We met with an interpreter at the Press Club of Mumbai. The meet was fun: we showed each other our cartoons and I remember the one he liked the most ‒ a cartoon about “marriage tourism” involving young brides from Hyderabad and older Arab men. He took it along with him, and it was eventually published in Charlie Hebdo.

Georges Wolinski, I realised later, was a big name in France. How big? When I was invited to an exchange programme in France and mentioned my purpose of visit ‒ a joint exhibition of cartoons with Wolinski ‒ the visa processing officer sounded a bit incredulous. “You have a photo with him?” he asked. “Can you show it?” He waived the processing charges. The typically grim customs officer, at 5 am at the Charles De Gaulle airport, when similarly told the purpose of my visit, said, “You know him?! He’s an icon here!” His face lit up, he smiled, waving me off without checking my bags.

French are different

Our exhibition of cartoons together in the city of La Rochelle had a unique concept: my cartoons of France drawn during my trip there juxtaposed with his cartoons and sketches on India. The opening was a grand affair, with the district’s mayor and the Indian ambassador attending it. I had asked about the dress code one may have to follow for the event and was refreshingly told by an organiser, “You are the artist of the show ‒ you can wear anything you want.”

The artist truly has a special place in France. Wolinski was awarded the Legion d’honneur by President Francois Mitterand. He later told me, a bit slyly, about the workings behind getting it, not unlike the process for our Padma awards. After the exhibition ceremony, the papers carried the news and photographs the next day. “Morparia, un frere,” said the headline, quoting Wolinski (“Morparia, a brother”). The next day we both took a train to Paris, and he was in another compartment (first class). At the station, in Paris, I could not find him. He had ostensibly left for home, without a decent goodbye. “Hmm,” I said to myself, “the French are different from us.”

It was after a few days that I got a phone call. “Hello, brother!” he exclaimed, perhaps aware of the ironical parting we had. And we soon fixed a meeting at his home. He lived in the toniest part of Paris, Boulevard Saint-Germain, in a splendid house. I was impressed enough to ask him if I could photograph it, a documentary proof of how well a cartoonist could do in life. Showing me a reclining figurine of a black woman, a fine specimen of African art, he said, “She is my wife.” He kissed it and added, “And I want to be buried with her.”

Courtesy: Clea Chakraverty

Freedom to offend

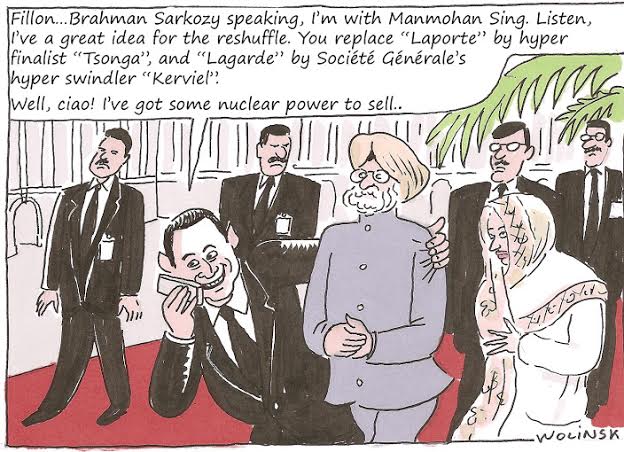

Charlie Hebdo is a provocative magazine. Everyone and everything is fair game. It is like the boy in class who enjoys pissing off every other boy, while revelling in the reactions that immediately follow ‒ of disgust, shock, anger and even threats. All this would only spur the magazine on. A mutual symbiotic relationship ‒ and a stable one, even. Till the eventual escalation. I used to argue with Wolinski about the purpose of being merely provocative. Wasn’t intention or substance also important? The constituency that the magazine addressed was already the converted (or un-converted). It was, well, preaching to the choir (see, one can’t get away from religion even if one tries).

The French take their freedoms seriously. “I’d rather die standing up than kneeling down,” said Stephane Charbonnier, the editor of Charlie Hebdo. They may have known of the danger, but death is a very high price to pay for the freedom to offend. French society today is in flux, as are other parts of Europe. The recent attack will help only further polarise views and erect barriers, between states, and also between minds.