I was fortunate in the relationships I developed with many of my teachers, especially two senior lecturers who were in charge of the drama society. In our first year, both my roommate Madhu Chopra and I got involved with the drama society. This was an involvement that dominated my three years in college and after, to the extent that I seriously wanted to become a professional theatre artist. It was through my activity in the drama society that I developed a close relationship with the two kind and protective teachers most responsible for its functioning, in whom I would confide my childish fears and dreams. Both taught in the English Department.

The first was Krishna Essauloff and the other was Lola Chatterjee. Mrs E, as she was known then, was tall, dark, imposing, a chain smoker, caustic, sarcastic, and harsh in her criticisms and equally generous in her praise. It was she who was the driving force behind the society. She was an unconventional woman, and what attracted us to her was the complete absence of a judgmental attitude towards the sometimes foolish antics of her flock in the drama society. In those days, we were not allowed to wear trousers to class. So, we used to wear them under long skirts, and as soon as classes were over, we would bound into the auditorium and fling off our skirts, much to the amusement of Mrs E.

She was a disciplinarian about the rehearsals, and young men who used to come to our play readings, ostensibly to audition for parts, but actually to get to know the girls, were shown the door soon enough. She had a beautiful reading voice, and sometimes when we were tired, Mrs E would pull out a book of plays and read out her favourite extracts to us. Mrs Chatterjee was easily accessible and demonstrative in her affection. She opened her home to me, taking me to concerts and plays outside of college. I remained in touch with her for many years. She was a strong support for me through my years in college.

For too brief a time, perhaps just a term, I was taught economics by Devaki Srinivasan (now Devaki Jain), who had recently joined the college. She made a big impression on me with her passion and articulation, and I still remember the anger with which she spoke about the inequalities of the Indian economy. I met her decades later when she was chairing a women's meeting, identifying herself firmly with women's struggles. Another person whom I learnt to respect was our sports coach, Ms Dhillon. A gruff and no-nonsense exterior hid her warm and generous heart. She was always concerned about the health and well-being of her “team”. I was then a member of the Miranda House (MH) Athletics team. Although, alas, I brought no laurels to the college, I did enjoy our practice sessions under her eagle eye! I relate later in this, remembering my experience at the university sports day – when once again, Ms Dhillon was there rooting for us! My own experience underlines the important influence teachers have on their students. I hope that this tradition of nurturing and encouraging young women and helping them to “grow up” without patronising them continues.

I’m not sure how important the drama society is in the lives of students at the college today. In those days, the college plays were a great event, and the hall used to be jam-packed on all three days that the show was produced. If MH girls were acting in plays in other colleges, one could be sure of the support from a big group of girls from the college who would be there on opening night. It was the same with those who were part of the debating society. We would all go in big groups to cheer them on. Students took an active part in the different societies of the college. This developed quite a feeling of solidarity. We were mainly competing against the men;s colleges. The feeling that we had to do better than them was quite strong. When we used to act in St Stephen’s plays, we would make it quite clear that it had to be a quid pro quo for our drama society. Once the exam results were out, there were always comparisons as to whether we had done better than the men’s colleges or not. As students, we used to get into heated arguments against the assumption that men’s colleges were better. I remember how, in a group discussion about making St Stephen’s or MH co-ed, the MH girls participating were unanimous in their opposition to the proposal as far as MH was concerned.

There were cases of sexual harassment on the campus. We were always warned by our seniors not to go walking on the ridge, as there were frequent cases of assault in the isolated lanes. My worst experience with such harassment was during university athletics, when I was representing the college in the 50 and 100-metre races. I was quite miserable, having been disqualified in the 50m for jumping the gun three times in a row, which, I was told later, was a record in the University! The humiliating walk off the field in front of a huge crowd was probably the longest walk I have ever had to take, but fortunately, there were quite a number of MH students there along with Ms Dhillon. We were in a group just outside the university grounds gate when we were surrounded by a bigger group of hoodlums who started pushing themselves on us, specifically calling out my name. Our only thought was how to escape, and we did manage to get to our gates safely.

Today, women’s struggles on campus have ensured that such an incident would not go unnoticed and that the victims themselves, unlike us, would raise a protest to ensure punishment for those guilty. This is a result of women’s movements and actions by democratic student organisations. There is also a much greater awareness of legal rights now. On that occasion, although there were a lot of talks that night in the hostel about it, we did not take any action, and indeed, we did not really know what action we could take since we did not recognise any of them. I appreciate the big development of consciousness on these issues when I see large numbers of female students from MH and other colleges joining demonstrations against cases of sexual assault, often leading to militant slogan shouting.

Another area in which there has been a most welcome change is the abolition of the Miss Fresher contest. This was one of the many “traditions” of the college. It was a mandatory parade of all the freshers dressed up to the teeth before a huge crowd of yelling, cheering students of the college. In my second year, when I was one of the judges, I was acutely conscious of the trauma of the experience for so many of the girls who hated it. The results of the MH Miss Fresher contest were a source of interest among some of the male students on the campus. When I happened to have been the person selected in my first year, walking around the campus was sometimes a horrible experience because I heard the most objectionable comments. I was happy when, several years later, by which time I had joined the Students Federation in Calcutta in the thick of the students' movement, having enrolled as a casual student in the university there, I heard that the MH union had ended this tradition. I am sometimes asked how I could have been part of such a contest. The simple truth is that, at the age of 16, I did not know better.

