The name might not give it away, but Eddie Joseph, born Edwin Myers, was actually a Baghdadi Jew, a community with roots in Iraq that had a small but significant presence in India from the 18th century.

Myers's colourful life was among the several discoveries that Jael Silliman, an academic and activist, made while assemble an archive of Kolkata’s Jewish culture.

“It is like pieces of jigsaw puzzle coming together slowly,” said Silliman. “It may look simple, but I had to collect everything picture by picture, photo by photo.”

There were around 500 Jews in Kolkata in the 1970s, but today, after large-scale migration to Israel and other countries, there are only around 30. Two years ago, aware that many of the city’s remaining Baghdadi Jews were in their 80s and 90s, Silliman decided to set about recording their stories for posterity.

“Had I begun this 20 years ago, it would have been much richer,” she said. “On the other hand, people would not easily part with the originals of their photographs. Now, even if they cannot use the computers themselves, they can coax and cajole their children to email them to me. So the timing of this project is just perfect.”

From magicians to film stars, industrialists, politicians, filmmakers, doctors and musicians, the collection is an array of documents, photographs, letters and memoirs Silliman has collected over the past two years. A selection of these is already available online. From today, the Bethel Synagogue in Kolkata will install a permanent display of 30 posters crafted from Silliman’s material that will depict the evolution of Kolkata’s Jews.

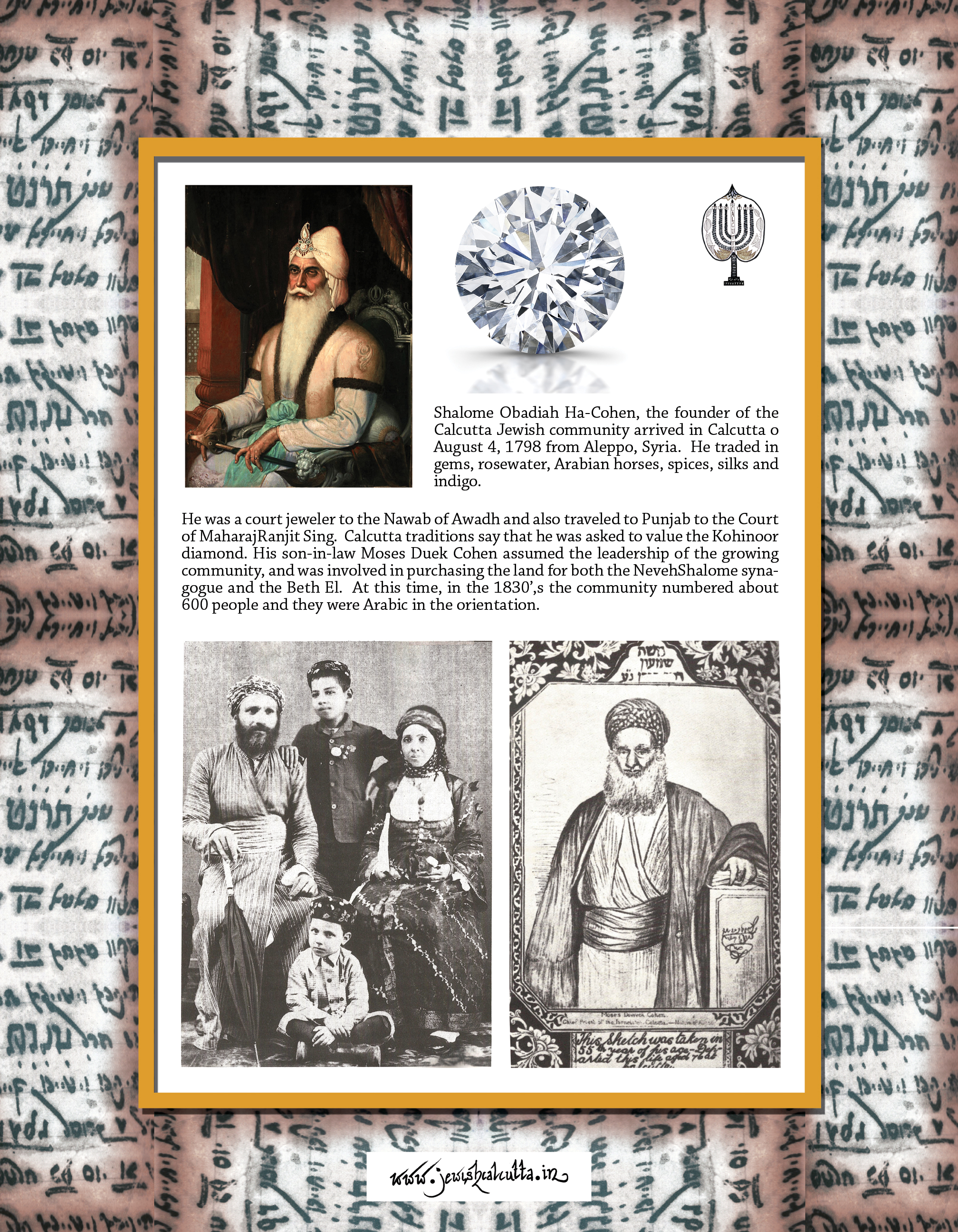

A poster from the exhibit.

The collection charts the last 200 years of the city’s Jewish history, during which the Iraqi refugees of the late 18th century began to adopt the dress code and habits of the British colonial rulers.

