We live in an era of breath-taking change in the way that we read, write and record things. Digital repositories replace paper records. Everywhere, the keyboard, mouse and trackpad seem to be rendering handwriting obsolete, even as voice-enabled transcription in turn offers new ways to generate text. The pen feels an increasingly strange object, as our fingers accustom themselves to other gestures: we swipe, tap, drag, toggle, use our thumbs.

Acute anxieties surround these shifts, as older forms of work and social connection dissolve, with unpredictable consequences for our mental and bodily health. How, we ask ourselves, should we measure our expanded access to knowledge and freedom of communication against their costs – huge concentrations of corporate wealth and opportunities for state control that have yet to be measured?

The challenges in this “knowledge economy” of our own times has striking historical precursors. From Elizabethan England to Mughal India, Safavid Persia to Ming China, the emergence of new practises of recording and documentation dramatically expanded the reach of states. Early modern scribal elites moved to exploit growing opportunities in state service, challenging older religious and political monopolies. In different forms, these shifts raised profound new questions about the government of the self. What did it mean for older hierarchies when the personal command of literate skills bestowed such advantages?

Understanding contemporary language politics

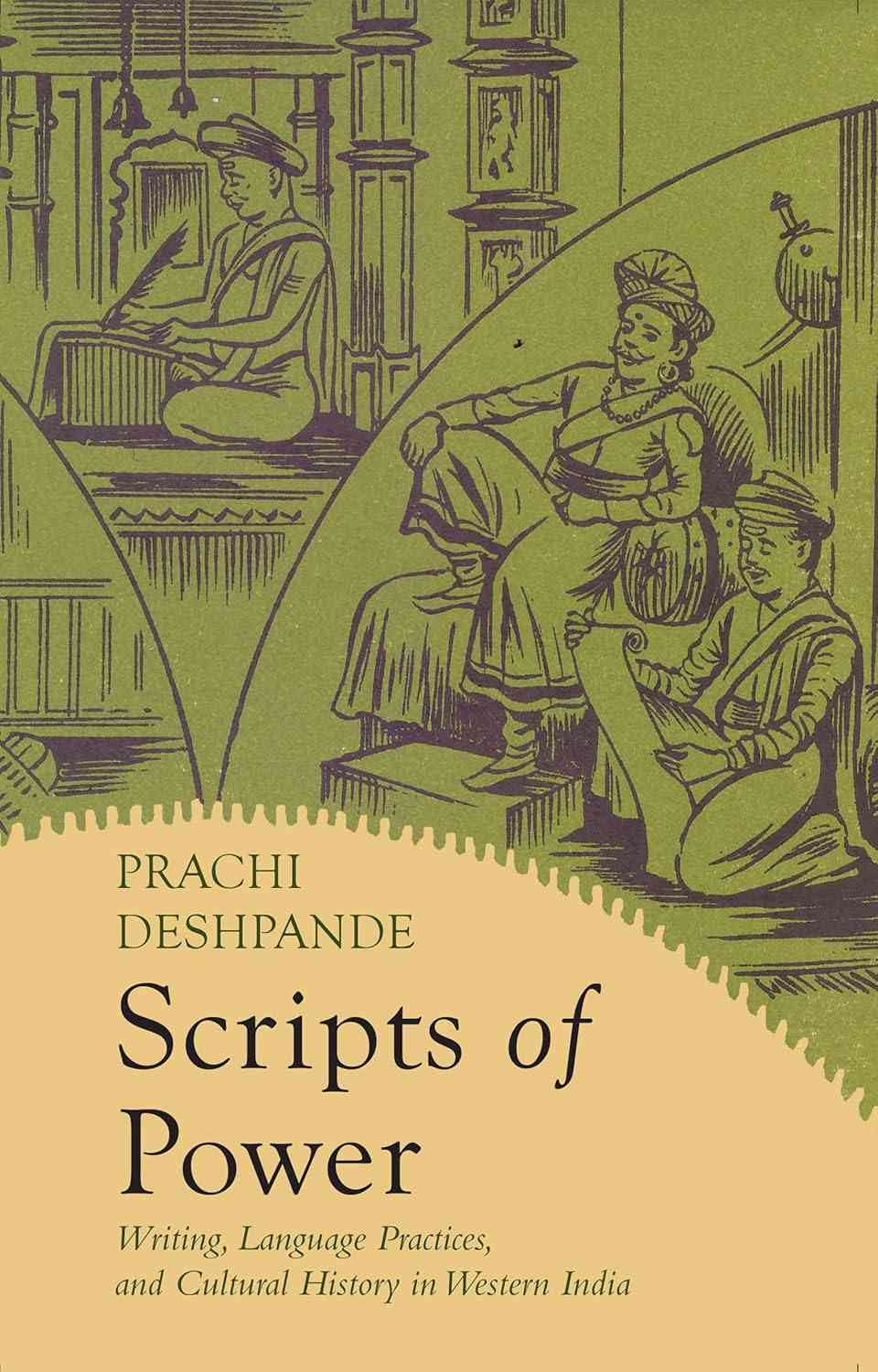

Prachi Deshpande takes up these themes in Scripts of Power: Writing, Language Practices, and Cultural History in Western India, her new cultural history of Modi, the cursive script of western India’s Marathi language. It resonates in striking ways with some of our own predicaments. The book also offers key insights into the controversies that continue to surround India’s regional languages. In Maharashtra’s history, of course, language contests have long played a particularly prominent role. The state government’s recent attempt to mandate Hindi as a third language in state-run primary schools has sparked protests and violence. Deshpande’s book, and the deep historical background that it offers, thus speaks to acute issues in India’s contemporary politics.

With its conjoined letter forms and abbreviated vowels, Modi script gained ground in the seventeenth century as a quick and efficient medium for clerkly writing about worldly and business matters. By contrast, Balbodh, the Marathi form of Devanagari script, retained its association with the ritual purities of Sanskrit, and the devoutness of Marathi bhakti poetry. However, Marathi’s assimilation of Mughal India’s Persianate bureaucratic forms also helped draw Modi into use within other vernaculars across the Maratha empire. In absorbing detail, Deshpande explores the example of Kannada-Modi that emerged in what is now northern Karnataka, and Modi’s presence in the remarkable multilingual milieu of Tanjavur.

