The Election Commission was for seven decades the paramount arbiter and defender of India’s universal suffrage, trusted widely by millions of Indian voters. Its credibility, however, has been mortally dented in the last decade.

Yet even by the commission’s now severely diminished standards, it hit a new low with its abrupt and precipitous decision to undertake a “special intensive revision” of the electoral rolls of the state of Bihar. Even though the rolls were reviewed as recently as January 2025, it prescribed, with just months left for the polls, an unprecedented process that required at least 29 out of nearly 79 million Bihari voters to prove that they and in many cases their parents were Indian citizens.

This has thrust millions precipitously into the sudden dread of targeted disenfranchisement and statelessness, of detention centres and forced expulsion from the country of their birth.

These orders of the Election Commission not just break precedent but also the constitutional boundaries to its authority that are laid down in the law and repeatedly clarified and reiterated by the courts. The first of these are the principles that the Election Commission is authorised to investigate and verify a voter’s identity but not her citizenship, that if a person’s name is on an electoral list the presumption of the Election Commission must be that she is a citizen, and in case the EC suspects that she is not a citizen, the burden to prove this lies with the commission and not with the individual.

Instead, those residents of Bihar who were born before July 1, 1987, are required to present evidence of their birth and place of birth. Those born between July 1, 1987 and December 2, 2004, are mandated by the commission to submit documents of their own birth and that of one parent. Those born after December 2, 2004 have to submit proof of their own birth and that of both parents. They are to prove this with vintage documents that few possess, and that too in the impossible time frame of one month.

Does the Election Commission have the authority to investigate a voter’s citizenship? The Supreme Court has consistently and unambiguously maintained that it does not. When a person applies to be included in the electoral rolls, all she is required to submit to the official is a self-declaration that she is a citizen. It has also clarified that if a person’s name is already on the voters’ list, the person must be presumed to be eligible to vote, and a citizen.

It has made clear that investigating, certifying or issuing orders about citizenship, including deportations, all lie in the domain of the home ministry and no other agency including the Election Commission has this authority. And it places the onus of proving otherwise in situations where there were reasons to question the eligibility of the voter on the election authorities.

The questions of citizenship and the powers of the Election Commission were carefully considered by a three-judge bench headed by the Chief Justice of India AM Ahmad in 1995 in the landmark case Lal Babu Hussein and Others vs Electoral Registration Officer and Others. The dispute arose after the Election Commission called upon residents in some constituencies in Mumbai and Delhi to provide evidence that they were Indian citizens. In September 1994 it ordered Electoral Registration Officers to identify, declare and delete the names of foreign nationals.

This resulted in summons by the Mumbai police to 1.67 lakh residents living in the jurisdiction of 39 police stations to prove their citizenship. The only documents that the Election Commission would recognise for this were birth certificates, passports issued by the Government of India, certificates of citizenship, or entries made in the register of citizenship by the Government of India.

In a city still healing from the communal divide by the Mumbai riots of 1992-’93 in the wake of the demolition of the Babri Masjid, this was seen then – as it is now – as part of a plan to harass and disenfranchise the minority Muslim community.

A similar drive began also in Delhi. Muslim slum residents in Motia Khan, Paharganj, New Delhi, in their writ petition in the Supreme Court, testified to be migrants from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar who came to Delhi in search of livelihood and who had lived in that area for many years.

They did not have the documents that the Election Commission had demanded from them, but they had ration cards, copies of past electoral rolls that bore their names and school records that established them to be inhabitants of that locality.

Residents of another Delhi slum Sanjay Amar Jhuggi Jhompri colony in the Matia Mahal constituency of Delhi also petitioned that they too were migrants from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar who had been voters in the area for over a decade. Even so, the election officials suspected that they were foreigners and required them to furnish documents to prove their citizenship. They rejected their ration cards and identity cards issued by the Delhi Administration. As a result, out of the 18,000 voters in the slums, the names of only 300 figured in the revised electoral roll.

Opposition MPs continued to demonstrate against @ECISVEEP SIR electoral revision in Bihar.@INCIndia @RahulGandhi pic.twitter.com/9om35CMzc3

— Dr Md Jawaid (@DrMdJawaid1) July 28, 2025

The court struck down all these proceedings that the authorities had launched against persons they suspected to be foreign nationals, and reiterated the principle that only the Centre is empowered to investigate citizenship.

