Long, long ago there was a group of people who were not aware that they were human. They lived like animals in jungles, in caves, in hills and on mountains. They may be there even now. They were known as the Halakki tribe. They cooed and twittered to one another, like birds, and wandered about eating whatever they could find. They were meat-eaters, cannibals. They would lie in wait and pounce on anyone who came their way and kill them to eat them raw. They did not even know the difference between humans and animals. There was no room for any awareness of pain or loss. They would also venture towards the edge of the forests sometimes. But they did not stay longer than a day or two anywhere.

Subba was their leader. Everyone had to listen to him. Once, they were near a small village. Each man walked down a different pathway shouting, “Halak … Halak”. One of the paths led right to the edge of a village. The man walked about and found himself amid a row of huts. In one of them, he saw a young girl with a baby at her breast. The baby was sleeping. Soon, the girl laid her baby in a cloth-swing-like cradle and went inside. The Halak who had been watching her stealthily, came forward and walked away with the baby, still asleep in its wrap. The mother came outside, saw the cradle swaying a little and went inside, presuming her baby was still in it.

In the jungle outside the village, the leader of the tribe awaited his men. Most of them returned empty-handed. Only one of them offered him a bundle. When the leader opened it, he was in for a delicious surprise. Inside the wrap was a tender baby. Their joy knew no bounds. Here was a celebratory meal.

“What a festive meal!” they said, thumping the man on the back. The leader had to take the first bite, of course, be it the ear or nose or palm of a hand. The rest could take their turn only after him. And so, he took the little bundle of a baby and stared at it. The baby was cute. It was slowly waking to his touch. It opened its eyes. They were wide, blue-black and sparkling. He was fascinated; he kept staring at the chubby face. The baby too stared at his, all painted and scary. And the baby gurgled, instead of screaming in fright. The old man was astonished; this was so very different from the responses of his previous prey.

“Hey! What is this?” he murmured as he felt an unusual attraction.

The baby kept staring at him and laughed again, loudly this time. The man felt a strange kind of pain, a concern for another he had never ever felt before. He wanted to keep staring at the creature in his hands. He could not get enough of those clear, dazzling eyes, that bud of a nose and the laughing mouth. He had not only forgotten what he was supposed to be doing; he had even forgotten himself. Hardly aware of what he was doing, the man touched the baby’s chin, slowly, gingerly. He felt a strange delight, a thrill coursing through his veins. The baby felt tickled; it laughed louder. That laughter seemed to be telling him something.

“What’s this?” said Subba, unable to understand; unable to control a grief welling up. “I’m feeling strange. Abah! What an infant! It’s sharing so many mysteries through its laughter. Abbabbah! I can’t! I’ll be ruined if I eat it.” And turning towards the man who had brought the baby, he asked, “Le, from where did you bring this?”

“From one of those huts,” he responded.

“Was the baby alone?”

“No, the mother had just fed the baby. When she laid it in the cradle and went inside, I carried it away.”

The leader began to weep. “The mother must be weeping for her baby. No wonder, I’m crying too. Ayya, go and put the baby right back where it was lying,” he said. And he touched the baby’s chin with trembling fingers, saying, “Go … go back to your mother.” Wrapping the baby in its swaddling cloth, he handed it over.

As the man neared the house with the bundle, he saw quite a crowd milling around. Creeping stealthily, he laid it carefully on a ledge and disappeared. The baby, who had been laughing all that while, began to bawl now. Everyone rushed towards the sound and they were surprised to see it. The mother hugged her baby and wept tears of joy.

After watching the scene stealthily, the man returned to his people and told them what he had seen. Subba, their leader, was trembling. So was his voice. He got his people to sit before him and he began to speak. His face had an unusual glow and also an indescribable pain as if some kind of fear had gripped him. The others wondered while listening to him: Why was their leader trembling? What could have happened to him?

“Have we ever trembled? Have we ever known water to flow unbidden from our eyes?” Subba asked them.

“Never! Never!”

“Look, there was a time when you brought an old man. You haven’t forgotten him, have you?”

“We remember! He had a string hanging from a shoulder.”

“Ayyo! Whatever he told us that day has come true. ‘Can you do this? Being human?’ he had said. And then he had moaned, ‘Oh God! Where’s your compassion?’ How I wish our hands had become limp that day! That our eyes had dimmed! But see what we’ve been doing … all that we shouldn’t be doing! I could hear every word he said in the laughter of that child. As if the child was amused, as if it had whispered, ‘Le, you’re human, are you?’”