The community began to trickle into India because of persecution in their home lands. They came first as jewellers and took to Kolkata because the primary language of the city was then Persian. They spoke Arabic, even though they wrote it in the Hebrew script. (They also had a presence in Mumbai and Pune.)

But by the next generation, said Silliman, they had realised that to do well, they would have to learn the language of India’s rulers. Jewish children began going to British schools. Their first weddings followed Arabic traditions, but soon they began to adopt European customs.

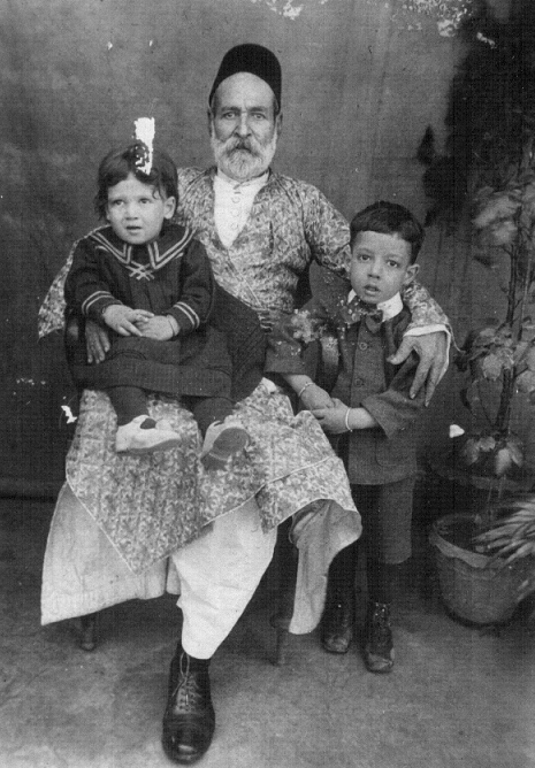

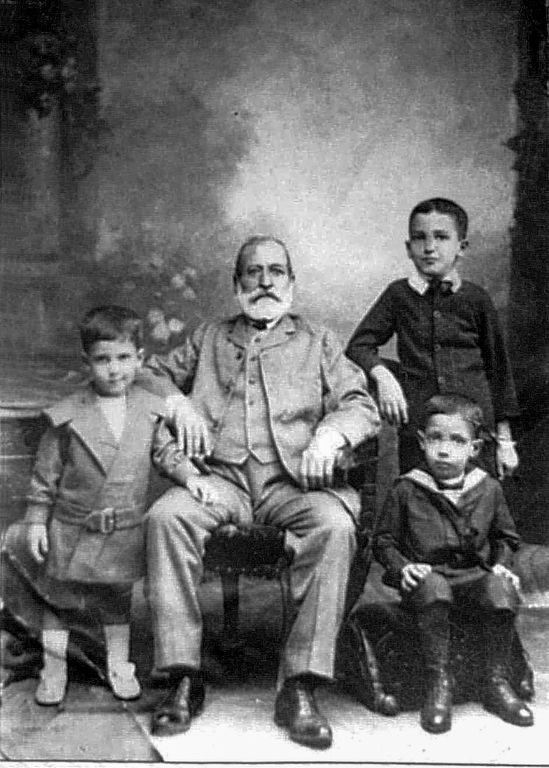

Some of these transitions were caught on camera. In one photo, Jonah Isaac wears Arabic robes with his grandchildren seated on his lap. A few years later, the same children have grown older and stand by their grandfather's side, along with a third child. All are now wearing Western clothes.

Jonah Isaac with Alec and Meyer, Recalling Jewish Calcutta.

Isaac Jonah with grandsons Sassoon, Alec (seated) and Meyer, Recalling Jewish Calcutta.

Silliman, a Nehru Fulbright scholar who lives in Kolkata and New York, is a scholar of women’s studies. A part of the collection is dedicated to Jewish women.

“Even I did not have a sense of how much Jewish women had done,” she said. “In a sense they were really trailblazers.”

Regina Guha, for instance, was the first woman to file a case to be appointed as a pleader in 1915. The Calcutta High Court denied her this opportunity. It would take another eight years before the government passed an act stating that women were qualified to be legal practitioners.

One of the first female dentists in India was also a Jew, Tabitha Solomon, who became one in 1928.

Silliman began with a scanty collection, but as the project went on, several members of the community approached her with their stories and photographs. Many of these photographs are from family albums that have never been published before.

“It is not comprehensive at all, but it gives a significant snapshot of the 3,000 Jews who made a significant impact on all walks of life,” she said. “Not all of them were rich industrialists. Many Jews were even quite poor.”

In addition to photographs of people, Silliman also collected images of artefacts and religious objects they had used over the years. There are also recipes for dishes like Calcutta Hamim and Fish Arook that are unique to the city, as its Baghdadi Jews adapted their food to local taste while still maintaining their dietary customs.

In addition to helping people from outside the community gain a richer understanding of Jewish culture, the archive is also a storehouse of memory for Jews who left the city years ago, but still remember it fondly.

Many were thrilled to see a video tour of the Magen David and Beth El synagogues with Arabic music playing in the background.

“To be able to sit and see the synagogue with the music in the background is very meaningful after all these years,” said Silliman. “This project has generated a lot of excitement with the older people. Some were reliving their memories. Others just wanted to share their rituals and stories.”

“This is the only country in the world where Jews were allowed to flourish – apart from a brief period of Portuguese persecution,” she added. “There is no field that was not open to them. That is pretty remarkable for a community here only 200 years."