Devangana Dash is a book designer, art director and educator, and the most recent winner of the Oxford Bookstore Book Cover Prize. She won the prize for designing Conversations with Aurangzeb, written by Charu Nivedita and translated from the Tamil by Nandini Krishnan.

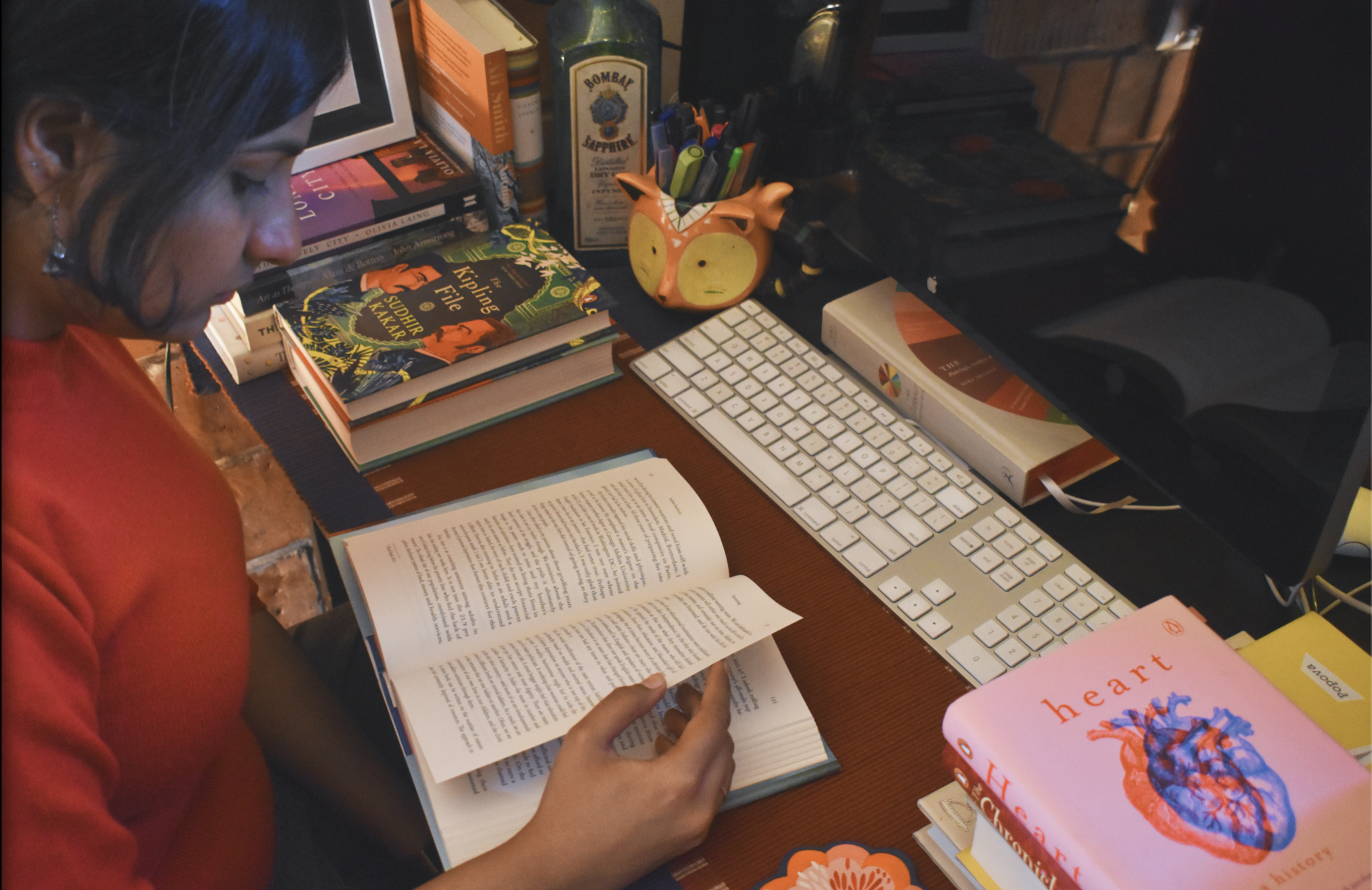

In addition to designing books, she is also an illustrator and author of a children’s picture book called The Jungle Radio: Birdsongs of India. Her art and stories mostly use visual autoethnography, and find roots in community, conservation, education, childhood and mental health. For inspiration, she relies on children’s picture books, folk art, Urdu poetry, synchronicity of life events, art therapy, the ocean, and her two cats. She spoke to Scroll about her long years of designing and her aesthetics.

