Kato shot the flat pebble over the small lake’s placid surface, causing a ripple to streak across it like the Thalaxu’s web. Lakhi, kini, kuthu, bidi, pungu, tsugho… he counted to six before the stone finally disappeared into the water with a satisfying plop! Chuckling to himself, he bent to retrieve another missile from the teetering heap at his feet.

“Oizao! Dear mother! What are you still doing here, you rascal!” A very annoyed voice thundered into his solitude.

He picked up his satchel and watched his mother storm towards him, cane basket swinging from her back. “Get going this instant or I shall whip the skin off your buttocks!”

Stooping, he picked up one last stone, this one as black as his mother’s hearth, and whiffed it onto the water before running away, shooting a defiant look at his tormentor.

If he’d stayed to count, he’d have noticed that the stone skipped over the water thrice before it vanished above the lake. The spot where it disappeared mid-air shifted like the air sometimes does on a really, really hot day – one moment it was there and the next, it simply winked out of sight. But Kato was already racing up the slope, and whatever game was afoot hung in his absence like an unfinished poem. Maybe this game would have an ending, maybe it was never meant to be. For now all Kato cared about was getting as far away from his irate mother as possible.

The mountainside was awash with a fiery blush. In the span of a few hundred steps the concentrated redness quickly dissipated into the gradients of the spectrum until it settled on light orange. In this moment, the village looked like a place halfway between dreams and the waking world. Kato climbed a small boulder for a better view. He closed his eyes, inhaled the sharpness of the cold mountain air, and hopped off with a satisfied smile.

Baring his canines like a fox in hot pursuit, he raced up the steep incline effortlessly, carried on by his windswept feet. Kato sometimes thought that his mother had snatched him from the air, as he, a wind spirit, blew over her garden. He’d always been fast. So very fast! He continued to role-play the fantasy of a snatched wind spirit until his eyes glanced down at his old half-pant fluttering around his thighs like a harassed flag. He laughed aloud and slowed his pace into an easy walk.

Somehow, he doubted that a Sumi wind spirit would ever consent to wear a half-pant, no matter how reduced its station was. He knew that his father had worn nothing but a woven kilt when he was a boy his age, but then the white man had come and told them that they were indecent and needed covering. Now, only old Futhena – the harrier of children, enemy of all that is joyful – still stubbornly wore the kilt in the whole village.

The white men mostly left them alone but even Kato could sense that with their arrival the mountains had taken note and turned sideways like someone trapped in an uneasy dream. These people had brought more than half-pants and funny-looking hats to his mountains. The first time he’d seen one of the English guns at work he’d been both fascinated and terrified in equal measures. There had been a deafening roar and the great melon perched on a rock had been blown into smithereens within a blink. The memory still filled him with a prickly feeling.

He slowed down his steps to a dragging gait when he saw the empty ground in front of the schoolhouse. He was late and classes had already begun. He fought the urge to turn back the way he’d come.

The school, a single-thatch house with one big room, stood like a jovial, portly old man in the northern end of the village. Just above and behind it stood the grand council hall where all important matters were discussed. The village – Ayito-phu – was located on the top western flanks of a mountain, a strategic choice that had made it virtually unassailable during the old days of headhunting. If one were to be completely factual, the days of headhunting were neither old nor gone, for in the areas that bordered Burma there were still tribes who took great delight in lopping off heads and stacking skulls like the macabre hoard of some unknown devil.

From a distance he could already hear the children roaring raucously as the teacher tried in vain to quiet them down. Children who had previously accompanied their parents to the jhum fields or made mischief all over the village now had to discipline themselves into sitting in the same place for hours – a thing the students hadn’t quite learned to tackle. After all, the school was hardly more than a year old.

Just outside the doorway he paused for a moment and regarded the hornet’s nest inside. He felt his strength waver. The thought of all the eyes inside, the minds he couldn’t read, the faces that could be hiding disgust or worse yet, pity… He drew in a shaky breath and cursed himself for being late. Exhaling slowly he pushed a foot into the dimness of the classroom.

Like a waning storm the uproar settled into a murmur. Aghoto, the only teacher in the school, motioned him inside. Catching sight of his friend Apu, he quickly walked over to him, the back of his neck burning from the eyes boring into him. The scrawny boy pulled him down onto the bamboo bench hard.

“Kato, you are late,” the teacher stated flatly, almost as if he was making an observation about the weather. Kato in turn nodded and looked down at his dusty bare feet. The teacher sighed in resignation before turning his attention back to the class.

