Piyoli Phukan, a landmark in Assamese movies, marks the coming of age of the Assamese film industry. It has left its 11 predecessors leagues behind – both in technique and in histrionics – and it can now be truly said that the Assamese movie has come past the adolescent stage and is, today, a full grown youth. Credit for the all round success of the film goes to director Phani Sarma who has also authored the story.

Following the success of Piyoli Phukan, a number of Assamese films made their mark at the national level, picking up recognitions at the National Film Awards: in 1957, Mak aru Maram (Mother’s love) directed by Nip Barua was awarded the Certificate of Merit; in 1958, the President’s Silver Medal was awarded, for the first time, to the film Ronga Police (Red Police) directed by Nip Barua; and the year 1959 saw the Assamese film Puberun (The Eastern Sun), directed by renowned Bengali film-maker Prabhat Mukherjee, declared the winner of the President’s Silver Medal. Puberun was also the first Assamese film to be selected for the International Film Festival held at Berlin. All the three films were related in the sense that they had social themes at their core. Nip Barua later established himself as a deft director of social dramas that appealed to a growing middle class audience. Gyanada Kakati, who made her debut in films through Parghat in 1949, starred in Ronga Police, and won critical acclaim for her role as the central character in Puberun.

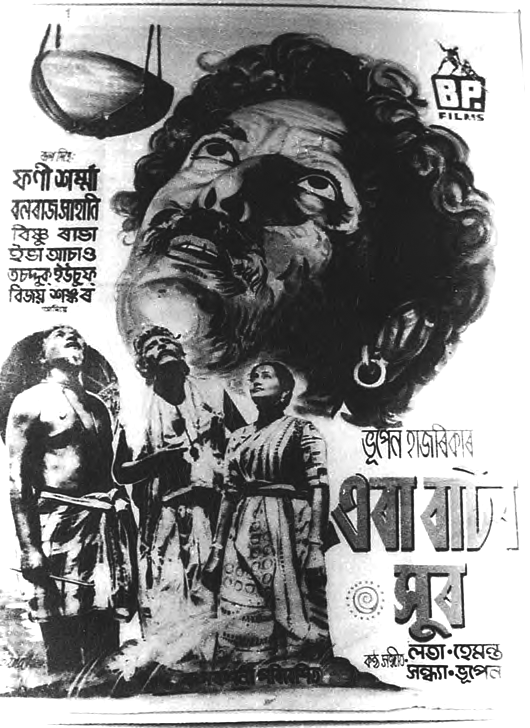

Paper advertisement of Era Bator Sur, first film of Bhupen Hazarika, 1956

Hazarika also made his debut as a director in the 1950s. He directed his first feature film Era Bator Sur (Tunes from the Deserted Path) in 1956. For the first time, an Assamese film had playback music rendered by famous singers from Bombay, and, most significantly, by the melody queen Lata Mangeshkar. It also had songs by Hemant Kumar, Sandhya Mukherjee, and Hazarika himself. The film also starred the famous Hindi film actor Balraj Sahni. Era Bator Sur was considered to be a commercially successful film and Hindustan Standard on 23 November 1956 reported, ‘The film introduces gifted new talent in the person of Dr. Bhupen Hazarika...The entire treatment is marked lyrical grace that one seldom comes across on the commercial screen. With this one picture, Dr. Bhupen Hazarika leaps into the film scene...Era Bator Sur undoubtedly opens a new vista of hope for Assamese films....’

Bhupen Hazarika directed seven Assamese feature films: Era Bator Sur (1956), Shakuntala (1961), Pratidhwani (Echo) (1965), Latighati (Turmoil) (1965), Chikmik Bijuli (Lightning Spark) (1969), Mon Projapaati (Renderings of the Heart) (1979), and Siraj (1988). Shakuntala and Latighati were awarded the President’s Silver Medal in 1961 and 1964, respectively. It is a matter of great regret that, except for Shakuntala, none of Bhupen Hazarika’s films are presently available. He was given the National Award for the Best Music Director for the film Chameli Memsaab directed by Abdul Muzid in the year 1975. He was also the recipient of the highest honour for cinema in India – the Dada Saheb Phalke award in 1992.

Socially relevant themes

The 1960s saw the production of 14 Assamese films. It was also around this time that the wonder of colour came to be experimented with for the first time in Assamese films, with Hazarika’s Shakuntala being partly made in colour. The 1960s saw four other Hazarika films which were replete with songs and dances, and playback singers from Bombay. Kishore Kumar, Mohammad Rafi, Manna Dey, Asha Bhosle, Talat Mahmood, Suman Kalyanpur, and Usha Mangeshkar lent their voices to Assamese songs in his films which became very popular among the audience. Even today, although the films are no longer available, people still remember and hum the songs of those films, and they are still played in radio stations frequently. Remixes have also been made of those songs. Special mention needs to be made of Hazarika’s Pratidhwani which was based on a Khasi story. At that time, the state of Meghalaya was yet to be born and Shillong served as the capital of Assam. Pratidhwani was a story that spoke about the relations between the hill people and the people from the plains. Overall, Hazarika’s films were socially relevant as well as enter- taining, with an eye on the box-office.

