“In case of danger… In case! But you couldn’t get away from danger! It was all about you, all the time.”

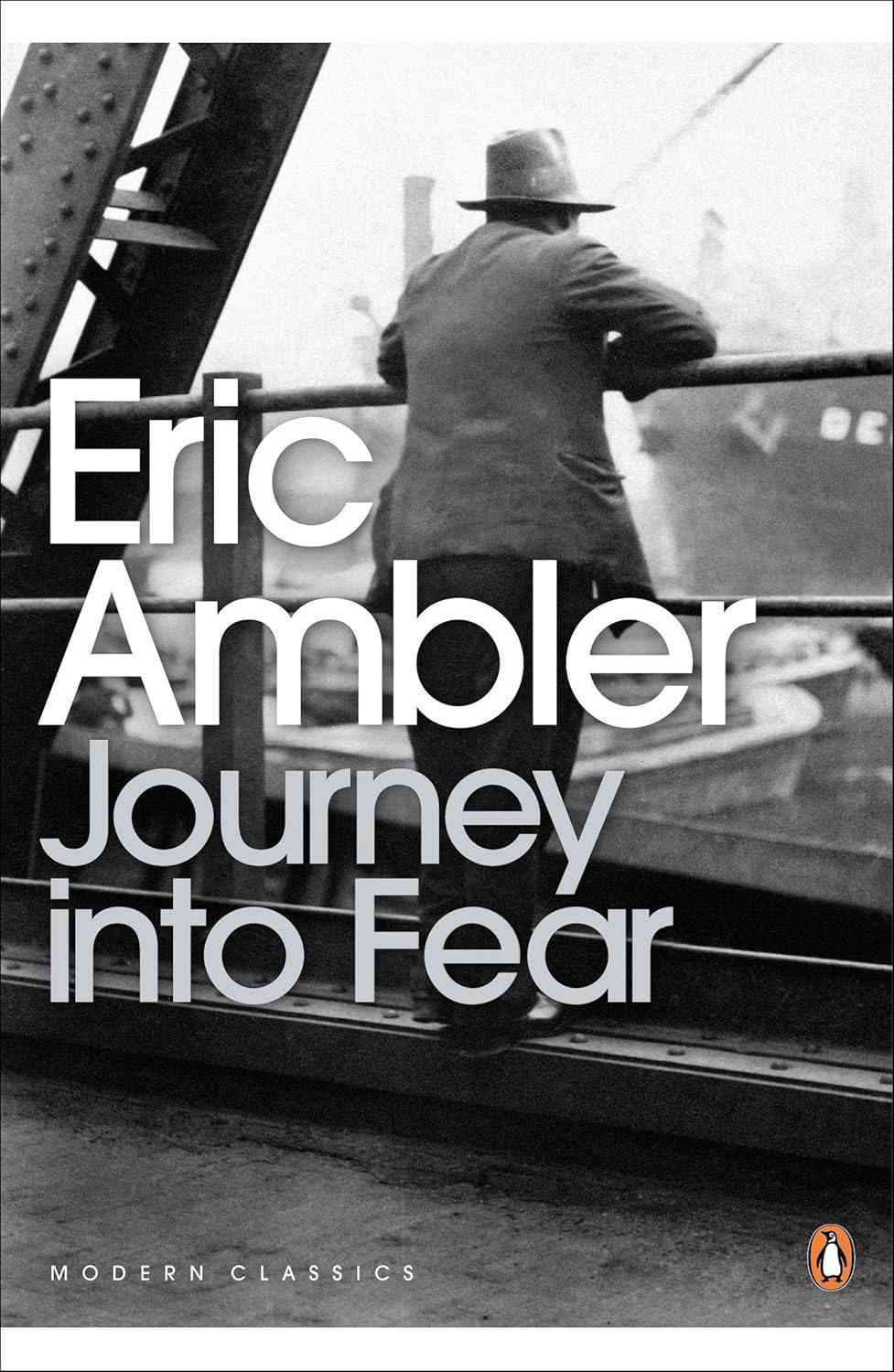

Published only a year into the Second World War, Eric Ambler’s 1940 spy thriller Journey into Fear foregrounds the fear of unknowability rather than the actual act of injury. This would have been true for most people during such a distressing time – the impending doom feels much bigger, sinister than the sporadic acts of violence they are subjected to. When death is fated, it is the cursed moments leading up to it that cause the most agony.

