Waves of immigration were altering parts of the nation. Rangoon, which once boasted an indigenous Burmese-speaking majority, including thousands of people from the Upper Irrawaddy Valley, transformed before the 20th century into a middling city for non-Burmese immigrants. The diverse origins of those pouring in produced a social milieu that was comparable to other British colonial port towns such as Singapore and Penang. In the newly defined, albeit poorly designed, cityscapes, a few immigrant communities were hard to miss.

Among them was the Hindustani.

An umbrella category used by the colonial authorities, the Hindustani referred to a group as varied as Bengalis, Ooriyas, Biharis, Tamils, Telugus, Punjabis, whether Hindu or Muslim. Their presence in colonial Rangoon was indelible. The Hindustanis dominated occupational niches, in the docks, railways, construction sites, factories and mills. Such was their prevalence that JS Furnivall, a colonial administrator observing Burma as a visitor in 1908, remarked: “…the Burman who would talk with the European in Rangoon streets must speak Hindustani”.

In this burgeoning immigrant demographic of Burmese Hindustanis, there was an intriguing figure who went by the name DA Ahuja. Little is known about this elusive man, save that by the first decade of the 20th century he was the owner of one of Rangoon’s popular photographic studios. In 1912, Ahuja became the proprietor of a British firm called Watts and Skeens, and soon thereafter he undertook the task of producing a hugely popular series of Burmese postcards. Ahuja’s total output of prints and postcards is estimated to be over 800.

The popularity of Ahuja’s postcards is truly amazing. His numerous images portraying a range of touristic Burmese scenes have a discounted listing on eBay (each for sale on average for under four pounds), an abiding presence on the internet, and even a Facebook page of their own. About 200 of the original postcards are lying in the Pitt Rivers Museum archive at the University of Oxford.