At the end of my second year, a tragedy occurred, which had the biggest impact on all of us in the hostel. It brought us face-to-face with violent jealousy and the reality of a woman as a belonging, as property to be destroyed if she could not be possessed. Our group of close friends consisted of about seven or eight of us. Juhi and Sudha shared a room, then Renu and Sushma, who were roommates, Madhu and me, and there was also Sara, who shared a room with her younger sister. We were all from different backgrounds and different parts of the country, and though each of us did have friends outside the circle, in the hostel, we spent a lot of time together. Sushma was also on the athletic team. She was good at the shot put and javelin. Perhaps it was because of that talent that she came to be called “Shot”. It was a name that would haunt us for several years. Tall, well-built, with a radiant smile and deep dimples – I can see her so clearly, even today.

She was popular in the hostel, and we always knew of her arrival because we could hear her singing far down the corridor. Sushma was in the process of getting out of an engagement with someone much older than her. I cannot recall now whether the engagement was with the approval of her parents or otherwise. She had tried to break it off on several occasions but would be persuaded by him to get back together. Finally, she wrote to him and said that she did not want to see him again. She read out the letter for our approval. Several months passed. He was in the army, posted quite far away from Delhi. I remember the long talks we had and the sense of relief in her that it was over. One day, Sushma got a letter from him saying that he wanted to meet her to return her letters. She told us about it. All of us were against her going; we tried to persuade her, but she said she did not want to hurt him, and anyway, she wanted her letters back. I think it was Renu who volunteered to get them for her since she knew him. Sushma refused. “I can’t be so cruel,” she said.

There was nothing we could say or do to make her budge.

Madhu and I left for her cousin’s house, where we were to spend the night. It was the last time we saw Sushma alive. We got a message late that night. Sushma had gone to the university café to meet him. Barely had she sat down when he shot her through the head. He then turned the gun on himself and fired. He died instantaneously. Sushma was taken to the hospital, but she did not survive the night.

The next few days are blurred in my memory. We returned to the hostel. Everywhere there were groups of shocked, crying girls – Shot has been shot – whispers, sobbing. We sat huddled outside what used to be her room. Nobody wanted to leave. The hostel and college authorities were extremely sympathetic. We were called in by the principal, and she spoke kind words to console us. The hostel made arrangements to take us to her funeral. The family had requested that only a few of us go. We said goodbye to Shot, laid down on a cold block of ice.

But the college got bad press. The sensational way it was reported upset all of us greatly. It was our first experience of something like that. It became a matter of gossip and speculation. The attitude of the University union was also reported to be extremely negative, blaming the college for laxity. For a while, the rules at the hostel got stricter. Visitors were more carefully screened. Gate passes were checked repeatedly. Soon, however, things got back to normal. But not for us. Everything changed after that. We felt restless and depressed. We tried to make sense of all that had happened and why. We were beset with guilt. Could we not have saved her had we prevented her from going?

Quite broken in spirit, we all left for the holidays. It was fortunate for all of us that we could go home. I came back in July 1965 as a final-year student. My younger sister, Radha, joined college that year, which made the term bearable. There were new faces and new experiences, which kept us busy and diverted us.

That year was also dominated by the Indo-Pak War. The security of the girls in the hostel was of great concern to the college authorities. Meetings were held with the principal, the warden, and the union representatives. In an emergency general body meeting, we were told that those who had local guardians to stay with could temporarily shift outside the hostel. Ms Dhillon set up a drill for the rest of us. Volunteers to patrol the hostel in groups of eight or ten were asked for. There was no dearth of them. We felt that we were playing a very important role. Every night, eight or ten girls would walk up and down the corridors. It may have served little purpose, but the girls took great pride in contributing to the “war effort.” Strict instructions were given that as soon as there was an air raid siren, everyone had to rush down to the ground floor, where we were all assigned rooms. But a sense of the kind of jingoism raging outside came in the form of the “Pakistani spy”.

One day, there was a rumour that a Pakistani spy had been caught quite near our hostel and that the police had apprehended a tall, fair man with light eyes. Embellished versions of the story spread like wildfire. We heard that students were roaming around the campus looking for others in his gang. When we asked some of the lecturers about it, they said it was just a rumour. Perhaps it was part of a motivated campaign. Today, facing the onslaught of communal propaganda and the use of religion for narrow political ends, I wonder whether it was because there were no communal currents in the hostel at that time or because we were so politically naïve that we did not know what was happening. We were completely isolated from it. The other aspect is that there were hardly any minority community students in the hostel, and we never directly faced the issue of minority baiting, which one learnt was taking place elsewhere in the city.

