A few years ago, I visited the Narayan Koti complex, a cluster of ancient temples located in a beautiful valley near Kedarnath, in Uttarakhand. The guide explained that the temples came into existence because of the Pandavas. “Pandavo ne banaye the (the Pandavas built them),” he said. In the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata, Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna, Nakula, and Sahadeva are five brothers collectively referred to as Pandavas, the sons of the king Pandu. In India, when no one really knows who built a temple, when it is not the charity or the order of some kingdom or a king, when it is the collective effort of people, it is common to attribute it to the Pandavas. Woh Nakula hai ya Bhima hai, maloom nahi, lekin jaise har ek ungli muthi ki takat banti hai, waise har ghar, har parivar ke contribution se yeh bane hai (no one knows if it is Nakula or Bhima. But just as every finger contributes to the strength of a fist, every household, every family has made these possible.)

Indian food is pretty much the same. The recipes do not belong to one chef, one kitchen, or even one ingredient, but they are built by constant innovations, small and big contributions, by mothers and grandmothers who ruled over and toiled in the kitchen, who kept not just the fires and food warm but even our hearts. And what better way to pay an ode to them than to cook just like them. Just a little bit like them at least. Therefore, use this book wisely, and remember that the recipes do not make a dish, you make it. More importantly, your fearlessness to give a part of you to it makes the dish.

I have two paintings from Tabo Monastery, the oldest surviving Thangka school, in Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, in my office. One depicts Manjushri, the Buddha of wisdom, and the other, Avalokiteshvara, the Buddha of compassion. “Without both in equal amounts,” the lama at Tabo had told me, “you cannot have real power.” The power of every dish, too, comes from the mix of wisdom and compassion – wisdom to tweak temperatures, ingredients, and even the style of cooking based on the ritu (season) and the compassion to serve, uplift, and contribute without expecting anything in return, let alone credit or recognition.

There truly lies the power of the seemingly simple khichdi, a one-pot dish of rice and pulses. This reminds me of the lyrics of a popular Hindi song “Jag ghoomeya thaare jaisa na koi” (I roamed the entire world but I could not find anyone like you). This feeling comes from the fact that the dish carries the wisdom and the compassion of so many who have lived before us.

This book aspires to help you explore the full potential of something as simple as khichdi by cooking it at home and not having it delivered to you from a cloud kitchen. It aims to remind you of the forgotten wisdom of eating in sync with the seasons. The hope is that you will live life to its fullest by celebrating seasons, ingredients, and your kitchen, while building a robust appetite to devour every experience of life.

Rice pej

It is a drink, it is a meal, it is just rice pej. If I was smart, I would say it is the prebiotic infusion you need.

Seasonal drink | Serves 2 | Prep 10 minutes | Cook 20 minutes

Ingredients

40g (11⁄2oz) rice (hand-pounded or single-polished or any variety available at home)

A pinch of hing (asafoetida)

Kala namak (black salt) to taste

2 tsp ghee

Method

Soak the rice in water for a few minutes. Drain and discard the water.

In a pressure cooker, bring 900ml (1½ pints) of water to the boil. Add the soaked rice along with hing and kala namak.

Close the lid and bring to full pressure over medium heat for 20 minutes, or until the rice is tender. Adjust the cooking time based on the type of rice you are using. One of my colleagues uses ukde tandul (Goan rice) and adds kali mirch (black pepper powder) in the pressure cooker for an extra kick, but I enjoy my pej plain, as given in this recipe.

Remove from heat and let the pressure release naturally, then open the cooker and add ghee, stirring gently to combine.

Pour it into a glass or bowl and slurp.

Aam ras and puri

The perfect meal to celebrate mango, the king of fruits.

Seasonal special | Serves 3 | Prep 1 hour | Cook 20 minutes, plus 1 hour of resting | Special equipment chakla–belan (rolling pin and board) and kadhai.

For aam ras

2 ripe mangoes, soaked in water for 20–30 minutes

For puri

120g (41⁄4oz) wheat flour

1 tsp semolina

½ tsp sugar

1 tsp salt

500ml (17fl oz) oil, of which 2 tsp is for the dough

Method

For the aam ras, trim off the top part of the soaked mangoes where the stem is attached. Then, gently press the mangoes from all sides to soften them evenly. Once they are tender, extract the pulp by gently squeezing from the bottom upwards, allowing the juicy flesh to release. Set this aside while you make the puris.

For the puris, in a bowl, combine wheat flour, semolina, sugar, salt, and 2 teaspoons of oil. Mix well. Gradually add water, kneading into a firm, elastic dough. Cover with a cotton cloth and let it rest for 1 hour.