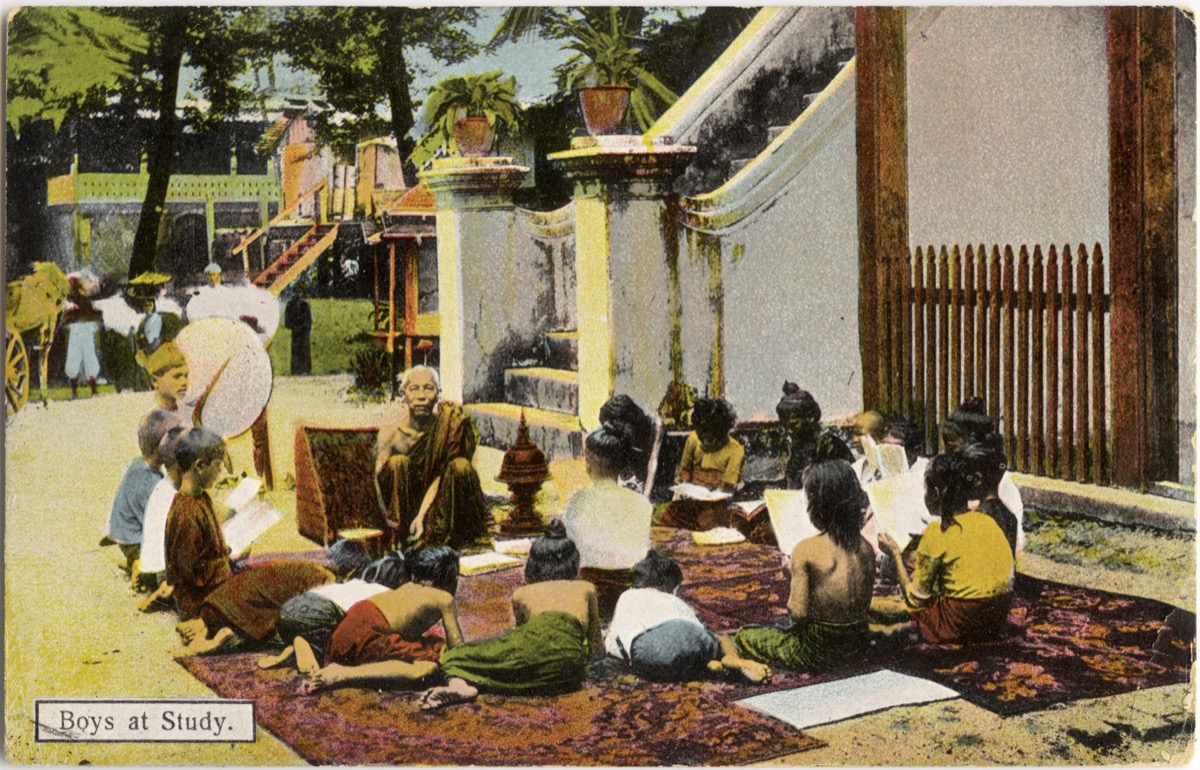

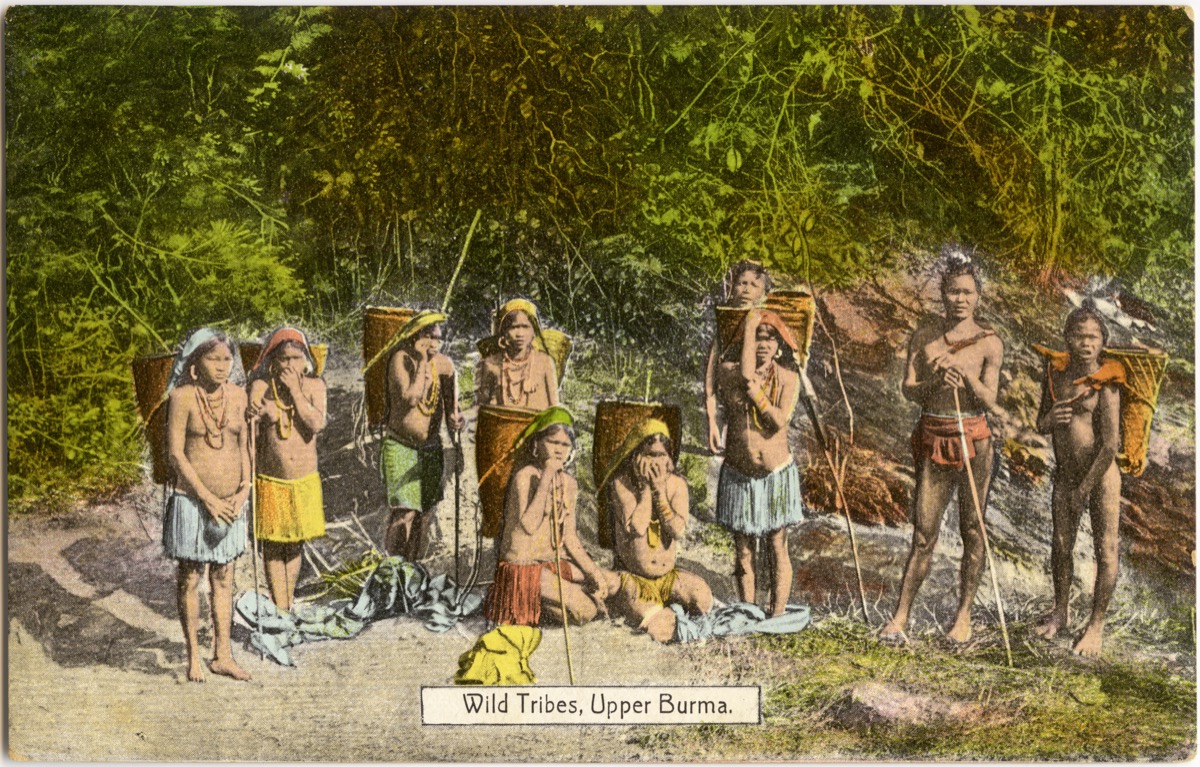

Arranged neatly in a green album, the postcards strike as conventional in content and parochial in their portrayal of the supposedly typical scenes of ethnic life – a muddle of village sites, cultural landscapes, and sacred shrines. The subtext of squalor is evident in a few of them, while in others this is touched up to create elegant multi-coloured locales, belles and Buddhists.

‘Boys at Study’

‘Wild Tribes, Upper Burma’

However, what needs to be highlighted most is the materiality of these prints. The postcards, carrying marks of their history, narrate tales that their online copies can’t. They bear testimony to the popularity of Burmese visuals, which were circulated around the world, as far as Italy, Lisbon, Cape Verde Islands, Paris and New York City. Some of the images I examined at Pitt Rivers Museum archive display signs of their handling – unfolded dog-ears and marginal discolouration, all of which only added to their authenticity. Above all, the postcards bear the exchanges between the senders and receivers.