In a conversation with Scroll, Dash talked about her book-designing philosophy, the design sins she’ll never commit, creating covers for perennially bestselling authors like George Orwell and Kahlil Gibran, and how artificial intelligence can enrich a designer’s work with “intention and care”. Excerprs from the conversation:

How did you start designing book covers? Do you remember the first time you thought that you could live happily doing this? Is there a cover you are especially proud of?

My journey into book design began at home, where I first developed an appreciation for books and visual aesthetics through my father’s collection of interior design magazines. I always drew as a child, and eventually I learnt some software on my own and experimented with digital collages and image editing and designed posters for events. During my time studying visual communication design in art school, I began to see books through a more nuanced lens – considering illustration, layout, production, packaging and the tactile experience of reading. I started making illustrated books, wrote stories and discovered a strong pull toward visual storytelling, which led me to consider applying to a publishing house.

A full-time role at Penguin Random House soon followed, where I truly began designing book covers and gained invaluable hands-on experience. I haven’t stopped designing covers and now design for publishing houses globally. Over the last ten years, I’ve had the privilege of shaping the visual identity of many stories that matter, collaborating with authors, editors, illustrators to bring narratives to life. The joy of this work lies in its collaborative nature – each cover is a conversation between story and reader, and between text and image. There’s nothing quite like holding a printed copy of your design fresh off the press; it’s a moment that continues to reaffirm my love for this craft.

It’s hard to pick a single favourite – each cover carries its own memories and creative risks. But I’m particularly proud of the bold visual choices made for Goodbye Freddie Mercury, Nadia Akbar’s debut. Conversations with Aurangzeb by Charu Nivedita, Nandini Krishnan won me the best cover design award after a decade of making book covers, so that will remain special.

Reimagining Maximum City by Suketu Mehta and The Music Room by Namita Devidayal were also a full-circle moment for me – I had read both books as a student, never imagining I’d design their re-jacket editions years later. Other projects close to my heart include the HarperCollins India Classics series, Orienting: An Indian in Japan by Pallavi Aiyer, The Essential Manto-Chughtai for Penguin Classics, and the series design for The Partition Trilogy by Manreet Sodhi Someshwar. There are many more that will come to me the minute I stop answering this question.

How do you turn a book into a piece of art? What is your design philosophy?

Turning a book into a piece of art begins with a design thinking process. It is the intent to create something that is visually striking, contextually appropriate, and intellectually engaging. A good cover balances form and function – it sparks curiosity without giving everything away. Designing a cover involves an intentional but also intuitive sense of proportion: how much do you want to reveal, how much should you hold back? How far can you push a visual idea, and when is it wiser to play it safe? There’s a quiet tension in that decision-making. You’re communicating through suggestion rather than declaration – creating intrigue, not spelling out the entire narrative.

My design philosophy is very simple and rooted in restraint, clarity, and respect for the story. A book cover isn’t a billboard – it’s a visual entry point. It works alongside the author’s voice, the publisher’s identity, the cultural moment, and the reader’s imagination. It’s one piece of a much larger conversation, and often, the smartest thing a cover can do is not try to say too much. There’s also an element of surrender in the process. As designers, we contribute to a collaborative ecosystem that includes the weight of the author’s name, the allure of the title, the publisher’s legacy, and the reader’s expectations. We must trust that these elements are already doing some of the heavy lifting. At the same time, the cover must live in dialogue with the present – it needs to feel relevant and honest. In the pursuit of cleverness or trend-driven design, it’s easy to mislead or over-promise. But design, like storytelling, is a learning process. When something doesn’t land, you listen, reflect, and evolve.

How do you visualise your cover? Do you read the text or is an editor’s brief more helpful?

It almost always begins with the brief sent from the publisher, with specifications on format, genre, as well as visual suggestions or comparative books. A well-articulated brief can be a designer’s best ally – it sets the foundation for a fluid and collaborative relationship between editor, author, and designer. When done thoughtfully, it offers just the right amount of context, tone, and direction to begin visualising the book.

For fiction, I often read a few chapters to immerse myself in the story and pick up on recurring or significant motifs – objects, settings, character traits – that can be translated visually. If the manuscript is compelling, I’ll read it in full. At times, just reading the introduction, foreword and some select chapters is enough to grasp the tone, subtext, or philosophical undercurrent of the book.

