This is where my grandparents retired to from the Andaman Islands, bringing with them the most extraordinary memories, stories and all kinds of strange and exotic objects from their earlier lives. The estate and house once belonged to an Englishman named Crawford, whose spirit refused to return to its home across the seas, and lingered instead in this secluded house in southern India. There were antique flintlock guns and other curiosities that were mounted on the walls of an enclosed verandah that became a part of my grandparents’ new home, and his story often mingled with theirs.

All photos: Nithin Sagi

The house was already mellow when they acquired it, long and low, with a large tamarind tree in front, window boxes of geraniums and a tangle of garden; an old mango grove sprawled to one side. Later, fields of maize were planted in an empty patch, supplying us with fresh corn-on-the-cob with melted butter. A stony drive curved up to the porch, bringing occasional visitors, shaking the old house out of its routine, and then curved swiftly out in the opposite direction, taking them back to the wooden gate where a towering clump of bamboos whispered and rustled endlessly, leaving the house to settle back into its quiet ways.

If you walked around the back, past the cowsheds and chicken coops to one side, you could climb over a stile across a barbed wire fence into the filtered half-light that came down through the trees into the coffee estate. It was a strange underwater world of light and shade, and this is where grandfather was happiest.

Renaissance man

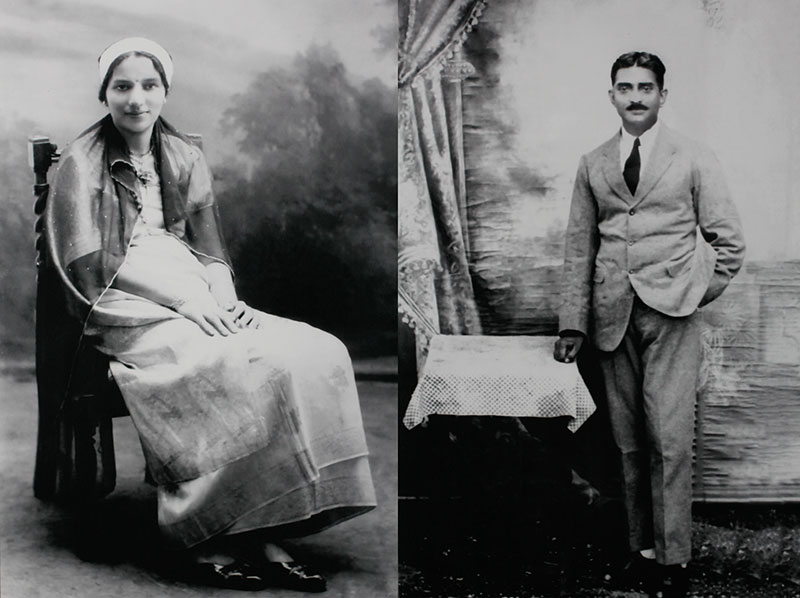

An austere, hardworking man, the forest was his world; his working plans for the Andaman forests made him a legend in his own time, but what I cherished, personally, was his article on the Shom Pen tribe, written after an official expedition to the Nicobar Islands that read like a classic, early anthropological report.

There was, however, another, very different world he had created and loved, a complete contrast to the wilderness he lived close to, most of his life. He had exquisite taste, and the house was studded with a lifetime’s collection of woodcarvings, chandeliers, elegant polished furniture, carved Chinese camphor chests, china, glass and scores of shells and corals, all glimpses of another, very different time.

A world within

The house was old, with creaky floorboards and dark panelling on the walls in places. It was a place of imagination, charm and haunting presences, the perfect backdrop for my grandparents’ unusual lives and the stories that seemed to follow them everywhere. Its spaces encouraged daydreams. The old house divided time within itself, taking on one character during the day and an entirely different one when night fell.

During the day, sunlight beamed in through skylights in the tiles, lighting up the beautiful, polished furniture, bookshelves and pictures, the cotton fabrics that dressed the beds and chairs and the pretty tea table decorated with flowers that was set out every afternoon.

At night, the whole world changed. For the first few years, there was no electricity, and every evening grandfather oversaw the small ceremony of trimming wicks and filling kerosene into brass lamps with glass chimneys.

The lamplight was low and warm. It glinted off beautiful old chandeliers, splintering into layers of colour. It threw deep shadows that wavered, advanced and withdrew. Sometimes it whispered stories. In the shadows, the Indonesian woodcarvings and fierce Yalis with protruding tongues and bulging eyes became more than artifacts: they became entire worlds, dark and strange, and made us think of lives lived on a cluster of islands covered in a dense tropical jungle in the Bay of Bengal.

Darkness lay thick around the house at night, and suddenly, the tales my grandmother told us were everywhere: they hid in crevices, and leapt out from deep, dark wooden wardrobes. Stories of hostile Jarawa tribesmen and friendly Great Andamanese; of fishing and swimming in the open seas, and hunting giant turtles in an outrigger with the chief of the Great Andamanese; of expeditions that grandfather went on to chart islands, and ghosts of Japanese soldiers, left behind on the islands after World War II. On grandfather’s desk was a paper-cutter made from a Jarawa arrowhead: it had been shot into one of their party while they were patrolling the jungles.

