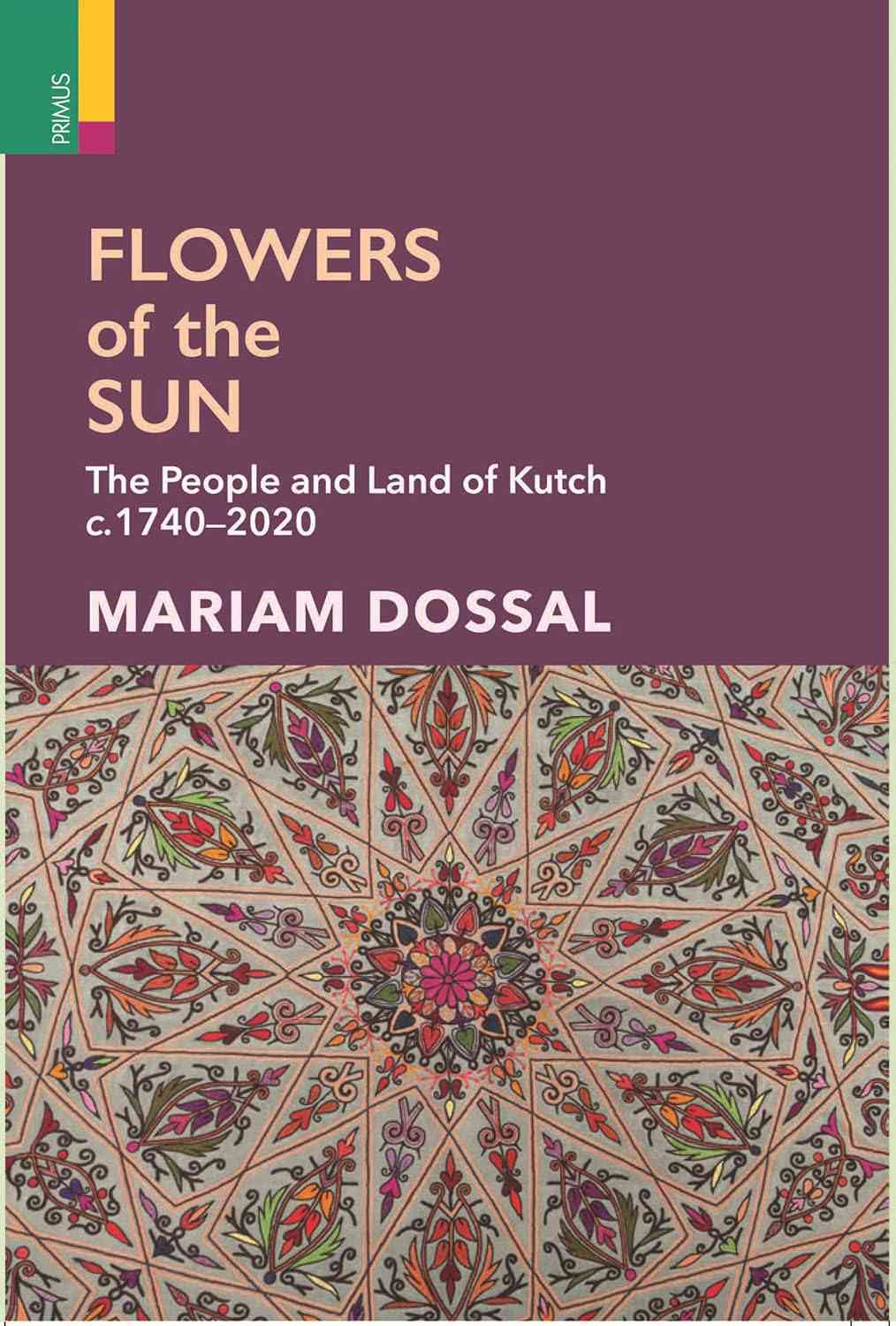

Mariam Dossal’s new book, Flowers of the Sun: The People and Land of Kutch c.1740–2020, is an ambitious project. It is not only a history, nor is it an attempt to account for a people. It is instead a gathering up, an assemblage and from the ways in which material is placed, a composite emerges that allows the reader to fill up some gaps in knowledge. For a former Professor of the Department of History, University of Mumbai, this is a passion project which takes in archives, sure, but also uses interviews and personal accounts to build a picture of an ignored area.

I have to confess that I have very little knowledge of Kutch, and so perhaps I am the perfect reviewer or the worst kind. I have been to the Rann, where I learnt to my horror that the area did not rhyme with paan. My memory of it is heat and salt and a shopping trip in which my host smiled at me and said that the shopkeeper must have liked me.

“Why would you say that?” I asked.

“He offered you water. Most people get Thums Up.”

Dammed and damned

It is a dry land and the aridity, as Dossal explains, can be accounted for in three ways. The first is human intervention, where rivers are dammed and diverted and water stops flowing. (This may sound familiar but that is what we can do to each other, thus damning from on high those who are at the bottom of the pyramid and suffer the most.) The second is geographic, and the third is governmental indifference. Dossal shows how each successive Five-Year Plan simply cut down on what the earlier one had promised and when the Narmada was dammed (or damned), she quotes Lyla Mehta’s study which says, “Instead of allowing for the irrigation of 9.45 lakh acres of land in Kutch, only 95,000 acres of land were to get irrigation. In this way, less than 2 per cent of Kutch’s area stands to benefit from the Kutch Branch Canal.”

