The tall iron gates open to a small yard. On the left lies a reception room with a desk and few chairs.

As you walk in, there is a locked door on your right.

If you go past, you enter another small and dark room, which has steps that lead to a neon-lit, windowless hall.

Forty young men sat solemnly on the floor of the hall eating eggs and bread for breakfast one morning last week. Most had shaven heads.

Piled up against the wall were iron beds with mattresses covered in white sheets. On the other side of the room, in wooden cupboards, their clothes were stacked on half-a-shelf each.

Wall posters spelt out the daily schedule, packed with hour-to-hour activity, with sessions titled “encounter”, “family deal”, “mood making”.

Neither a hostel, nor a prison, but somewhere in-between, the Jeevan Jyot Nasha Chadua Kender, located near the town of Khanna, is one of the 80 licensed drug de-addiction centres in Punjab.

If its owner is to be believed, in the coming days, the cramped halls of centres like this will fill up further as panicked parents send young boys to rehab keep them away from harm during the elections.

“Parents get their boys admitted before elections,” said Avtar Singh Aujla, the centre’s owner, “because young men are in demand during elections.”

He explained, “Parties need them to roam around, do party work, gather crowds. Youth ko kahenge 200 bande le kar aa wahan nasha free karaa denge. They are told, 'Get 200 people, we will supply drugs for free.' Some of them overdose on free smack and die."

This may sound like an exaggeration but in the first 40 days after the model code of conduct came into force, the Election Commission seized drugs worth Rs 700 crore in Punjab: 136 kg of heroin, 14,823 kg of poppy husk, 76.2 kg of opium and 51,623 kg of molasses.

***

“Back in the day, patients were middle-aged men,” says Dr Aniruddh Kala, the founding president of the Indian Association of Private Psychiatry, who started the first acute psychiatric care clinic in Ludhiana, which also provides treatment to drug-addicts.

With its proximity to the poppy fields of Afghanistan, Punjab has had a long history of opium consumption. The consumption of small quantities of the intoxicant was socially and culturally acceptable – much like alcohol. Farmers took spoonfuls before starting work in the fields. The experience of Partition and the unrest in the eighties led many to look for escape.

But most opium consumers remained in control of their indulgence. The only ones who came for de-addiction were those travelling abroad, says Dr Kala. “One of my first patients was an old man leaving for Canada to visit his son,” Kala said. “He said he wanted to quit because wahan to milni nahi hai.”

In the early nineties, however, bhukkhi (poppy husk) made way for chitta (white heroin powder). The synthetic derivatives of opium – morphine, heroin, smack – came mostly from Delhi. “I called it the Shatabdi syndrome,” said Dr Kala. The Shatabdi Express is a fast train running from Delhi to Ludhiana. “It started in 1994,” he said. “At that time, if your village was not on the route of the train from Delhi, you were relatively safe.”

But it did not take long before the synthetic drugs spread more widely, and also proliferated in forms. Cough syrups, psychotropic medicines, pain-killers meant to be prescribed by doctors were available over the counter.

Today, Dr Kala says the average patient is a young man who is “disruptive, troublesome, stubborn”.

“Sometimes parents bring a young man to my clinic and he gets angry at them. He says, ‘You said you were going to get me a motorcycle and you’ve brought me here.’”

Analysing the social factors driving drug abuse in Punjab, Rahul Advani of the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, writes in a research paper, “The practice of extreme drug abuse emerges out of tension created by the combination of a relatively wealthy and aspiring rural population with a slowing agricultural economy.”

After the years of the Green Revolution and rising incomes, Punjab’s cash crop economy has run into declining yields. The government’s response has been to increase subsidies for farmers, which has pushed the state’s finances in the red, leading to declining investments in education, health and industry.

While their earnings have declined, the levels of aspiration among people have not. Nor has the culture of hyper-masculinity.

With an aversion to toiling in the fields and a lack of industrial jobs, Punjab’s youth have both time and cash at their disposal. Coupled with the easy availability of drugs, this is creating “the frightening possibility of an entire generation in Punjab being lost to drugs”, Advani writes.

“From the inability to encourage crop diversification, the hollowing out of education, the failure to create jobs and industry,” said Dr Kala, “what we are seeing as the drug problem is nothing but a failure of governance.”

***

The more insidious connection between drugs and Punjab’s political system came to light in January when a police officer-turned-druglord named Jagdish Singh Bhola was arrested in a synthetic drugs haul case. Bhola alleged that Akali Dal leader Bikram Singh Majithia was the kingpin of the business. Majithia is the state’s revenue minister and the brother-in-law of deputy chief minister Sukhbir Badal.

The police have arrested 55 people in the case, including Akali Dal politicians Jagjit Singh Chahal and Maninder Singh Aulakh. The Hindu reported that their interrogation revealed that “they had frequently used government vehicles to smuggle drugs…Chahal has three pharmaceutical units in Himachal Pradesh, from where precursor chemicals were being diverted to make party drugs Ice and Ecstasy.”

Bhola threatened to reveal more names of politicians if the case was handed over to the Central Bureau of Investigation. At the moment, the High Court of Punjab and Haryana, which is hearing a petition in the case, has held back from a CBI enquiry.

But coming in the run-up to elections, Bhola’s revelations, The Hindu writes, have “thrown Punjab’s acrimonious polity into a tizzy”.

At a recent election meeting, Arvind Kejriwal went for the jugular, as reported by The Hindustan Times.

“Who are the traders of drugs?” he asked the crowds at a rally in Sangrur.

“Majithia,” the crowd replied.

“Who is Majithia?”

“Brother-in-law of Sukhbir Badal.”