In graphic terms, Modi was thus effectively positioned between Perso-Arabic and Devanagari. For all Modi’s worldly associations, therefore, what Deshpande identifies as the realm of “Modigraphia” actually emerged as an important alternative to what Nile Green has called “Persographia”, the Perso-Arabic script and powerful bureaucratic culture with which it was associated. “Modigraphia” gained particular ideological attractions from the later seventeenth century, as Shivaji’s court launched its drive to identify Marathi alternatives to the many Persian words commonly used within its vocabulary. During the 18th century, the business and political transactions of the Maratha empire carried Modi script right across India. Its bearers were the great legions of specialist scribes who serviced the empire’s formidable machinery for recording property rights and revenue collection.

Deshpande’s choice of Modi script turns out to offer key advantages in the current lively debates about India’s remarkable multilingual, multiscript history. Aside from notable examples such as Bhavani Raman and Sumit Guha, relatively few historians in this field have explored the actual business of writing and the experience of what Deshpande calls the “writerly self”. But it is Modi that brings writing into such close focus. Her study opens up a range of important new insights, not only into the labour of writing, but into its key spiritual and ethical associations. Through their adoption of Modi, western India’s largely Brahman clerkly classes were able to reconcile themselves to the service of the Deccan’s Muslim states and their use of Persian-inflected bureaucratic Marathi. Modi encouraged the sense that these impure occupations could be contained within the workaday world of the daftar or record office, leaving the purity of Sanskrit and the pieties of Balbodh devotional texts safe in the privileged spiritual space of the monastery or math.

Writing, a virtuous activity

Brahman clerkly work within the record office certainly entailed strenuous physical disciplines. Writing legible Modi with the speed expected of an efficient scribe required accuracy of pen and correctness in the shaping of cursive letter forms and conjuncts. Widely circulated mestak manuals taught many other clerkly competences: preparation of different coloured inks, correct folding of paper for presentation of tabular information, methods of authenticating documents with the right signs and seals, andmaintaining the order of paper records within an archive. Only with these skills mastered could a clerk begin to navigate the intricate world of agrarian assessment and revenue collection. This very tangible sense of Brahman scribal labour makes Deshpande’s account wonderfully fresh and vivid.