It may be observed that Assamese cinema till the 1960s was characterized by themes that were socially relevant. Film-making was not a purely commercial venture; it had a sense of social responsibility as well. Celebrating 30 years of Assamese cinema, Murali Choudhury in an article in the Filmfare writes,

Assamese producers can be proud of not having produced a single ‘unhealthy’ picture out of commercial considerations. Of the 35 films, 23 deal with social problems, three are biographical films, and the rest are musicals. Despite their limited resources, filmmakers are eager to depict life as they see it. Hollywood, with all its glamour, has not been able to humble Mexico, which has produced great films. Thanks to Rupkonwar J P (i.e., Jyotiprasad), Assam too has held its own as a worthwhile film production centre.

First crime thriller

Thus, an Assamese film which became a big box-office hit was Dr. Bezbarua, directed by Brojen Barua in the year 1969. It was the first Assamese crime thriller. It was also one of the earliest films to be shot in natural surroundings, rather than in studio sets. It was made with a budget of almost one lakh rupees. Dr. Bezbarua’s music was by Ramen Barua – the brother of Brojen Barua – and became very popular. The music rights were owned by HMV, and the songs were, till 2011, still available in audio tapes. The film was adjudged the Best Regional Film at the National Film Awards in 1969. In an interview with the author, actor Nipon Goswami, who played the young male lead in Dr. Bezbarua, reminisces, ‘Brojenda can be said to have established the growth of the Assamese technicians for he did not go to Kolkata to do the shooting, and he also started the system of shooting in real locations like actual houses instead of on sets.’ Brojen Barua also became the director with the Midas touch after he gave another hit with the film Mukuta in 1970. However, his untimely death brought an end to his blooming career.

The late 1950s and 1960s also witnessed the beginning of the establishment of the star system. Actor Bijoy Shankar, who made his debut with Hazarika’s Era Bator Sur in 1956, became a popular hero; and Eva Asao, who debuted in Sarma’s Piyoli Phukan in 1955, established herself as an accomplished actress. Bidya Rao, who peeped into the scene as a child artiste in Hazarika’s Shakuntala in 1961, became a full-fledged heroine in his Latighati in 1965, and went on to become one of the most sought after actresses of the time. Biju Phukan, who made his appearance in a dance sequence in Brojen Barua’s Dr. Bezbarua, went on to become one of the most popular heroes of his time. He is considered to be one of the most natural actors in Assam. His first release as a hero was Samarendra Narayan Dev’s Aranya in 1971, which was adjudged the Best Regional Film at the National Film Awards. Although Nipon Goswami, a Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) graduate, was the hero of the film Sangram (Struggle) in 1968, it was only with Dr. Bezbarua’s release that he tasted fame, and could establish himself as a hero. Both Goswami and Phukan shared the space as undisputed heroes in the 1970s and 1980s. They graduated to character roles in later years.

In sharp contrast to the 1960s, the 1970s saw the production of 58 films, and there was a gradual increase in the following decade as well – the 1980s saw the production of 63 films. This period can be termed as the golden age of Assamese cinema as films began to have mass appeal. Mainstream films like Brojen Barua’s Mukuta (1970), D’bon Barua’s Jog Biyog (Pluses and Minuses) (1971) and Toramai (1976), Nip Barua’s Sonma (1977), Bandhu’s Meghamukti (Freedom) (1979), Ajali Nabou (Naïve Sister-in-law) (1980), Nip Barua’s Koka Deuta Nati Aru Hati (Grand-dad, Grand-son, and an Elephant) (1983), Siva Prasad Thakur’s Bowari (Daughter-in-law) (1982), and Pulak Gogoi’s Sendur (Vermillion) (1984) succeeded in catching the imagination of the people and became runaway hits. Film enthusiasts still reminiscence about how people from villages would come in busloads to nearby towns to watch films like Toramai, Ajali Nabou, and Bowari. The 1970s also saw the production of the first coloured film Bhaity (Brother) by Kamal Narayan Choudhury in 1972.

Excerpted with permission of Oxford University Press, 'The Moving Image and Assamese Culture: Joymoti, Jyotiprasad Agarwala and Assamese Cinema' by Bobbeeta Sharma.