1. Letter to Agatha Harrison, a friend in London

Miss Agatha Harrison

Old Jordan's Hostel

Near Beaconsfield Bucks, S.W. II

My Dear Agatha,

This letter I am dictating whilst I am spinning. You know, my way of celebrating great events, such as today’s, is to thank God for it and, therefore, to pray. This prayer must be accompanied by a fast, if the taking of fruit juices may be so described. And then as a mark of identification with the poor and dedication there must be spinning. Hence I must not be satisfied with the spinning I do every day, but I must do as much as is possible in consistence with my other appointments.

I got through Amrit your first letter at 4 o’clock in the morning. I have through her your second letter. This has been brought by Rajaji, the Governor of West Bengal. Rajaji could not afford to come himself. The Government House is surrounded by a huge admiring crowd. He is, therefore, a prisoner in his own house. He sent his secretary with Rajkumari’s packet.

You refer me to Winterton’s speech, which you will be surprised to learn, I have not read. The speeches during the debate on the Independence Bill, I was not able to read. I rarely get a moment to read newspapers. Some portions are either read to me or I glance during odd moments. What does it matter, who talks in my favour or against me, if I myself am sound at bottom? After all you and I have to do our duty in the best manner we know and keep on smiling. Rest from the papers. I am about to finish my spinning. Therefore I must think of other things.

My love to all our friends. I was glad to find that Carl Heath was well enough to preside at the gathering described by you.

How I wish I could tell you all about the happenings here. Perhaps Horace will. He was with me for a few days. He left me only last night.

Love.

Bapu

2. Letter to Ramendra G. Sinha, who had written to Gandhi about how his father had died while trying to stem the rioting

Ramendra G Sinha

Gopal Mullick Lane, Bowbazar,

Calcutta

Dear Friend,

I must take you at your word. As you say, your father had in him non-violence of the brave. Such a one never dies, destruction of the body has no meaning for him. Therefore, it is not right for you, your mother [or anyone] to mourn over the death of your brave father. He has left, in dying, a rich legacy which I hope you will all deserve. The best advice I can give is that you should all do whatever you can for the building up of the freedom that has come to us today and the first thing you can do is to copy your father’s bravery.

Bravery of non-violence is shown in a variety of ways, not necessarily in dying at the hands of an assassin. There is no doubt that if you earn an honest price for the loss of your dear ones that by itself will be a contribution to the preservation of the dearly earned freedom.

Yours sincerely,

M. K. Gandhi

3. Advice to West Bengal ministers

From today you have to wear the crown of thorns. Strive ceaselessly to cultivate truth and non-violence. Be humble. Be forbearing. The British rule no doubt put you on your mettle. But now you will be tested through and through. Beware of power; power corrupts. Do not let yourselves be entrapped by its pomp and pageantry. Remember, you are in office to serve the poor in India’s villages. May God help you.

4. Talk with C. Rajagopalachari

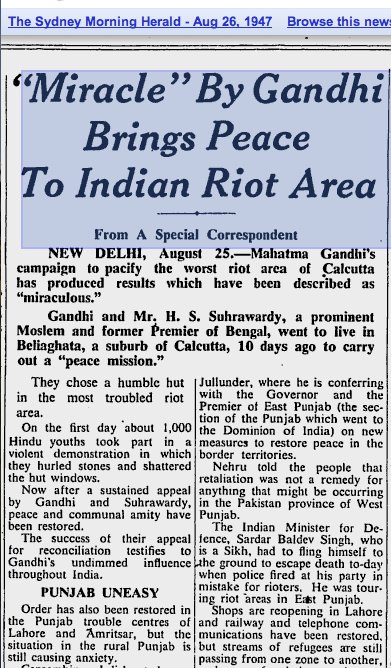

The new Governor of the province, C. Rajagopalachari, paid him a respectful visit and congratulated him on the “miracle which he had wrought” (stemming rioting in Calcutta). But Gandhiji replied that he could not be satisfied until Hindus and Muslims felt safe in one another’s company and returned to their own homes to live as before. Without that change of heart, there was likelihood of future deterioration in spite of the present enthusiasm.