“You know the truth, still you voted them in the last elections…”

Not just Arvind Kejriwal, Congress leaders Ambika Soni and Amarinder Singh have also been attacking the Akali government and giving great prominence to the drug problem in their speeches. Even Arun Jaitley, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s candidate from Amritsar, could not get away from the subject, despite his party’s alliance with Akali Dal.

For their part, the Akali leaders have tried to shift the blame to the centre, claiming it has failed to curb the flow of drugs from Pakistan into Punjab.

Meanwhile, one of their candidates, the Lok Sabha MP from Faridkot, Paramjit Kaur Gulshan, caused some embarrassment to the party when she reportedly told voters she supported the opening of licensed poppy husk shops in the state.

***

Away from the election sound and fury, thousands of men, both young and middle-aged, spend days and nights in grim, airless buildings that pass off as de-addiction centres.

Unregulated until recently, the centres have been extremely controversial.

They sprung up in response to the need of families unable to tackle difficult men hooked to drugs.

But the absence of consent created a lot of room for abuse. For instance, it became possible for people to get relatives with whom they had legal disputes picked up and sent to such centres.

A petition in the High Court claimed that the owners of the centres were picking up men from their homes in the dead of the night, confining them against their will, beating and torturing them, sometimes to death.

In response to the petition, the High Court asked the government to frame minimum standards, which it did.

Now, the centres require a licence and must have both professional psychiatrists and counsellors on board. An addict must be treated in a hospital and his consent must be taken before he is brought to a centre.

But those familiar with the workings of the centres said the rules have remained on paper. Men continue to be picked up from their homes in their sleep.

“The addicts who have had previous experience of the centres and are familiar with the strategy have now started keeping knives and guns under their pillow,” said the owner of one centre, on condition of anonymity.

While they take most addicts to hospital, the more violent ones are brought directly to the centre. “Since withdrawal without medicines is very painful, causing severe diarrhoea, nasal discharge and body ache, the men are not able to flee,” the man said.

***

The owner of Jeevan Jyot, Avtar Singh Aujla, a hefty man with ruddy cheeks, would do well as a bouncer outside a night club. He told me that he is an ex-addict and his experience comes handy in weaning away other men from drugs.

What was his success rate, I asked.

Of the ten people who came to the centre, eight did not stay to complete the nine month programme, he said. “That leaves only two,” he said, “of whom we are able to cure at least one.”

Gursharan Singh, 23, could be one of those. The son of an industrialist, he was a student at Chandigarh’s DAV college, where he says, “curiosity got the better of him” after he saw his seniors inject drugs.

“Initially, there was no problem,” Singh said. “I continued to get good marks.” But eventually, things came to such a pass, that on the day of his sister’s wedding, he ran away with her jewellery and sold it to buy drugs.

Today, after spending three months at Jeevan Jyot, he feels he is on the recovery path. His head is shaven, his body is clean.

Who does he hold responsible for what he has gone through, I asked him.

“Myself, who else,” he says.

But does he see any wider pattern in the easy availability of drugs in Punjab?

“The government is responsible to some extent,” he says, in what sounds like an afterthought.

Does he plan to vote in the coming election?

“I don’t want to vote,” he said. “All politicians care for themselves. Koi kissi ke liye nahi hai. Bas apni life happy honi chahiye. Parents ko khush rakhna chahiye. I just want to be happy and to keep my parents happy. That’s all."

***

He has a puma tattooed on his neck. His turban is stylish. So are his clothes. The son of a farmer in a village in the district of Fatehpur Sahib, 22-year-Sukhwir Singh picked up a heroin habit went he went to the city to attend college. As he started losing weight, his parents begged him to give up drugs. Fights took place at home. Nothing changed. But a month ago, his hands started to tremble and he began to fall unconscious. That’s when he asked his mother to bring him to Ludhiana, where he had heard about Dr Kala’s clinic.

After spending two weeks in acute care, Singh says he is now ready to go home.

“Who do you think is responsible for the drug problem in Punjab?” I asked him.

His mother, Ranjeet Kaur, replied, “Pakistan.”

“Pakistan is sending drugs across the border so that the youth in Punjab are finished,” she said. “Punjab de poore jawan bilkul khatam ho jaan. And when there is a war, no one is fit enough to fight. Jad kad ladai ho ek koi war karne joge na rahen.”

But what about the Punjab government, I asked.

“Sarkar to aap khandi hondi hai.”

“You mean people in the government take drugs?”

“No, she meant they are profiting from drugs,” Sukhwir Singh intervened. “You must have heard about Majithia, haven’t you?”

Who would they be voting for, I asked.

“Appa Sikh haan. Sikhaan nu paunde haan. We are Sikhs. We vote for Sikhs,” the mother said.

But the son had a different view. “Naya banda chunenge. Kejirwal ko vote payenge. We will go for a new leader. We will vote for Kejriwal.”

If the Aam Aadmi Party does well in Punjab – and there are chances it will – a large part of the credit would go to the way it has identified the drug problem as the central theme of its election campaign, coining a slogan which is getting much attention in rural Punjab: “'Na bhukkhi nu na daru nu, vote padaange jhaaru nu.' Vote for the broom, not for drugs and alcohol.”

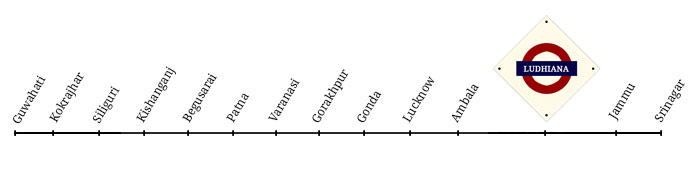

Click here to read all the stories Supriya Sharma has filed about her 2,500-km rail journey from Guwahati to Jammu to listen to India's conversations about the elections – and life.