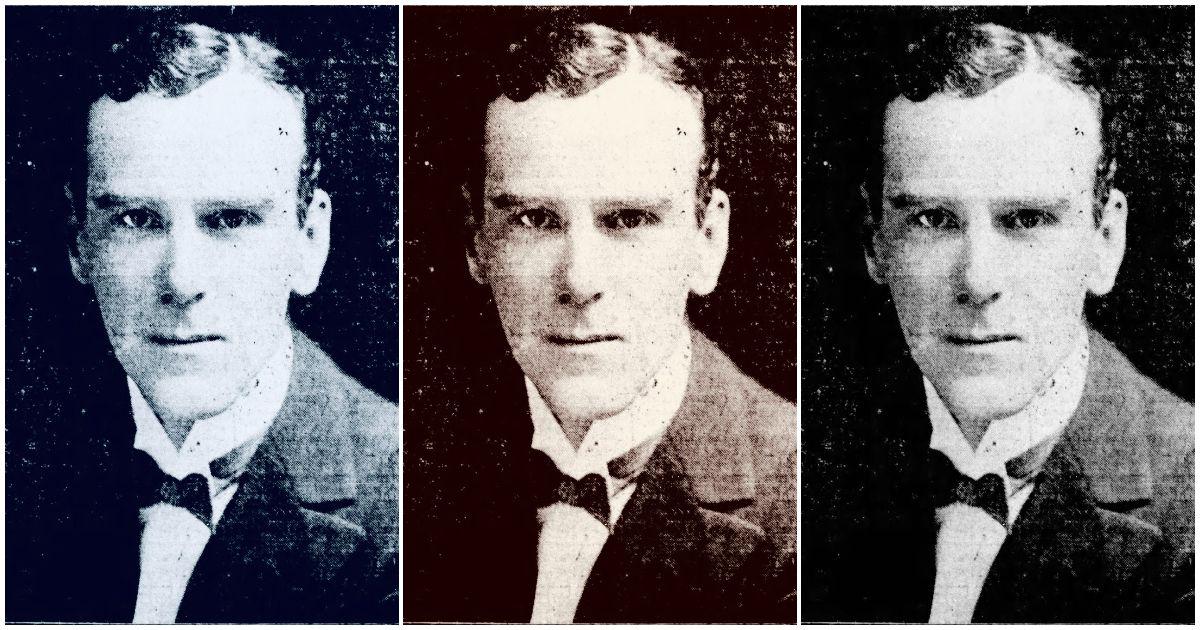

![Norman Pritchard. Credit: The Sketch/Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain].](https://sc0.blr1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/inline/hjdncmyyts-1741328886.png)

His first silver came in the 200m race, which the American William Tewksbury ran in 22.2 seconds, 0.6 seconds faster than Pritchard’s 22.8. And his second silver came in 200m hurdles, in which he was pipped by the American star athlete Alvin Kraenzlein by – again – 0.6 seconds.

What Pritchard achieved in Paris he could never replicate again. A serious leg injury in 1907 ended his sporting career, although the Bengal Presidency Association was keen that he train for the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. By this time, he was beguiled by something else: the lure of the stage.

Different turn

Pritchard had moved to England with his family in 1905 and started trading, like his father, in tea, indigo and jute. His 10-year marriage to Constance Clague, with whom he had a daughter, was on the verge of collapse. A swirl of controversy had enveloped him. A probate court petition filed by his wife in England in April 1906 accused him of assaulting her on several occasions.

Amid these circumstances, Pritchard’s life took a different turn. In December 1906, he was at a dinner in London, narrating events of the Delhi Durbar of 1903, which commemorated the coronation of King Edward VII, and among his audience was the celebrated actor-manager Sir Charles Wyndham. Wyndham liked what he saw and offered Pritchard a bit role in his play The Stronger Sex.

At first Pritchard was noncommittal. He changed his mind after getting advice from another producer, Sir George Alexander. Alexander himself had given Pritchard a footman’s role in his play, Sir John Glayde’s Honour, and made him the understudy for all the male roles. Alexander’s counsel was that Pritchard take acting seriously.

Within three months, Pritchard’s fortunes changed as fortuity elevated him to lead actor status. One instance where luck intervened on his behalf was when the actor-manager Herbert Druce’s chosen lead for the play Pocket Miss Hercules recommended Pritchard.

Pritchard, under the screen name Norman Trevor, did not squander the opportunity he had been given. Over the next seven years, he became fairly well-known for his theatre work. In 1909, he toured England with his own company, performing modern and Shakespearean plays. And in 1913, he became an actor-manager, producing and starring in several plays at the Savoy, including The Cardinal’s Romance and The Seven Sisters.

This was a period of regular unrest on the global stage. Italy had invaded Libya in 1911, the Balkan Wars began in 1912, and the First World War was just around the corner. When the Great War did break out, Pritchard could not enlist because of his injury. So instead he accepted producer William Brady’s contract to perform in New York and debuted on Broadway with The Elder Son in September 1914.

One of Pritchard’s popular performances was in A Kiss For Cinderella (1916), a play by James Barrie, who is more popular as the writer of Peter Pan. The two worked together several times, prompting an appreciator to call Pritchard “a delightful actor of Barrie parts”.

While working in theatre, Pritchard did some photoplays. His first photoplays, both produced by William Brady, were staged in 1915: the makers photographed staged places, mounted the film on reel, and screened them in theatres. In 1917, he helped raise funds for the war at a rally in New York and spoke on the war’s impact on the theatre.

About him, The Sun said on November 25, 1917:

“His broad experience of life before he came to the States has given him a rare power of intelligent understanding and interpretation of varied types, which added to his art as an actor makes his performances always of special interest.”

Pritchard’s dedication to his art was impressive. One evening, despite suffering from a chill, he turned up to perform and had to be sustained with doses of oxygen. But the famed critic Dorothy Parker saw it differently:

“…he had committed to memory a total of perhaps eight lines for the three acts, and, for the remainder of his part, recited aloud the whispered words supplied by his earnest coworkers. It was considerate, in that it gave those seated down front the opportunity to hear each of his speeches twice over, but it tended to retard the action a trifle.”

Seasoned actor

In all, Pritchard performed 29 roles on Broadway between 1914 and 1926. Interspersed with these were occasional jobs in films, including in the silent film Jane Eyre (1921). In 1926, he plunged headlong into the world of movies and moved to California.

As the era of talkies advanced, the critic Eugene Segal wrote that Pritchard was poised to make a successful transition from a silent movie actor: “His peculiar qualifications may rest in his eyes. Then he is given to restraint in action and a very flexible upper portion of the face tells the story.” This was not to be.

By the late 1920s, Pritchard’s downward spiral had begun. He was arrested in 1928 when his cheques bounced and had to be rescued by his friend, fellow actor HB Warner. Warner said that Pritchard had become delusional, believing that he was a rich man, when in truth, he had little money left in the bank.

The California State Lunacy Commission committed Pritchard to a sanatorium. Among his last films were Tonight at Twelve, The Love Trap and Mad Hour, in which he played Ernest Hemingway. Recommitted to a sanatorium in the fall of 1929, Pritchard died on October 30 from “a nervous condition of the brain”. He was in his early 50s.

Parker called Pritchard “a likable and seasoned actor”, but more fulsome praise came from the columnist Gladys Hall of the Windsor Star in Canada. In her Diary of a Movie Fan, she described Pritchard as a man every woman fell in love with sooner or later.