In keeping with this 1995 judgement, the Election Commission, until now, accepted just a self-declaration that a person is a citizen as adequate proof of citizenship. If the Election Commission had reason to believe that the declaration is false, it could collect evidence and give notice for furnishing a false declaration, but it could not investigate citizenship.

This principle was again reiterated by the Supreme Court while hearing petitions challenging the Special Intensive Revision of voter rolls in Bihar, that the Election Commission cannot investigate citizenship, only confirm the identity of the person.

The Special Intensive Revision, however, defies these rulings. As the court had explained, if a person’s name is already entered in the voters’ lists, the Election Commission must presume that before entering a person’s name, the official must have gone through the procedural requirements under the statute.

Instead, without basis in law, the Election Commission now denies to all those whose names were on electoral rolls after 2003 the benefit of this presumption that they are citizens and eligible voters. In effect, it strikes them all off the electoral rolls and shifts the burden to them to prove with prescribed documents that they, one parent or both parents are Indian citizens. It invents its own parallel system to conduct a mass investigation into a person’s citizenship.

In an explainer in The Wire, Pavan Korada explains this to be a fundamental jurisdictional error. Through the Special Intensive Revision, the Election Commission has “imposed a new condition for voters to remain on the rolls – a retrospective re-verification of documents based on an arbitrary 2003 cut-off”.

It does not have the authority to do this in the Representation of People Act, 1950. “This is not a procedural clarification; it is … a legislative act the ECI is constitutionally forbidden from making.”

By doing this, the Election Commission has not just thrust millions of impoverished working people in Bihar into sudden and avoidable turmoil. It also in effect is calling to question the work of the commission since 2003. After all, the last summary revision of the Bihar electoral rolls was completed as recently as in January 2025.

How then did the commission suddenly discover so many flaws to justify this drastic intensive revision and that too just months before when the state elections were to be held? Voters have cast their votes in five state elections and five general elections since 2003. Is the Election Commission saying now that it has suddenly discovered that significant numbers of persons who voted in all these elections were ineligible, and possibly foreigners?

This is not simply a case of overreach by a public authority with good intentions. There is much reason to believe that the Election Commission has defied the limits laid down by the Constitution, the law and the Supreme Court to fulfil the political agenda of the ruling establishment.

To begin with, its sudden “discovery” of masses of illegal immigrants in Bihar from Bangladesh, Myanmar and Nepal is articulated in a discourse that closely echoes the campaign in all BJP-ruled states, especially since the Pahalgam terror attack, against alleged Bangladeshi illegal immigrants and Rohingyas. Bengali-speaking Muslims are being rounded up, thrown into detention centres, pushed across the border with Bangladesh at gunpoint, or even thrown into the sea.

Human Rights Watch documents in this period this forced expulsion by Indian authorities of hundreds of Bengali Muslims – many of them Indian citizens from border states – to Bangladesh. This is being done without due process, labelling them “illegal immigrants”.

“India’s ruling BJP is fuelling discrimination by arbitrarily expelling Bengali Muslims from the country, including Indian citizens,” says Elaine Pearson, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. The Indian government has provided no official data on the number of people expelled, but the Border Guard Bangladesh has reported that India expelled more than 1,500 Muslim men, women, and children to Bangladesh between May 7 and June 15, including about 100 Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.

In a notably similar tenor, in justifying its Special Intensive Revision the Election Commission said that it had reports of large-scale illegal immigration from Nepal, Myanmar and Bangladesh into Bihar. This is surprising because in 2019, the Election Commission had reported to parliament that it had found no instances of “foreign nationals” on electoral rolls in 2016, 2017, and 2018, and only three cases in 2019.

After the process of the Special Intensive Revision was underway, the Election Commission announced that booth level officers in Bihar had found people from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Myanmar during house-to-house surveys, and that their names would not be included in the final electoral roll after inquiry. But when asked for details of the numbers of “foreign illegal immigrants” or the locations where they were found in Bihar, an EC spokesperson said tersely, “No details yet”.

