Photos: Families of Kashmiris killed by armed forces aren't sure they'll ever find justice

It's 25 years since the Armed Forces Special Powers (Jammu and Kashmir) Act was imposed on the state.

The armed forces draw immunity specifically from section 7 of AFSPA, which stipulates that prior permission from the state or central authorities is required to prosecute the alleged perpetrators in civil courts. After charges are framed by the police, the case file must be sent to the Ministry of Defence or the Ministry of Home Affairs for permission to prosecute.

This permission is rarely ever granted. Here are a few cases highlighted by Amnesty International where young men were allegedly killed by the armed forces and their families are enduring an endless wait for justice.

Name: Irfan Ahmad Ganai

Age: 17

Killed in June 2013

Residence: Markundal village, Ganderbal district

Status of sanction: Not sought. Investigation still in progress

Irfan Ahmad Ganai’s family continues to fight for justice, running from police station to court hoping to get the guilty punished for the death of their 17-year-old boy.

Irfan Ahmad Ganai was sleeping at his cousin’s house on the night of June 30, 2013, in Markundal village, when he and his older cousin, Reyaz, woke to the sound of gunshots outside the house. There had been a series of livestock thefts in recent weeks, so they went outside to investigate.

“Irfan went a few steps ahead of me,” Reyaz recounted. “We didn’t see the army personnel that surrounded the house. Nobody’s lights were on, so we couldn’t see.” Suddenly, Reyaz heard a gunshot and saw Irfan collapse in front of him, blood seeping through his shirt where the bullet had hit him. He was dead when he hit the ground.

The police at Sumbal police station in Ganderbal District registered a First Information Report against unidentified army personnel in a case of murder on June 30, 2013.

On August 7, 2013, the Sub-Divisional Police Officer, Sumbal, addressed a letter to the District Superintendent of Police, Bandipora, informing him that the Sumbal police station had sent letters to the Commanding Officer of the 13 Rashtriya Rifles on July 2, July 16 and August 3, requesting the list of army personnel who participated in the operation on June 30, 2013, in Markundal, the types of weapon carried by each soldier, details of vehicles used in the operation, and the details of drivers, both civilian and army. He reported that “the army authorities till date [August 7, 2013] have not furnished any information as was requested… which has hampered the investigation of the case”.

On August 9, 2013, the 13 Rashtriya Rifles finally wrote to the District Superintendent saying that they had “approached the higher headquarters for sharing the details” and assured “full cooperation” from the army’s side. However, no information was shared. On September 27, 2013, the Sub-Divisional Police Officer sent another reminder to the Commanding Officer of the 13 Rashtriya Rifles stating that the requested information had still not been provided. To date, the army has failed to respond to the police’s request for information.

On October 5, 2013, the police filed charges against a civilian, Manzoor Ahmad Sheikh, for murder and conspiracy to murder in the case. Sheikh, who is currently on trial, worked as an informer for the 13 Rashtriya Rifles, and had accompanied the army to Markundal during the operation when Irfan Ganai was killed.

A legal officer closely involved in the prosecution agreed to speak with Amnesty International India on the condition of anonymity in July 2014. He said the police ceased their investigations into army involvement in Irfan Ganai’s shooting once the army refused to provide information. He said that the police would file charges against army personnel if “further evidence against the army comes to light”. He said that no army officers or personnel had testified during police investigations or court proceedings to date, despite being summoned by the police.

Name: Javaid Ahmad Magray

Age: 17

Killed in April 2003

Residence: Budgam district

Status of Sanction: Sought, denied by the Ministry of Defence

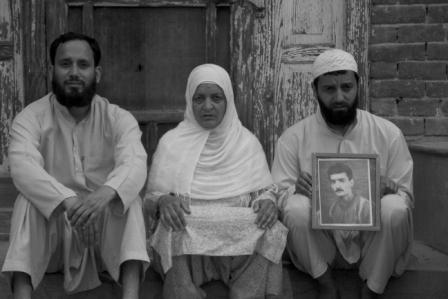

'AFSPA is a like a blank cheque from the government to kill innocents like my son. He was only 17 years old,' says Javaid’s father Ghulam Nabi Magray (right).