The year was spent catching up on academics. We were also preoccupied with what we were going to do after college. In those days, joining the IAS was a popular idea. Some wanted to teach. I remember some of the students being quite resigned to the idea of getting married right after graduation. Indeed, there were quite a few engagements we had celebrated during the last term. As for me, I was as yet undecided but strongly drawn to a career in theatre, following the dream that had been born in me on that dusty Miranda House stage. It is a different story that life and events took me in a totally different direction.

I sometimes visit MH and meet with the students, who are conscious, articulate, and so much more aware of the world, their place in it, and how they would like to change it than we ever were. I am so happy to see this fundamental change. In the corridors I pass through on these occasional visits, in my mind’s eye, I see the shadows of that young group of women, their arms slung together, absorbed in talk and laughter, unaware of the impermanence of that feeling of freedom.

Brinda Karat is a member of the Polit Bureau of the CPI (M). She has worked in various capacities in over half a century of involvement in struggles for social change as an office bearer in trade unions, as the General Secretary of the All India Democratic Women's Association, as Vice President of the Adivasi Adhikar Rashtriya Manch, and as a Member of the Rajya Sabha.

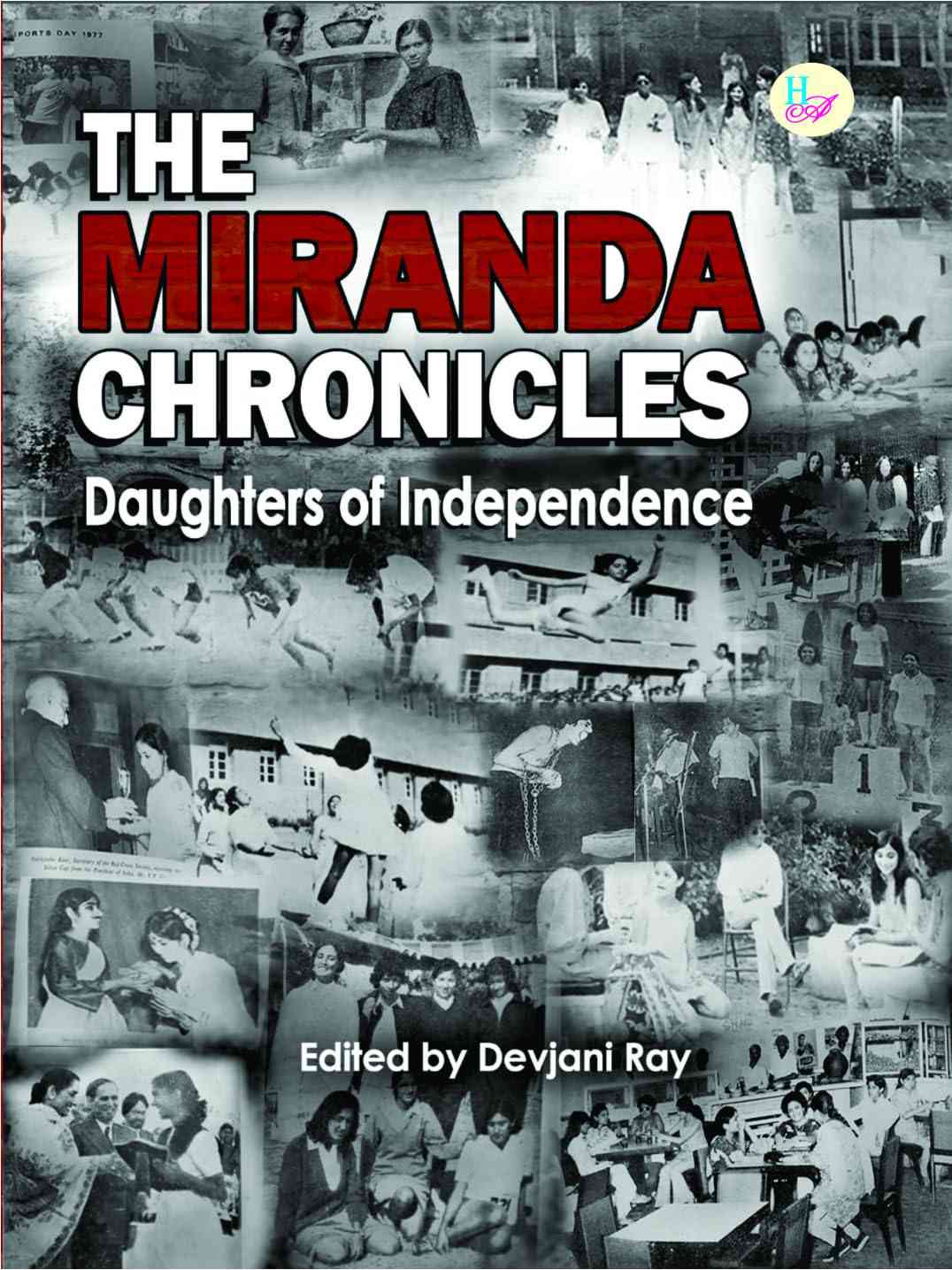

Excerpted with permission from ‘A Personal Remembering’, Brinda Karat in The Miranda Chronicles: Daughters of Independence, edited by Devjani Ray, Har-Anand Publications.