Even more directly pertinent to the electoral prospects of the BJP in the coming elections is the targeted disenfranchisement that is feared of voters from communities that are unlikely to vote for the BJP, especially Muslims.

Debasish Roy Chowdhury, senior journalist and co-author of To Kill A Democracy: India’s Passage to Despotism, points to the results of the last Bihar election of 2020. The opposition alliance of the Mahagathbandhan got just 0.03% votes less than the National Democratic Alliance: a difference of a mere 12,768 votes. In 11 crucial seats, the winning margin was less than 1,000 votes. In one seat it was 12.

Dipankar Bhattacharya, general secretary of the Communist Party of India- Marxist–Leninist Liberation, observes that if as a result of the Special Intensive Revision even just 3% names are deleted from the electoral rolls in Bihar, this would mean roughly 10,000 voters being dropped on an average in each constituency. This would have the potential to change the election result in constituencies with narrow vote margins in favour of the BJP-led alliance.

This sudden deployment by the Election Commission of what should be a legitimate on-going process of cleansing electoral rolls of people who have died, or migrated, or are otherwise ineligible, has resulted predictably in a great deal of what has been aptly described as “last-mile chaos”. The task the Election Commission set for itself was impossible to accomplish in the period of just a month. This led to repeatedly changing goalposts, confusion both among field officers and residents, the refusal of the EC to field questions in open press conferences, and mounting bewilderment and alarm among Bihari residents and migrants.