Javaid Ahmad Magray was studying in his room when his family saw him alive for the last time. It was late on April 30, 2003. The next morning, Javaid was gone.

His father Ghulam Nabi Magray saw a few army personnel standing at the gate outside, and told them that his son was missing. They said, “Don’t look for him, and go back inside.” But down the road, Ghulam Nabi and his wife Fatima Begum could see bloodstains and a tooth lying on the pavement.

During the investigations that followed, Ghulam Nabi testified that the officer in charge of the army camp at Soiteng had told them that Javaid was in the Nowgam police station. The family had rushed to the police station, only to be told that Javaid had been brought there at about 3 am. He was then taken to Barzalla Hospital, then shifted to SMSH Hospital, and finally to Soura Medical Institute, where he was declared dead.

An officer at Soiteng testified during investigations that Javaid had been wounded in an encounter with some security force personnel, and was taken to Nowgam police station and later to a hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries.

The chief [Station House] officer of Nowgam police station testified that the same officer of the Assam Regiment, “on May 1 2003 at 2:30 am came with a written application that their party was on patrolling of the area and at 00:30 hours [one militant was wounded] while three others taking the benefit of heavy rains and darkness succeeded in running away.”

The police registered a First Information Report and sent Javaid to the hospital. They also testified that the police station had no record that Javaid was involved in “anti-national activity or militancy.”

Relatives and neighbours of Javaid, his teachers, and representatives of the army and the police took part in the inquiry into his death carried out by the district magistrate. The report concluded that the army’s version of events was false, and that the “deceased boy was not a militant… and has been killed without any justification by a Subedar [a junior commissioned officer in the Indian Army] and his army men being the head of the patrolling party”.

According to the district magistrate’s report, the Subedar left Srinagar and failed to respond to official summons to record his statement for the investigation. The army, in a letter to the magistrate, said that the Subedar’s unit had been moved and suggested that further correspondence should be sent to another army address. A subsequent letter sent was returned undelivered after 16 days.

In a letter dated July 16, 2007, the Jammu and Kashmir Home Department wrote to the Joint Secretary (K-1), Ministry of Defence in Delhi to seek sanction to prosecute nine army personnel against whom the state police had filed charges of murder and conspiracy to murder for Javaid’s death. The letter stated that “the deceased was a student and was not linked with militancy. He was killed by Assam Regiment after kidnapping. The case registered by the Assam Regiment against the deceased [as a “militant from whom arms and ammunition was recovered”] has been closed as not proved”. The letter requested the Ministry of Defence to “kindly accord sanction of prosecution as is envisaged under section 7 of the Jammu and Kashmir Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1990 against the accused Army officials”.

Ghulam Nabi knows that the case was sent for sanction – or official permission to prosecute the security force personnel – under the AFSPA in 2007 but says he has received no information on the outcome of the application. “We simply never heard what happened with it,” he told Amnesty International India.

A Ministry of Defence document dated January 10, 2012, simply states that sanction for prosecution was denied on the grounds that “the individual killed was a militant from whom arms and ammunition was recovered. No reliable and tangible evidence has been referred to in the investigation report”.

Sanction to prosecute is recorded as having been denied on January 3, 2011, three and a half years after it was sought by the Jammu and Kashmir authorities. Ghulam Nabi and his family were never officially informed about it.

“The problem is that the army never accepts that sometimes these violations happen. They’re always in denial,” Ghulam Nabi said.

Name: Ashiq Hussain Ganai

Age: 24

Killed in April 1993

Residence: Dangiwacha village, Baramulla

Status of Sanction: Sought, Declined by the Ministry of Defence

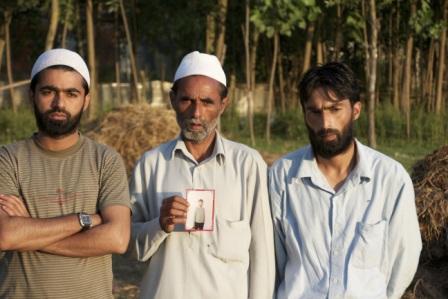

Like Ashiq’s father, his brothers have vowed to fight for justice till their last breath.