My visualisation process varies with each project, but it typically begins with idea-mapping – sketching thought webs, themes, collecting references, and identifying symbols and metaphors. I look for visual anchors: the emotional undercurrents, the spatial cues, the subtleties in character. This stage is less about execution and more about discovery – finding the visual vocabulary that will eventually shape the cover. It’s about gathering the right visual companions that will stay with me through the process. This is the more exciting but frustrating stage, you are hunting and you are very, very hungry.

How do you go about designing a book cover? Is it all digital or are your first sketches made by hand? And how long does it usually take?

For me, idea generation, planning and execution often happen simultaneously. I think with the medium. If I’m working with photography, I start visualising the image in my mind and begin the research. For archival material, I think of ways to use the image in contemporary ways. If it’s an illustration-led cover, I need to sketch – either on paper or digitally. My first response is usually handwritten: I jot down keywords, visual cues, and even start thinking in colours. These notes become the scaffolding of the concept. Sometimes, I sketch quick thumbnails on my iPad – tiny explorations of composition and layout. I block out spaces for the title, author’s name, subtitle if needed, and begin to test visual rhythms. These early drawings are not about perfection; they’re about finding the right visual entry point.

There’s no fixed formula or timeline – it really depends on the book, the brief, and how easily the concept resolves, and who your client is. I’ve designed a final cover spread in three hours, and I’ve also spent three months wrestling with one that just wouldn’t fall into place. On average, the process from concept to final approval takes anywhere between three to five weeks, especially when multiple stakeholders are involved. Once the front cover is locked in, the rest – spine, back cover, flaps – usually come together much faster.

For someone who has designed both classic and contemporary books, how different is it designing a cover for a classic? What are some things that you are especially attentive to?

A good design is so much about reinvention. A classic carries the weight of history, cultural relevance, and reader nostalgia. A classic already has a loyal readership, and the cover becomes less about introducing the story and more about celebrating it. It needs to feel timeless, just like the text itself. That said, I don’t see classic and contemporary titles as entirely separate genres. (Controversial opinion!) The fact that a classic still has readership today is a testament to its lasting relevance. So, as a designer, my role is to ensure the cover speaks to a new generation of readers without alienating long-time admirers – a delicate balancing act. There’s often a misconception that classic covers must look vintage or traditional. I actively try to challenge that. A reimagined classic doesn’t have to rely on visual clichés. In fact, it’s an opportunity to bring a fresh lens to a story that has stood the test of time.

When publishers commission new editions of classic texts, I see it as both a strategic and creative opportunity. Yes, it’s about delighting existing readers, but more importantly, it’s about making the book accessible and inviting for younger or first-time readers. My job is to design a bridge between the past and the present – so the book feels relevant, desirable, and emotionally resonant all over again.

Your fiction covers are more colourful and have a collage-like style, while your nonfiction covers are subdued and spare in details. Tell us about these choices.

Design is decision-making at its core. Colour, for me, is not just about brightness or visual appeal – it’s a voice, a mood-setter, a critical element that shapes the reader’s first impression. Fiction often gives you the freedom to imagine and construct a world that the reader has yet to step into. The pace of fiction is usually more dynamic, and the writing more experimental, abstract – so collage-like treatments, rich colours, layered imagery, and expressive typography often become natural choices. These elements help evoke the emotional tempo and narrative texture of the book.

Non-fiction, on the other hand, often calls for restraint. It demands clarity, a different kind of credibility. But even here, colour and composition play an essential role – they just operate more subtly. I’ve designed serious non-fiction in soft, powder pink with classic typography, and used collage techniques on business or memoir titles. So I don’t follow fixed rules – rather, I respond to the tone, context, and intention of each book.

Any designer with experience in this industry develops a keen understanding of the market – what shares shelf space at a bookstore, what stands out at an airport kiosk, what draws attention online. Those cues are crucial, but so are the genre, the audience, and the voice of the book. Ultimately, it’s about balance. My process is intuitive but informed – I assemble visual elements that respond to the content, resonate with the intended reader, reflect my own visual sensibility, and still feel fresh within the market landscape. This instinct is something that sharpens with experience.

Tell us a little bit about designing the Harper Classic series – the bold colours, minimalist designs, the sharp geometric shapes. What did you have in mind?