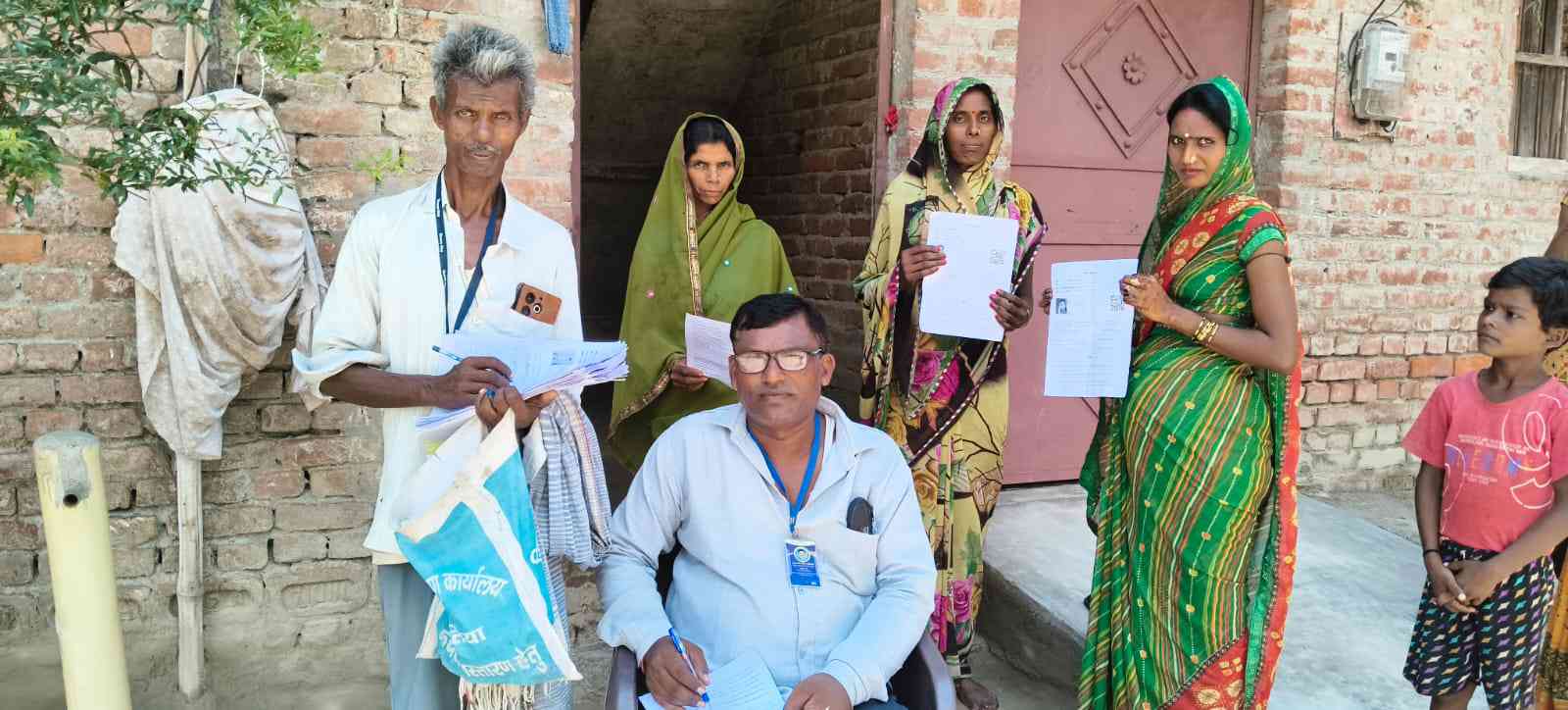

The initial plan was for election officials to go house-to-house and to help residents fill their forms in duplicate and collect their photographs and documents. This gave way to people being asked to meet the officer in their offices and camp-offices, to just single forms being distributed, to accepting forms even without the necessary photos and documents (but without explaining what the fate of such forms that were not accompanied by documents proving citizenship).

As criticism mounted, the Election Commission’s claims of progress became increasingly improbable. For instance, the Election Commission claimed that 1.18 crore forms had been collected in one day. This would mean that 137 forms were collected every second for 24 hours.

Observers fear that the Special Intensive Revision might result in the disenfranchisement of as many as 20 million voters. Most in danger are migrant workers. Workers from Bihar toil in the farthest corners of the country, making bricks, erecting highways, dams and high-rise buildings, serving in eateries and homes and in farms in Punjab and Haryana.

Estimates of their numbers vary from 10 to 20 million. Many of them are known to value their voting right enough to sacrifice a few days’ wages and spend the fare to their homes only to cast their vote. But how many of them would be able to afford the costs of travelling home and collecting documents only to ensure that their names appear in the electoral rolls? Theoretically, they have the right to file their forms and documents online. But this presumes first that they would be carrying their birth documents and those of their parents, which is very unlikely, and that they would have the time and resources to upload these in a cyber-café.

However, even graver than the danger to India’s democracy of a stolen election in Bihar are the clear signs that the Election Commission is initiating an “NRC process through the backdoor”, as many political leaders have alleged. These worries are further compounded with the ominous announcement by the Election Commission that the same process of intensive revisions of electoral rolls will be repeated throughout the country.

The NRC, or National Register of Citizens, was updated for Assam by the home ministry over six years from 2013-’19, supervised by the Supreme Court. As with the Special Intensive Revision initiated in Bihar by the Election Commission, what made the NRC process in Assam such an intolerable burden on the population in Assam was the shifting of the burden of proving citizenship to the individual through a series of vintage documents like birth and school certificates. This meant that the state abandoned the presumption that every resident was a legal citizen. Instead, each resident was in the eyes of the state potentially an illegal immigrant, and had to prove to the state that she was lawfully an Indian citizen.

This process engendered untold human suffering among millions of impoverished and unlettered citizens of the state, as they scrambled to collect decades-old documents in a country which had no tradition of registrations of births, marriages and deaths, and fought their cases before often openly hostile and prejudiced tribunals. We have described this tumult of human suffering caused by the targeted manufacture of statelessness in our book This Land is Mine, I am Not of This Land, which I co-edited with Navsharan Singh.

The Centre had announced in 2019 its resolve to create a National Indian Register of Citizens, only after Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, which created a legal presumption for undocumented people of religious identities other than Muslim that they were persecuted minorities from neighbouring countries, thereby fast-tracking their right to Indian citizenship.

The open discrimination of this law against people of Muslim identity that flew in the face of India’s constitutional guarantees. This ignited the largest non-violent nationwide protest that free India has seen in which people of all faiths joined. This protest, lasting a hundred days, was cut short by the covid-19 pandemic. For the five years since, it seemed that the union government had quietly shelved its perilous plan of initiating a nation-wide NRC.