Ashiq Hussain Ganai was allegedly tortured and killed by the army in 1993. His decomposed and mutilated body was found by the Jammu and Kashmir Police on the banks of the River Jhelum on April 12, 1993, 40 days after the army picked him up from his home.

The Ministry of Defence denied sanction to prosecute in 1997 without providing any reasons for their denial. On May 14, 1999, the family filed a writ petition before the Jammu and Kashmir High Court challenging the denial of sanction to prosecute the two army personnel identified by the police investigation. Multiple court adjournments followed, and the Jammu and Kashmir High Court granted further time to the central government to respond. The most recent court order available is dated November 20, 2006, in which the High Court granted further time to the Union of India to submit a response to the challenge. No further action is known to have been taken.

Ashiq’s brother Imtiyaz Rasool Hussain said: “Initially, the army denied Ashiq’s arrest. My father Ghulam Rasool Ganai was later assured by a senior army officer stationed at Baramulla that Ashiq would be released on March 23, 1993. On March 21, 1993, two majors responsible for Ashiq’s arrest raided our house. They took my father and my younger brother Nisar Ahmed away. The army wanted my father to sign blank papers but he refused. Next day, we were told that Ashiq’s custody was transferred to the 79 Battalion of the army and he would be released on March 25. But a few days later his body was found in the Jhelum River.”

Ashiq’s brother other brother Naseer Ahmad added: “Our case is currently in the High Court and sanction from the Ministry of Home Affairs is still pending. It was common here, in those days, for the army to pick up boys and men, even torturing them. But my brother was a student. There were always misunderstandings at that time.”

He continued: “We faced many threats from the army. My father was arrested many times, tortured and he had to flee from the village. The army used many tactics to threaten us, but my father did not yield. He told the Superintendent of Police in Baramulla District, and the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir ordered the police to provide us protection. That is why this police station at Dangiwacha, in our village, is now here. This police station was not here prior to the court ordered protection for us…but there is nothing happening in this case.”

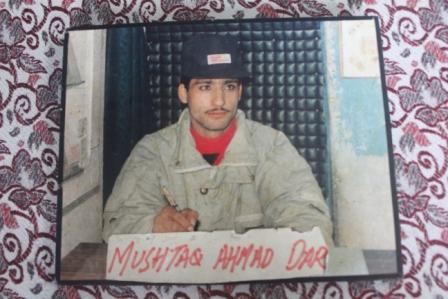

Name: Mushtaq Ahmad Dar

Age: 25

Disappeared in April 1997

Residence: Srinagar

Status of Sanction: Sought. Pending with Ministry of Defence

Mushtaq was the lone breadwinner for his family of six when he was abducted by the army in 1997.

Mushtaq Ahmad Dar was abducted by army personnel in 1997 from his home in Srinagar – his family never saw him again. It took the police 12 years to register a complaint and investigate the enforced disappearance of Mushtaq Ahmad Dar. The army personnel who took him away accused Dar and his friend, who were neighbours, of being informers for armed groups, and harbouring arms and ammunition.

Family members said they attempted to register complaints at multiple police stations in Srinagar the day after the incident. Mushtaq Ahmad Dar’s mother said she approached two police stations, the second of which she believed had registered a complaint, although she did not receive a copy of the written record, as required by Indian law.

After two years of inaction by the police, the family of Mushtaq Ahmad Dar filed a writ petition before the Jammu and Kashmir High Court in 1999, demanding to know his whereabouts, and seeking an enquiry into his disappearance and financial compensation. The Jammu and Kashmir High Court ordered a judicial enquiry on May 2, 2000.

The report of the inquiry, completed on July 18, 2000, stated: “Mustaq Ahmad Dar was lifted by 20 Grenadiers of the Army camped at Boatman Colony Bemina on 13 April 1997 and thereafter disappeared.” Based on the findings of the inquiry, the Court ordered police to register a case and investigate Mushtaq Ahmad Dar’s abduction and subsequent disappearance. Despite the order, there is no record of a case being registered until 2009, more than six years after the court order. The reasons for the delay are unknown.