‘A Shan Beauty’

See, for instance, this postcard sent to “Miss H.E. Fondran, 32 Whitehall Park, Hansen Lane, London” from Rangoon on May 11, 1907. The India Postage stamp valued at one anna is clearly visible on the bottom right corner. Below the obverse image of “A Shan Beauty” (referring to Burma’s north-eastern Shan Province) is the message: “Do you feel jealous, old girl? Tom.”

Unfortunately, due to lack of postal records for the album, one has to rely on creativity and imagination to wonder who is writing to whom, whether suitor to suitor, husband to wife, brother to sister, or perhaps son to mother?

‘Rangoon Jail- Prisoners carrying out their breakfast’

In another instance, a DA Ahuja postcard showing “Rangoon jail – prisoners carrying out their breakfast” carries a contrasting message overleaf: “Been away from the station and only returned last week. Very pleased to say we are having lovely weather at present. Also that I am enjoying the best of health and hope you the same. With best wishes, Yours sincerely, E Bracey.”

The incongruity of the image and the text couldn’t be sharper. The forlorn prisoners lined up with bowls for breakfast, some looking emptily towards the camera, seem a far cry from the salubrious conditions being described in the message. Since there’s no stamp and postmark, the postcard in all probability was exchanged personally or through a personal connection, or maybe, was never sent.

‘Mandalay, the Palace’

Behind the placid image of this Mandalay palace, from where the last King of Burma was ousted, is a fascinating exchange that was sent on May 6, 1911, by Maung Ba Haing (7, Pagoda Road, Rangoon, Burma) to Miss Dorothy Pinto (St Vincent, Cape Verde Islands).

It reads: “Dear Miss, Many thanks for your pretty card, received yesterday. This is a good view of the palace of the Burmese King at Mandalay. I hope you will like it. May I ask whether you would like to exchange photos with me? I should like to get your photo very much. Shall I send you my photo? Hoping you will reply soon. My best wishes for you. Yours sincerely, Maung Ba Phaing.”

One doesn’t know what transpired before or after this exchange. Who were Maung Ba and Miss Pinto, individually and to each other? What led Miss Pinto to share a “pretty card” with a man living miles away in Rangoon? And how will she respond to his request?

It is interesting to note that the same Maung Ba Phaing of 7 Pagoda Road sent a postcard of a “Burmese Festival Cart” to “Mr M J Andrade Mello, R Mousinho da Silveira 234, Porto, Portugal” on February 19, 1912. Unlike the postcard to Miss Pinto, this DA Ahuja print has no inscribed message. Could there possibly be any link between these messages sent by the same person within nine months of one another (though to two completely different locations)? Or a link between the individuals to whom these were sent?

‘Burmese Festival Cart’

The myriad representations of Burma, its peoples, landscapes and culture in the images need to be balanced against the textures of the postcard and their inked content. The presence of postmarks, dates, stamps and signatures, all make this archive immensely fascinating and incredibly entangled. Especially in a digital world, where representation is fast becoming akin to replication, it is significant to recognise particular histories of exchange.

Photographs, as Elizabeth Edwards remarked, are objects that exist in time and space and in social and cultural experiences. Therefore, the Shan Beauty, which HE Fondran received, is gestural and gesture itself. The image of Rangoon jail is incidental to the message of E Bracey, and at once reveals the dissonances of colonial order. And the postcard of Maung Ba Phaing to Miss Pinto is a gesture of gratitude (an image for an image) and an endearing excuse to communicate.

These myriad prints, which all found their way through DA Ahuja’s photographic studio are windows into a fascinating history of ideas, images, imperial dynamics and individual personalities. In themselves, each image is a corpus of subjectivities, and as a collection, they are multi-layered and multi-faceted. The connections with India, though indispensable, are only one thread in what is otherwise a prodigious movement of photographs, peoples, places, emotions over space and time.

The second part of this series can be read here.

All photographs courtesy Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

The writer wishes to thank Mr Philip Grover, Assistant Curator, Photograph and Manuscript Collections, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, for all his support and advice.