5. Talk with Communist Party members

At 2, there was an interview with some members of the Communist Party of India to whom Gandhiji said that political workers, whether Communist or Socialist, must forget today all differences and help to consolidate the freedom which had been attained. Should we allow it to break into pieces? The tragedy was that the strength with which the country had fought against the British was failing them when it came to the establishment of Hindu-Muslim unity.

With regard to the celebrations, Gandhiji said: I can’t afford to take part in this rejoicing, which is a sorry affair.

6. Talk to students

Gandhiji explained in detail why the fighting must stop now. We had two States now, each of which was to have both Hindu and Muslim citizens. If that were so, it meant an end of the two-nation theory. Students ought to think and think well. They should do no wrong. It was wrong to molest an Indian citizen merely because he professed a different religion. Students should do everything to build up a new State of India which would be everybody’s pride. With regard to the demonstration of fraternisation, he said: I am not lifted off my feet by these demonstrations of joy.

7. Speech at prayer meeting

Gandhiji congratulated Calcutta on Hindus and Muslims meeting together in perfect friendliness. Muslims shouted the same slogans of joy as the Hindus. They flew the tricolour without the slightest hesitation. What was more, the Hindus were admitted to mosques and Muslims were admitted to the Hindu mandirs. This news reminded him of the Khilafat days when Hindus and Muslims fraternised with one another. If this exhibition was from the heart and was not a momentary impulse, it was better than the Khilafat days. The simple reason was that they had both drunk the poison cup of disturbances. The nectar of friendliness should, therefore, taste sweeter than before. He was however sorry to hear that in a certain part the poor Muslims experienced molestation. He hoped that Calcutta including Howrah will be entirely free from the communal virus for ever. Then indeed they need have no fear about East Bengal and the rest of India. He was sorry, therefore, to hear that madness still reged in Lahore. He could hope and feel sure that the noble example of Calcutta, if it was sincere, would affect the Punjab and the other parts of India. He then referred to Chittagong. Rain was no respecter of persons. It engulfed both Muslims and Hindus. It was the duty of the whole of Bengal to feel one with the sufferers of Chittagong.

He then referred to the fact that the people realising that India was free, took possession of the Government House and in affection besieged their new Governor Rajaji. He would be glad if it meant only a token of the people’s power. But he would be sick and sorry if the people thought that they could do what they liked with the Government and other property. That would be criminal lawlessness. He hoped, therefore, that they had of their own accord vacated the Governor’s palace as readily as they had occupied it. He would warn the people that now that they were free, they would use the freedom with wise restraint. They should know that they were to treat the Europeans who stayed in India with the same regard as they would expect for themselves. They must know that they were masters of no one but of themselves. They must not compel anyone to do anything against his will.

From The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.

We welcome your comments at

letters@scroll.in.

Miss Agatha Harrison

Old Jordan's Hostel

Near Beaconsfield Bucks, S.W. II

My Dear Agatha,

This letter I am dictating whilst I am spinning. You know, my way of celebrating great events, such as today’s, is to thank God for it and, therefore, to pray. This prayer must be accompanied by a fast, if the taking of fruit juices may be so described. And then as a mark of identification with the poor and dedication there must be spinning. Hence I must not be satisfied with the spinning I do every day, but I must do as much as is possible in consistence with my other appointments.

I got through Amrit your first letter at 4 o’clock in the morning. I have through her your second letter. This has been brought by Rajaji, the Governor of West Bengal. Rajaji could not afford to come himself. The Government House is surrounded by a huge admiring crowd. He is, therefore, a prisoner in his own house. He sent his secretary with Rajkumari’s packet.

You refer me to Winterton’s speech, which you will be surprised to learn, I have not read. The speeches during the debate on the Independence Bill, I was not able to read. I rarely get a moment to read newspapers. Some portions are either read to me or I glance during odd moments. What does it matter, who talks in my favour or against me, if I myself am sound at bottom? After all you and I have to do our duty in the best manner we know and keep on smiling. Rest from the papers. I am about to finish my spinning. Therefore I must think of other things.

My love to all our friends. I was glad to find that Carl Heath was well enough to preside at the gathering described by you.

How I wish I could tell you all about the happenings here. Perhaps Horace will. He was with me for a few days. He left me only last night.

Love.