Investigations into Mushtaq Ahmad Dar’s disappearance were completed in 2012 and the case forwarded to the Ministry of Defence for grant of sanction to prosecute. The case was being considered by the Ministry of Defence as of March 2013. No decision has yet been issued, to the knowledge of the family or their lawyer.

Name: Zahid Farooq Sheikh

Age: 16

Killed in February 2010

Residence: Srinagar

Status of Sanction: Not sought. Case reached the Supreme Court, which then handed it back to the court of the Border Security Force

Zahid Farooq Sheikh's family has fighting for five years to get justice for their son.

Zahid Farooq Sheikh was killed in February 2010 by Border Security Force personnel as he was walking home after playing cricket with friends in Srinagar.

The Supreme Court in its judgement in April 2013 noted that the Commandant of the 68th Battalion of the Force “…accompanied by other Force personnel… got stuck in a traffic jam. This led to a verbal duel with some boys present at Boulevard Road, Brain, Srinagar. The verbal duel took an ugly turn and the Force personnel started chasing the boys. It is alleged that… (a constable) fired twice and one of the rounds hit Zahid Farooq Sheikh. Zahid died of the fire arm injury instantaneously.”

Unlike many past cases of alleged human rights violations, the state police investigation into Zahid’s killing was conducted swiftly, and within a few weeks of the incident, the police filed charges of murder against two BSF personnel. The BSF did not deny that their soldiers were responsible for Zahid’s death, and began conducting security force court proceedings against the accused after the conclusion of the police investigations, arguing that because their personnel are always considered on “active duty” in a state designated as “disturbed”, they were empowered to try their personnel in a military court.

Zahid’s father, Farooq Sheikh, and his family petitioned to have the case tried in a civilian court as they were not convinced they would get justice from the security forces. “We are not told anything when they conduct a trial. We don’t have access to any information,” said Farooq Sheikh. “How will we know that the guilty are even punished? The only way we can be sure is to have the trial in the civil court.”

In March 2013, Farooq Sheikh was called to testify before the BSF Court. Farooq says the BSF summoned him several times through the local police, but he was reluctant to attend the proceedings as they were held at the BSF camp at Panthachowk in Srinagar, which only military personnel are usually allowed to enter. He said he felt nervous about entering the BSF premises, and feared intimidation or harassment.

Farooq said that he and another witness, Mushtaq Wani, who was with Zahid when he was killed, went to testify before the Security Force Court, also in March 2013. The BSF had appointed a lawyer for them, who Farooq says was from Jammu. Farooq said, “They repeatedly tried to discredit Mushtaq. They repeatedly projected the incident as if there was stone-pelting at the time. But the police have made official reports that everything was normal at that time. No stone-pelting was going on… The cross-examination was done by a soldier who questioned Mushtaq and kept accusing him of being a militant, asking him about his activities and whereabouts.”

Farooq told Amnesty International India that he did not trust the BSF court proceedings. At the hearing, Farooq says that there were 14 other witnesses produced by the local police and witnesses from the BSF side. When he went to testify, he says, a senior officer of the unit fell at his feet and said, “Please forgive me, we have made a mistake.” Farooq replied, “How can I forgive you. You have killed an innocent boy.”

Zahid’s cousin Nasir Sheikh added: “They [the BSF] will complete the investigation and trial, they have just one or two more witnesses to depose before the court, and then most probably the accused will be transferred to another place, and we will never know what comes of the case. Just like in the Pathribal case, the BSF are saying that there were no eyewitnesses to the incident so they cannot charge the accused with murder.”

The BSF court proceedings were yet to conclude at the time of writing. Farooq Sheikh said he has not been contacted by BSF authorities since he attended the hearing at Panthachowk in 2013.

Farooq Sheikh and his lawyer, Nazir Ronga, continue to fight for the case to be tried in the civilian court. “The fact that the BSF are fighting so hard to bring the case back into the military court makes me suspicious. What are they trying to hide?” says the lawyer. Having had their appeal to the Supreme Court dismissed once, they applied to the Jammu and Kashmir courts again on the grounds that the BSF did not try their personnel within the time directed by the Supreme Court. However, the Sessions court in Srinagar directed the family to approach the Supreme Court again to seek re-evaluation of its decision in June 2014.