Graham has a “highly paid job” at Messrs Cator and Bliss, a “big” armaments manufacturing concern in England. Needless to say, even – especially – in troubled times, business is booming and he has been sent to Turkey on work. We first meet Graham on his final night in Istanbul as he prepares to leave for home on a train the next morning. Business successfully secured, his local companion, Kopeikin, takes him out for drinks and dancing at a city nightclub. Graham reluctantly agrees, citing an early start the next day. But he feels grateful for not turning down the offer when Kopeikin introduces him to Josette, the main attraction of the evening. A dancer, she and her husband/partner Jose, are also all set to sail to Paris the next morning. Initially taken in by her charm, Josette will become Graham’s confidante as he tries to elude his killer.

Chasing the killer

Returning to his hotel room, Graham finds an intruder, who shoots him but he escapes, with just a graze. What Graham mistakes for a botched burglary attempt is not so. The local intelligence chief, Colonel Haki, clarifies that it was an attempt to murder. The Germans want him dead – it’s the time of war, and the Turks buying British arms isn’t good news. Graham refuses to believe him – he’s just a man doing his job, he has no enemies, why would anyone want him dead? Naturally, the shot rattles him and for the first time, he truly comes to fear death. What he had taken for granted as a consequence of old age or some terrible illness had suddenly become real – so real, that he had almost touched it. But there is a delirious quality to Graham’s fear, and during a strange wartime, can anyone be trusted to speak the truth? The question, therefore, remains: Will Graham be killed?

He is advised to avoid the train and take Sestri Levante, a passenger steamer to Paris, from where it’d be arranged for him to depart for England. The steamer is hardly a haven – his fears are not eliminated but somewhat assuaged by the interesting company he finds onboard. There’s a Turkish businessman who sells cigarettes, an elderly German archaeologist, a quarrelling French couple, and of course, Jose and Josette who pose as Spaniards. The long days on the sea allow for hearty conversations and close observations. He warms up to Kuvetli, the Turkish businessman, engages in productive debates with Haller about civilisations and history, and flirts fruitfully with the beautiful Josette.

Patriotism in wartime

The steamer is a world unto itself with passengers of various nationalities rocking together on choppy waters. The tension of the war brings out the patriots in them and each of them is ready to defend their national pride. The most zealous amongst them are the French, who are loath to have a German amongst them. Haller insists he’s a “good German” and not deserving of their contempt. But as the threats of his murder persist, Graham reflects on the “business of death” – his personal fear versus the great tragedy of the war. For someone like him, who has much to profit by selling instruments of death, he coldly observes that “life and death” were at the mercy of “an elementary arrangement of springs and levers and a few grammes of lead and cordite.” Away from the theatrics of the ongoing war, the German contemplates the nature of patriotism – its futility and hypocrisy. He correctly points out that no one wishes to be killed and that patriotism in effect is a “ruling class [wishing] a people to do something which that people does not want to do.” It is not the common man who gains anything from cheering for war, but the banker who fills up his coffers no matter the outcome, the real war criminals. It is here that Ambler bluntly puts forth his anti-establishment views. There is no disillusionment about its ugliness even when you are on the winning side.

On the steamer, Graham is forced into exaggerated actions and reactions. With insufficient information imparted to him, Graham is in a constant state of high alert. Any unexplained occurrence takes the shape of mortal danger. Ambler is supremely stylish in devising the drama of Graham’s isolation. As the real identities of the passengers begin to emerge, once again Graham’s sanity comes into question. On the steamer, what were at first polite associations sour into imposing obligations, with each twist revealing maddening possibilities. What Ambler writes halfway through the book, “The essence of all good strategy is simplicity,” proves itself true when the journey – Graham and the novel’s – concludes.

Journey into Fear was adapted into a movie of the same name by Norman Foster and the inimitable Orson Welles in 1943, with some minor changes in the ending. Though not one of Orson Welles’s best, the movie does a convincing job of bringing Ambler’s extraordinary cast of characters to life.

Journey into Fear, Eric Ambler, Penguin Modern Classics.