Once rested, pinch off small portions of dough and shape into smooth balls. Using a chakla–belan, roll each ball into a thin circle.

Heat the remaining oil in a kadhai on medium heat for a few minutes. If it is not hot enough, the puris will absorb excess oil and turn soggy. To test the oil, drop a tiny piece of the dough in – it should sizzle and rise to the surface immediately.

Carefully fry the puris in batches of 2–3, until they puff up and turn golden-brown on both sides. Drain and place on a plate.

Enjoy hot, crispy puris with a generous portion of aam ras.

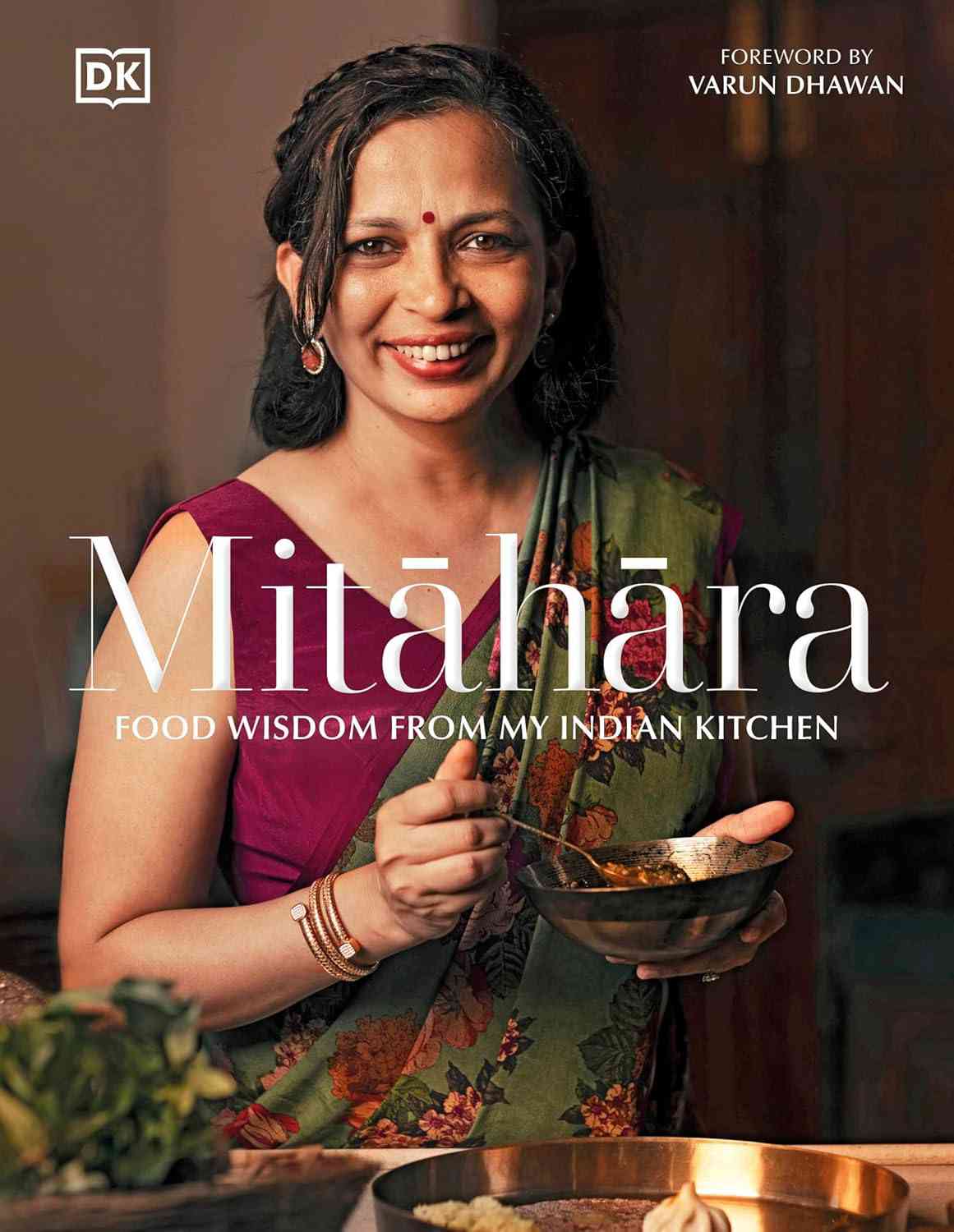

Excerpted with permission from Mitāhāra: Food Wisdom From My Indian Kitchen, Rujuta Diwekar, DK India Publishing.