“Yes, my people, we’ve done wrong; a great wrong. That day, when that old man called out to Him, God didn’t come. But today, He came to us in the form of this baby. Now we know that we must have fear. And also, fellow feeling. We too are human. Can we eat our own kind? No, not anymore. Enough of this way of life! From now on, let’s not take another life. Let’s eat what we can get; let’s starve when we don’t. Only, let’s not kill anyone for food any more. You can go anywhere you please. If you want to be with me, you’ll have to be like me.” And the leader walked away.

Everyone walked behind him, in silence.

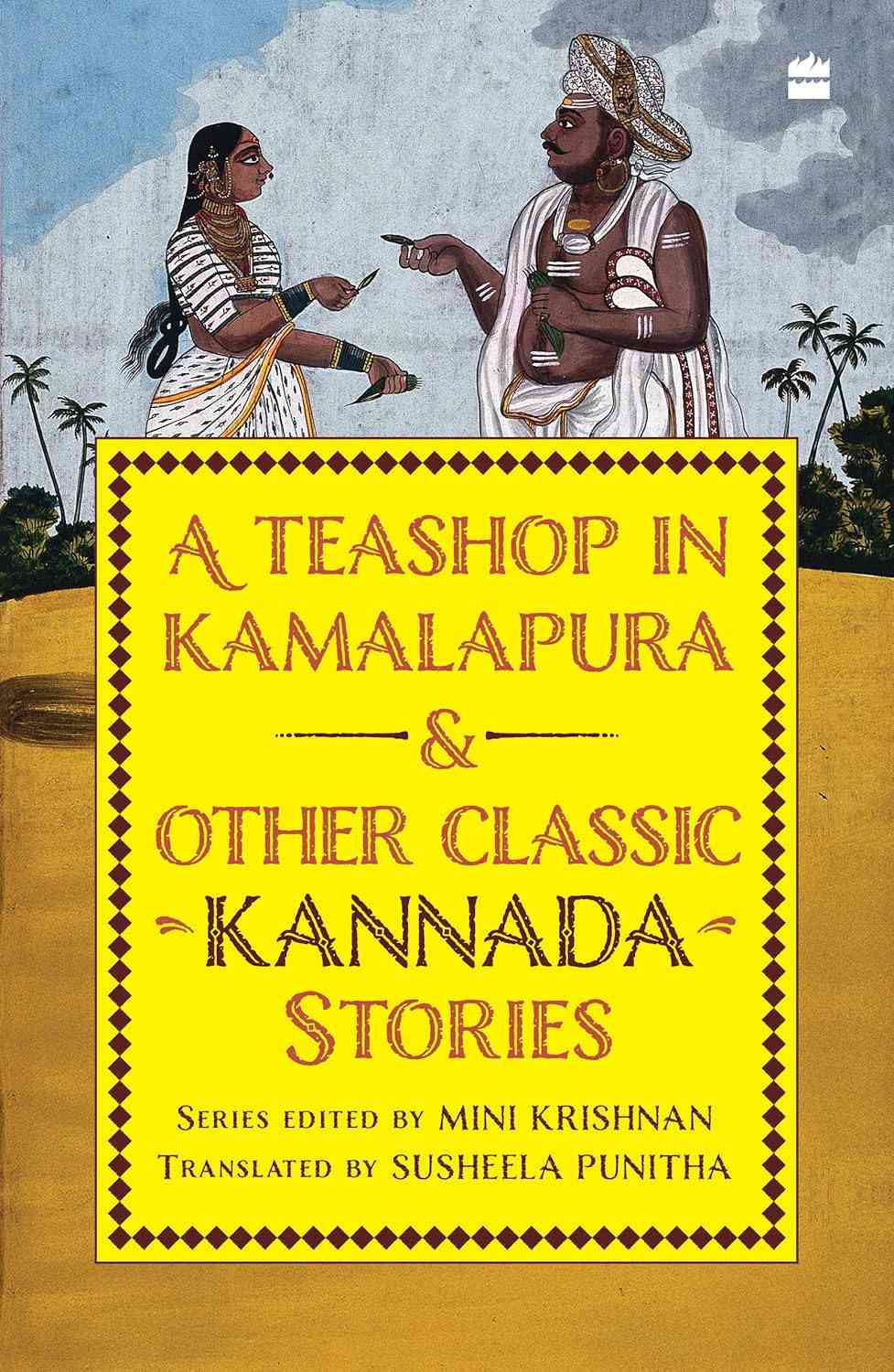

Excerpted with permission from ‘The Child, A Teacher,’ by Nanajangudu Thirumalamba in A Teashop In Kamalapura And Other Classic Kannada Stories, translated by Susheela Punitha, series edited by Mini Krishnan, HarperCollins India.