With classics, half the job is already done – the books have a dedicated readership. Your task is to design in a way that honours their legacy while also bringing something fresh. The challenge is

to avoid alienating loyal fans, but as with any creative work, there’s always room for critique and differing opinions.

Designing the Harper Classics series was an exciting opportunity. I worked on 11 titles, though only six of my designs were eventually published. Since the publisher was launching a new classics imprint, I initially focused on using the brand’s core colours. As I’ve mentioned earlier, classics must speak to contemporary audiences as well. The packaging needs to resonate with what will sell in today’s market. So, taking a spin on the classics, we took a modernist approach inspired by Bauhaus design. Colour becomes a primary design element in this series design strategy, initially envisioned with three primary colours, with a lovely edition of a fourth colour for the fiction titles.

To make the covers playful and intuitive, and accessible to readers of all ages, I created a minimalist yet vibrant design system. Abstract, geometric and minimalist illustrated motifs were conceptualised for these powerful, timeless stories, gently inviting the narrative interpretation of these texts. For example, the blue and yellow circles on The Communist Manifesto symbolised class conflict and coexistence. The artwork on Orwell’s 1984 conveyed the theme of surveillance, the mysticism in The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran inspired a kaleidoscopic motif. The bold, solid shapes and colours are further complemented with clean, sans-serif typography in black and white. The result was a series design that was simple, intriguing, produced with a premium matte finish and was very well received.

According to you, what are some of the cardinal sins of book cover designing?

I’m unsure about cardinal sins, but there are common errors designers can make and I’d note a few points here, learnt from my experience:

Misleading your audience: If your design strays too far from the genre or the story, it can mislead or confuse your intended readers. Each genre has its own visual language. For instance, a romance novel cover will differ from a sci-fi thriller, and the design should reflect that genre’s mood.

Using too many fonts, difficult-to-read styles, or chaotic arrangements can make the cover look cluttered and confused.

Too overwhelming or overcomplicated design: Not every element on the cover can carry the same weight. Choose what needs to be emphasised. Overloading the cover with too many ideas or too much visual noise can dilute the message. Keep it simple.

The cover is not a summary of the book; it is an invitation.

Blindly following trends and overdoing it: As a designer, it can be tempting to indulge in trends, but it’s important to evaluate whether that trend actually serves the book or its audience. Sometimes, a trend might be visually appealing, but contextually irrelevant to the story.

Not designing for different formats: A cover that looks stunning in print may not necessarily translate well to digital platforms. It’s important to consider how your design will adapt to various formats – e-readers, thumbnails, or large-scale posters, merchandise – and ensure it remains effective in each context.

When you go to a bookshop, what are the kind of covers that immediately draw your attention?

I’d say my choices are closely tied to my reading habits. While my own book covers – especially for fiction – might appear colourful and bold, as a reader, I often gravitate toward nonfiction, research-driven works, and commentaries on our current times. Books, creative practice, pedagogy, and conversations around culture and design really draw me in. So, I naturally tend to notice covers that feel quiet but confident – those that don’t shout for attention, but hold it once you look closer.

I deeply admire thoughtful production design – when a book cover is not only visually compelling but also beautifully crafted in its materiality. I also find myself picking up books designed by my contemporaries or author-friends – people doing meaningful, thoughtful work in the community. Sometimes the cover draws me in first; other times, it’s the familiarity with the designer’s voice or the subject matter that pulls me closer. I think I look for design that feels intentional, where the choices are not just aesthetic, but rooted in the content and tone of the book.

There are some publishers who are using AI to design book covers. They are not beautiful but they are quick and cheap. Do you consider AI a competition?

Books will, hopefully, always retain the human touch. We can’t fully eliminate the soul of books by surrendering to AI. It may flatten the emotional complexities that are involved in the creative and literary processes. While AI can certainly support us and enhance efficiency – and I do hope publishers are using it thoughtfully and sustainably – it should never be used in ways that dilute the craft of book design but instead can be used to streamline publishing processes. It is not a direct competition, it may enhance human voice but not replace it.

With great power comes great responsibility, and I’m hopeful that, sooner or later, the creative industry will embrace this mantra too, and use AI not as a shortcut, but as a tool to enrich our work with intention and care. The final choices of the messaging on the cover should hopefully remain in human hands for a while. It is our responsibility to keep these discussions alive and explore possibilities, but it is also essential to bring the human back into this work.