It seems as if governments did not think much of Kutch, not even when there was a terrible earthquake there on January 26, 2001, a 7.7 on the Richter scale. (Remember that each number up means a tenfold increase in wave amplitude; the energy released increases by approximately 32 times for each whole number increase, not 10 times.) When Chief Minister Keshubhai Patel of the BJP appeared on television, reporters asked about relief measures and Pravinchandra Shah remembers that he responded: “Again and again you are asking me about Kutch. Should I be concerned about Kutch or about the situation here at Ahmedabad/Gandhinagar?”

(Before you ask, “Pravinchandra Shah, who?” he is one of the unlikely heroes of the story and we would really have liked to know more about him. He was introduced to Dossal and she interviewed him, only to discover that he had been a journalist and had masses of material on the area, going back decades, which he and his wife Irene had preserved intact. Much of the material in the book, Dossal says, came from Pravinchandra Shah’s squirrelling away of material that pertained to the area. When I read about this man from Takka Panvel, I was put in mind of Adil Jussawalla’s archives, the papers he put his faith in, the cuttings he made, not of his own work, but of other writers’ work too. It is a wonderful collection and it is to be hoped that it is being preserved well in the library to which it has been consigned. Take a look at the picture of the Kutch Samachar of April 2, 1894, with the magnificent headline “Kutch, An El Dorado of Incapables.”)

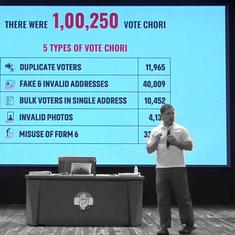

You do not have to look far for the reasons behind such political indifference. Kutch is underpopulated and the fewer the votes, the less the interest. Kutch was often subsumed into Kathiawar, so that when Gandhiji visited, his Kathiawari hosts did not invite anyone from Kutch. The Mahatma was not impressed, for he saw the casteism of the area at close hand. He never came back.

Political life of Kutch

Dossal has origins in Kutch but she is even-handed. She points to this casteism and also talks about the role that it had in the horrors of the slave trade. Kutch was once a thriving centre of maritime trade, sending dates and sugar-candy and cloth to far-flung lands. (We think little of this but the “Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir”, the first line of John Masefield’s poem “Cargoes”, actually refers to Nalla Sopara.) Bhadreshwar, one of the earliest of these port towns, has a history that Mehrdad Shokkoohy has traced back to the pre-Christian era. Those were glorious times with dates and cloth and later fish going up and down the coast.

The sailors kept logs which were known as Roznamas, a term that sounds so beautiful that I am tempted to rechristen all my diaries into Roznamas. This is the lure of the sea, where the nakhuda steers by the stars, and is aided by the Dariyari or sea calendar and dhinghies ply the coast. I should have liked to know what samudra phin is but there was no explanation. One could have hoped for better editing from Primus, for this is really something an editor points out to the author who may be too close to the work to know what might need explication.

As I read about the roznamas which turn up on Page 194, I longed to see one. And then my wish was granted a hundred-odd pages later, meticulous lines of numbers that meant the difference between a good day to sail and a bad day to sail. If you are of the kind who thinks that there is much to be said in old wisdom, perhaps you do not want to set out for a sea voyage from anywhere on the coast of Kutch on any day other than Monday or Thursday when “the sea and wind remain calm and pleasant”. (Sunday: thunderstorms; Tuesday: heavy rain; Wednesday: big waves called zugars; Friday: no stars, thunderstorms, zugars; Saturday: profound but silent waves.)

A word about the photographs. Their quality points to the nature of the enterprise; this is a passion project and so most of the photographs have been taken by the author or by others. No professional seems to have been involved. This means that one does not get as much as one would like out of the visual material. On page 393, we have two pictures and the captions read: “a Roghan artist painting on cloth, Nirona, central Kutch” on one and “Bell-metal work, Nirona, central Kutch”. The photographs are both credited to Ranjitsinh Jadeja. The Roghan artist is hard at work so we do not see his face. Nor do we see the work. The bell-metal worker is holding up too bells but we cannot see them either. Neither man is named which follows the unfortunate tradition of not naming the folk artisan.

At a time when the highest in the land can turn their guns on words like secularism and call them wounds on the body politic, it is good to read about the syncretism of the Kutch area. “The Solahkhambi Masjid and the Dargah of Ibrahim Pir, also known as Pir La’l Shahbaz, which date back from the twelfth century, are of great architectural significance. Shokoohy states that they are the first Islamic structures to be built in the Indian subcontinent.” They were given permission to build by the Jain council.

Perhaps this comes from the balancing act that was political life in the area, with the Maharao or ruler always having to deal with the Bhayad or Royal Brotherhood of which he was the titular head but whose power held his in check. Where power is shared, it is an easy lesson to learn: you take everyone with you or you end up alone. And no one survives deserts alone. The entry of the British did much to upset the balance but even there we find some extraordinary figures that Dossal’s scholarship has excavated for us: Lieutenant James McMurdo, for instance, once visited Kutch in the guise of a sadhu. “Based in Bhuj’s main bazaar he gained a following and was venerated as Bhuria Baba. This ploy served him well and he was able to obtain valuable information about political developments in the capital which was then passed on to his superiors in Baroda and Bombay.”

What are our scriptwriters doing? Not a single film on Baba McMurdo? Perhaps Dossal’s book will find its way into the hands of some enterprising young filmmaker of Kutchi origin in Britain or Los Angeles. Stranger things have happened on the crossroads of culture.

Jerry Pinto is a poet, novelist, short story writer, translator, and journalist. His latest novel, The Education of Yuri, was published in 2022 by Speaking Tiger Books.

Flowers of the Sun: The People and Land of Kutch, c. 1740–2020, Mariam Dossal, Primus Books.