The class let out a collective sigh of relief. Kato was a mute, so it wasn’t the silence itself that unnerved the children; they’d never heard him make a sound, except for the odd huh, or mmmh. He’d never made a scene but even the very minuscule possibility of some unexpected reaction, the most unlikely chance that he might respond somehow, built itself into a tension until it was diffused.

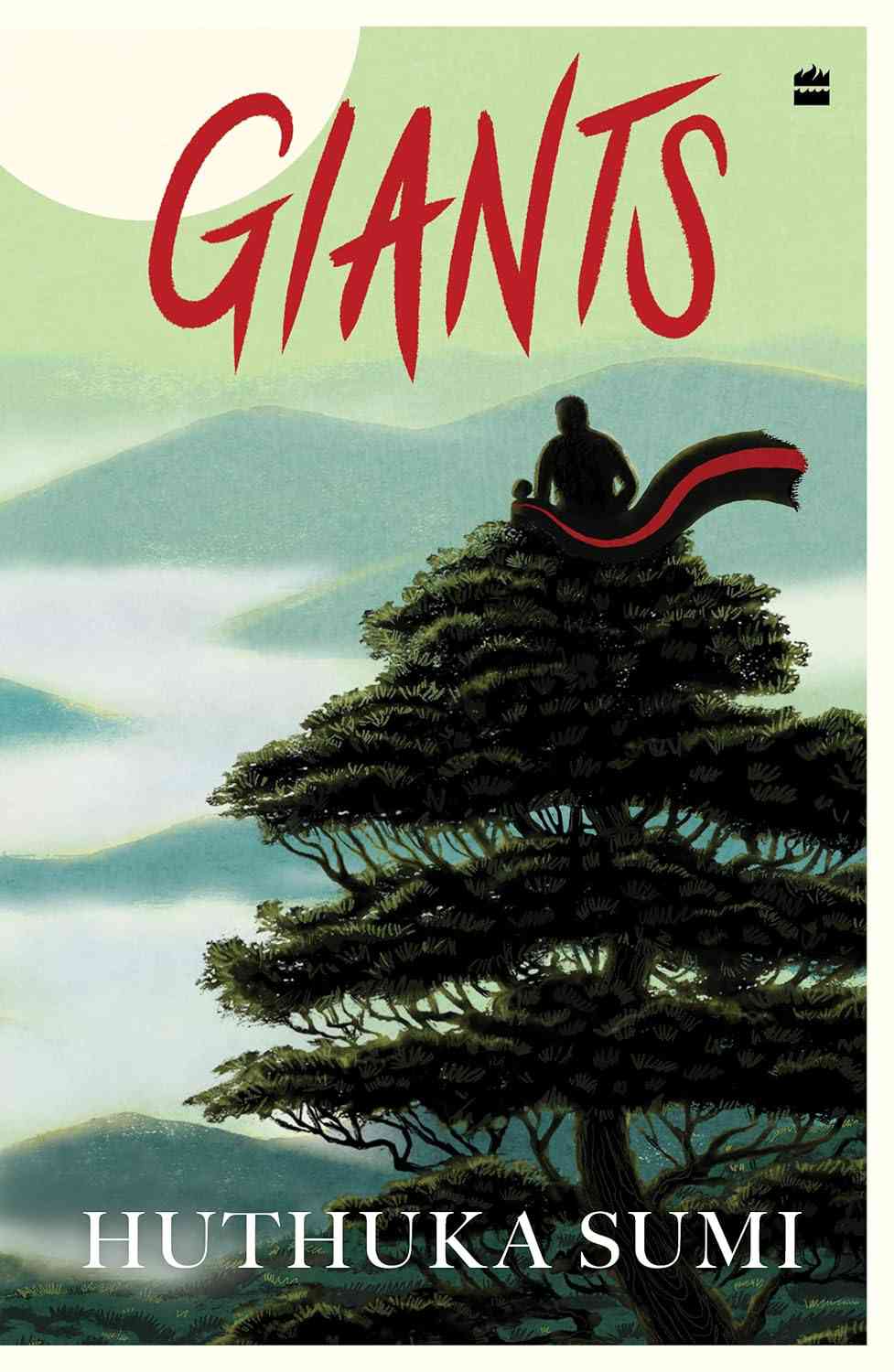

Excerpted with permission from Giants, Huthuka Sumi, illustrated by Canato Jimo, HarperCollins India.