Bapu

2. Letter to Ramendra G. Sinha, who had written to Gandhi about how his father had died while trying to stem the rioting

Ramendra G Sinha

Gopal Mullick Lane, Bowbazar,

Calcutta

Dear Friend,

I must take you at your word. As you say, your father had in him non-violence of the brave. Such a one never dies, destruction of the body has no meaning for him. Therefore, it is not right for you, your mother [or anyone] to mourn over the death of your brave father. He has left, in dying, a rich legacy which I hope you will all deserve. The best advice I can give is that you should all do whatever you can for the building up of the freedom that has come to us today and the first thing you can do is to copy your father’s bravery.

Bravery of non-violence is shown in a variety of ways, not necessarily in dying at the hands of an assassin. There is no doubt that if you earn an honest price for the loss of your dear ones that by itself will be a contribution to the preservation of the dearly earned freedom.

Yours sincerely,

M. K. Gandhi

3. Advice to West Bengal ministers

From today you have to wear the crown of thorns. Strive ceaselessly to cultivate truth and non-violence. Be humble. Be forbearing. The British rule no doubt put you on your mettle. But now you will be tested through and through. Beware of power; power corrupts. Do not let yourselves be entrapped by its pomp and pageantry. Remember, you are in office to serve the poor in India’s villages. May God help you.

4. Talk with C. Rajagopalachari

The new Governor of the province, C. Rajagopalachari, paid him a respectful visit and congratulated him on the “miracle which he had wrought” (stemming rioting in Calcutta). But Gandhiji replied that he could not be satisfied until Hindus and Muslims felt safe in one another’s company and returned to their own homes to live as before. Without that change of heart, there was likelihood of future deterioration in spite of the present enthusiasm.

5. Talk with Communist Party members

At 2, there was an interview with some members of the Communist Party of India to whom Gandhiji said that political workers, whether Communist or Socialist, must forget today all differences and help to consolidate the freedom which had been attained. Should we allow it to break into pieces? The tragedy was that the strength with which the country had fought against the British was failing them when it came to the establishment of Hindu-Muslim unity.

With regard to the celebrations, Gandhiji said: I can’t afford to take part in this rejoicing, which is a sorry affair.

6. Talk to students

Gandhiji explained in detail why the fighting must stop now. We had two States now, each of which was to have both Hindu and Muslim citizens. If that were so, it meant an end of the two-nation theory. Students ought to think and think well. They should do no wrong. It was wrong to molest an Indian citizen merely because he professed a different religion. Students should do everything to build up a new State of India which would be everybody’s pride. With regard to the demonstration of fraternisation, he said: I am not lifted off my feet by these demonstrations of joy.

7. Speech at prayer meeting

Gandhiji congratulated Calcutta on Hindus and Muslims meeting together in perfect friendliness. Muslims shouted the same slogans of joy as the Hindus. They flew the tricolour without the slightest hesitation. What was more, the Hindus were admitted to mosques and Muslims were admitted to the Hindu mandirs. This news reminded him of the Khilafat days when Hindus and Muslims fraternised with one another. If this exhibition was from the heart and was not a momentary impulse, it was better than the Khilafat days. The simple reason was that they had both drunk the poison cup of disturbances. The nectar of friendliness should, therefore, taste sweeter than before. He was however sorry to hear that in a certain part the poor Muslims experienced molestation. He hoped that Calcutta including Howrah will be entirely free from the communal virus for ever. Then indeed they need have no fear about East Bengal and the rest of India. He was sorry, therefore, to hear that madness still reged in Lahore. He could hope and feel sure that the noble example of Calcutta, if it was sincere, would affect the Punjab and the other parts of India. He then referred to Chittagong. Rain was no respecter of persons. It engulfed both Muslims and Hindus. It was the duty of the whole of Bengal to feel one with the sufferers of Chittagong.

He then referred to the fact that the people realising that India was free, took possession of the Government House and in affection besieged their new Governor Rajaji. He would be glad if it meant only a token of the people’s power. But he would be sick and sorry if the people thought that they could do what they liked with the Government and other property. That would be criminal lawlessness. He hoped, therefore, that they had of their own accord vacated the Governor’s palace as readily as they had occupied it. He would warn the people that now that they were free, they would use the freedom with wise restraint. They should know that they were to treat the Europeans who stayed in India with the same regard as they would expect for themselves. They must know that they were masters of no one but of themselves. They must not compel anyone to do anything against his will.

From The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.