Yet if their use of Modi script enabled Maratha Brahmans to believe that they could live in two worlds at once, the reality was more nuanced and interesting. Based in his math at Chafal near Satara, the influential saint Ramdas circulated a new model of virtuous life to which moderate Maratha Brahmans might aspire. The saint constructed his model precisely out of the interplay between Modi and Balbodh, record office and math. Writing, he explained, was itself a virtuous activity, to be practised as part of a devout Brahman’s daily regimen. The labour of careful writing, learning of different scripts and writing of books were at once a form of bodily discipline and of devotional labour. Many worldly skills were actually quite compatible with Brahman purity. Mahant heads of maths themselves supervised property, managed revenues and had business dealings with state authorities.

With these compromises, it was not surprising that Ramdas’s sect and his oral discourses, transcribed and circulated by his devoted disciples, should have attracted Brahman adherents from across the Marathi-speaking world. As Deshpande explains in this strikingly original and important part of her book, the saint’s formulation harnessed the increasingly prestigious art of writing to Brahman literate authority, while maintaining the superior status of the guru’s own spoken word. Focusing on the rich archives that Ramdasi maths generated, she also shows how they participated in the circulation and performance of many genres of Marathi devotional poetry. The multilingual and multiscript environment of the maths saw Kannada, Telugu and Tamil verse copied in Modi or Balbodh, along with the heavily Sanskritised “pandit poetry” of the 18th century.

These Ramdasi materials, Deshpande argues, reveal the making of a new Marathi literary public that was at once local, transregional and multilingual in nature, and whose circulation of text and performance connected scribal, literary and religious spheres. In these settings, the boundaries between languages were always porous, as scripts and documentary forms seemed invariably to leak through them. The crossings were not random, nor endlessly fluid; rather, scribes made their choices of language, script, transcription or translation in the light of particular circumstances. Yet there is a further implication in these arguments about Modi’s role in securing, rather than undermining, Brahman religious identity, and the new literary public that emerged out of the connected worlds of daftar and math. On the eve of colonialism, the normative figure of the Maratha scribal servant was remade in an essentially Brahman image, a development fraught with consequences for the future of caste hierarchies in the region.

During the 19th century, Modi acquired very different associations. Colonial officials came to regard it as a barely legible script, and by mid-century, were moving to create their own new systems of top-down control. Uniform questionnaires worked to reduce assessment to a single number. Increasingly pressed to use Balbodh, Brahman clerks were still dominant in state administration, but remade now as a public service class, responsible for “public records” and “public revenues”. In government schools and colleges, Devanagari emerged as the preferred script for the well-educated, with Modi literacy deemed more suitable for the low educational expectations of rural pupils. With its abbreviated letter forms, Modi script was likewise a matter of dissatisfaction for Anglophone educationists and social reformers. Consumed with the all-important task of developing Marathi print, they also looked to Balbodh rather than Modi.

Deshpande shows how polarising forces of community as well as of class clustered around these questions. For conservative nationalist historians, Modi was no deficient relic. Rather, the great corpus of Modi archives contained the real history of Maratha achievement in building an India-wide empire. Scholars exploring the place of Marathi within the great Indo-Aryan family of languages were often most interested in its relationship with Sanskrit, rather than its precursors in the broad categories of Prakrit and first millennium “Maharashtri”. As languages themselves became objects of study, the old porous boundaries between bureaucratic Marathi and Persian attracted the disapproval of conservative nationalists such as VK Rajwade. His drive to “cleanse” Marathi of Perso-Arabic words, and to demonstrate that so purged, Marathi possessed a timeless completeness akin to that claimed for Sanskrit, is well known.