But the Special Intensive Revision, worryingly patterned after the Assam NRC, seems a pointer to the Election Commission front-ending a national NRC, undeterred by the fact that this is outside its constitutional jurisdiction, and the massive opposition to this exercise by all sections of the Indian people and the entire political opposition.

Whereas in Assam, 33 million people were mandated to prove their citizenship in this way in a process that lasted six years, the Election Commission required at least 29 million people (the estimated number of people who became adults in Bihar after 2003) to accomplish this in just one month.

One of the collateral dangers of the citizenship imbroglio in Assam is already visible in the Special Intensive Revision process in Bihar. Even prior to the NRC, relatively junior officials were empowered to mark persons in the electoral rolls as “D-voters” meaning “doubtful voters”. This was done without following any due process of communicating in writing the reasons for their doubts to the person, and giving her a chance to prove she is a legal citizen. A similar power has been vested in middle- and junior-level officials to identify people who they for any reason consider to be of uncertain citizenship. This would be enough to withhold from them their most basic democratic right – the right to vote.

Memories of Assam have overwhelmed me ever since I learned that the Election Commission through the Special Intensive Revision was once again reversing the burden of proof, and requiring – outside its constitutional role – every Bihari adult to prove again through hard-to-access old documents that they were legal citizens of India.

In our years of work among them, my colleagues in the Karwan e Mohabbat and I struggled for the release of people incarcerated for long years in dehumanised detention centres that were in fact jails within jails. We encountered many tragic instances of terminal despair and suicide, of people who quietly hung themselves or jumped into a well in the dread of being declared a non-citizen.

In every election since India became a republic, it is working class Indians who form the longest lines to cast their vote. I often wonder at the irony that those who continue to hold the most robust hope in democracy are those whom democracy has most consistently failed: India’s impoverished and oppressed millions.

Their faith in democracy pivots on faith in the independence, fairness and integrity of the Election Commission. This faith has been steady and cynically dismantled through the past decade. In the past, members of the election commission were selected by a committee comprising the prime minister, the leader of the opposition, and the chief justice. This ensured that the election commissioner was not simply a nominee of the ruling government. But the Modi government overturned this by legislating that the members of the Election Commission would be chosen instead by a three-member panel comprising the prime minister, the home minister and the leader of the opposition. This means that the government will effectively choose the persons who would be charged with being fair umpires during elections.

Most recently, the Election Commission has done nothing to assure voters that the state elections held in November 2024 in Maharashtra were not stolen. It has not explained how 4.1 million voters could be added to Maharashtra’s electoral rolls in just five months, more than the numbers added in five years, nor the discrepancy of 7.6 million votes in final turnout figures. As Debasis Roy observes, “These are not minor aberrations; even a fraction of these numbers is enough to swing elections” .

However, its decision to require 89 million voters in Bihar to prove that they are Indians within a month shortly before the state elections has plummeted the reputation of the EC lower than it has ever been. The opposition parties had gone to the Election Commission to protest the intensive revision of electoral rolls before the coming Bihar election, which the opposition believes to be a clear conspiracy to disenfranchise Bihar voters. “After meeting the Election Commission”, Khera said to the press after the meeting, “we realised we had gone to the wrong address. The Commission doesn’t need its own building. The BJP has a huge headquarters, they should just take up a floor there.”

It was not just the political opposition. Social media exploded with sarcastic memes. My favourite was this one: “The Election Commission has denied all rumours that it has merged with the BJP. It is only extending outside support to it”.

History will judge India’s Election Commission very harshly for letting democracy die in India. Jagdeep Chhokar, founder of The Association for Democratic Reforms and one of India’s most trusted democracy activists reminds us, “The Indian electorate today may be poor, may be deprived of a lot of things, but everybody is fully aware of their right to vote. That is the only right some people believe they have”.

This question haunts me. On election day in Bihar this September, how many men and women are going to be turned away from the election booth because their names have been erased from the electoral rolls?

What then will remain of our already shrunken democracy?

I am grateful for the research support of Omair Khan.

Harsh Mander is a peace and justice worker, writer, teacher who leads the Karwan e Mohabbat, a people’s campaign to fight hate with radical love and solidarity. He teaches part-time at the South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University, and has authored many books, including Partitions of the Heart, Fatal Accidents of Birth and Looking Away.