Epicure's table

We dined every day at a vast, dark, glowing table crafted from Andaman wood. Benjarong soup bowls in jewelled colours with matching lids lined a deep, recessed shelf, along with English china and coloured glasses. Ivy-patterned Noritake turned up on special occasions.

For grandmother, who married at 16, and left Coorg to live in the Andamans, every day was a celebration. She had the gift of turning ordinary occasions into an event. I never saw her cook, except for stirring an occasional pot, or hovering over a tray of coconut toffee, but she certainly knew how food was supposed to taste, and look, on the table.

She used the prettiest china and flatware as well-designed props on a stage set, so that every meal had the suggestion of extravagance and drama. The alcoholic, temperamental cook managed to turn out the most delicious meals under grandmother’s supervision. She loved lively company, was as loquacious as grandfather was silent. She also had a knack for managing people. Colourful characters, convicts from the infamous Cellular Jail at Port Blair staffed her entire household in the Andamans.

One of my favourite stories was of how she once had a Burmese cook who had previously been a river pirate on the Irrawaddy. His job was to carry the kerosene, douse a ship that had been attacked and looted, and set it ablaze. Grandmother certainly had a generous helping of the Coorg spirit and nerves of steel to help her along, and soon became one of the most sought after hostesses, known for her excellent table and lively parties.

Eclectic fare

At her estate home, her menus were eclectic, a mix of typical Coorg dishes – noolputtu and chicken curry, akki ottis and wild mushroom curry, as well as various other dishes she had learned to make during her life in the Andamans and Dehra Dun. There was a vivid tomato soup that I still dream of, with a slightly smoky sweetness, served up in bowls edged with a bright orange and yellow pattern that offset the contents. Her kitchen philosophy appeared to be ‘a little is plenty’.

I can’t imagine how else she could have kept her table so well supplied in such a remote location. Of course there were some advantages of being a long way from anywhere, such as the basket loads of wild mushrooms that came our way, along with wild game. Someone in the house would shoot every other day and more often than not, return with a brace of birds. One of the staff at the door, with an offering of game bunched in one hand was a familiar sight.

Of all the many feasts that I enjoyed over the holidays, I will always associate quail, partridge and green pigeon with that house. I loved the gamey taste of the birds, the flare of pepper and the familiar sourness of Coorg vinegar, kachampuli. Invariably, cutlery was abandoned, and fingers would pick the small, delicious birds clean.

Shadows in the dining room were always the deepest, the dark paneling soaking up all the trembling light from the lamps. There was something timeless about quail and partridge cooked with familiar spices eaten at a table crowded with three tiers of generations. Somehow, it connected us all with the small village in Coorg from which grandfather set out into the world to make his life, and carried us in a wide arc to those faraway islands, enmeshed us in a series of extraordinary lives, and brought us right back to where we were, hoping, one day, for stories of our own.

My grandparents managed to carry their limitless inspiration, creativity, energy and a particular sense of mystery everywhere they went – even deep into retirement.

Coorg style quail

I loved the taste of the game birds I ate as a child at my grandparents’ home. After many experiments, here is my recipe that comes closest to the flavours that I remember. It is served here with stir-fried mushrooms the way we cook them in Coorg.

Ingredients

* 1kg dressed quail (approximately 9 birds)

* 250 g shallots, peeled

* 1 ½ tbsp freshly ground pepper

* salt to taste

* 4 green chillies, minced, or 7 to 9 Coorg birds' eye chillies, left whole

* 100 ml oil for frying

* 1 ½ level tsp cumin, dry roasted and powdered

* 2 tsp peppercorns, dry roasted and powdered

* 1 ½ to 2 level tbsp kachampuli, or juice of 2 limes

Method

* Wash and pat dry the quail. Mix in the green chillies, salt and pepper, rubbing into the cavity and under the wings.

* Cover and leave to marinade to absorb the flavours in the fridge for 1 ½ -2 hours.

* Remove birds from fridge and bring to room temperature for about 30 minutes.

* Truss the quail with butcher’s twine, trying around the centre, turning the bird over, tying again, and then tying the feet together.

* Heat the oil in a pan wide enough to hold all the birds at one time if possible. Or else, fry them in batches of 4, taking care that they do not stick to the bottom of the pan, or burn.

* Add the shallots, and fry gently until softened, then remove from the oil and set aside. Add quail and fry on low-medium heat until browned on both sides.

* Remove the quail when done, approximately 15 to 20 minutes. Set aside and fry the remaining birds in the same way. Add a little more oil if necessary.

* Return the quail and the reserved shallots to the pan in batches, and using your fingers, take pinches of the dry roasted cumin and pepper, and sprinkle onto the quail, stirring to blend and cook for a few minutes.

* Taste for spice levels, and add more roasted ground pepper if you wish.

* Add 1 ½ tbsp kachampuli, and stir a few times over low heat until well mixed. Test for sourness, and if you would like some more, add another spoonful of kachampuli. Serve hot.

Cook's Note : The pepper powder smeared onto the quail in step 1 is not roasted. You can increase or decrease the spice levels according to taste, but the dominant note should come from pepper. Quail is a delicious bird that takes well to these spices. Farmed Quail is available from suppliers in Bangalore.

This article originally appeared on the writer's blog, kaveriponnapa.com.