The arc of Marathi

What Deshpande shows so brilliantly, however, is that Rajwade’s distaste was no mere objection to linguistic mixing. Rather, it was powerfully shaped by the most conservative norms of caste and gender. In Rajwade’s etymological scheme, Marathi words with clear Sanskrit origins were “anuloma” or hypergamous, on the model of a bride’s approved marriage to a man of equal or superior caste status. Words whose origin could not be ascertained were “pratiloma” and therefore suspect, just as marriage with a groom whose origins were unknown was suspect, and likely to result in debasement of caste for both families. It was in this context of conservative Hindu nationalism, of course, that the figure of Ramdas acquired his familiar modern associations, identified with a muscular Hinduism directed at ridding the Maratha country of Muslim “aggressors”.

As is well known, the non-Brahman and Dalit opponents of conservatives like Rajwade were every bit as creative in their deployment of etymology, with their own uncovering of the “real” history of ancient Brahman invasion and oppression across the subcontinent. These strands of critique were to prove a powerful force in the interwar years and beyond, as political leadership in western India passed to an alliance of Maratha and other non-Brahman communities within the Indian National Congress. Hauntingly, though, as Deshpande describes, middle-class and Brahman-led literary associations oversaw the decades-long discussions of Marathi’s development as a basic tool of literacy for every citizen. Maharashtra’s potential future as a linguistic state added urgency to these discussions. They came to focus on a new discursive figure – that of the “common man”, whose effective participation in the public sphere depended on the development of a uniform orthography. Yet, perhaps unsurprisingly given the literary associations’ narrow social base, their questions were often technical in nature. How should Sanskrit words in Marathi be spelled? Should the terminal vowels of Marathi nouns be long or short?

Yet there were other influential strands of thought and action about Marathi’s potential as a vehicle for progressive social transformation. Their scholars sought, as Deshpande puts it, to escape the “bear hug” of Sanskrit, and to find an entirely different frame for the history of Marathi language and community formation. Some found it in a more radically egalitarian reading of Marathi devotional poetry, and the anti-caste Mahanubhav sect that flourished in the eastern province of Vidharbha. Others turned to Maharashtra’s pastoralist communities and traditions of folk religion to find the “deep history” of Marathi language and culture, and others again to further linguistic research to try to pin down an authentic popular tradition of radical abrahmanical thought.

This compelling drive to find an authentic core for Marathi language and culture continues to shape the field of modern Marathi scholarship, as it does for other regional vernaculars. Yet the underlying questions, thrown up from the early colonial period and after, remain the same. What boundaries and characteristics mark off one language from another? Who speaks and writes correctly? How can any language be made to represent the whole community of its speakers? With these questions, Deshpande reminds us of just how distant these modern concerns are from the earlier history she has traced for us, when Modi helped to protect Brahman identity, and scribal power depended on deft navigation between different languages, scripts and documentary forms.

It is, therefore, a very long arc of development that Deshpande explores in this extraordinarily rich study. Through the lens of Modi, she reminds us of the inescapable materiality of scribal labour, and the anxieties which surround its periods of major transformation. She identifies the forces – local, regional, subcontinental – that determined the choice of script and language in early modern India. She follows, through this long arc, the periodic reshaping of older boundaries and relationships which enabled different Brahman elites to protect their authority. She explores the colonial remaking of these complex relationships, and the questions about accessibility and representation which now pervade all discussions of language policy.

But what of Deshpande’s “writerly self”, and its relationship with what sometimes seems the remorseless march of the fixed, the written, over the spoken word? At the heart of the book, and one of its most arresting insights, is an understanding of written language as itself a capacious and almost infinitely adaptable medium for human expression, whose fixity often turns out to be an illusion. For all of written language’s unavoidable entanglements with power, its protean qualities will always open up spaces of agency and choice for writerly selves, even if – as in our own present times – quite different dexterities of fingers now generate writing, and its production depends on hands remote from our own.

Rosalind O’Hanlon is Professor Emeritus of Indian History and Culture at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of the British Academy. Her latest book is Lineages of Brahman Power: Caste, Family, and the State in Western India 1600–1900. Her previous books include Religious Cultures in Early Modern India: New Perspectives, coedited with David Washbrook, and At the Edges of Empire: Essays in the Social and Intellectual History of India.

Scripts of Power: Writing, Language Practices, and Cultural History in Western India, Prachi Deshpande, Permanent Black and Ashoka University.