The two-volume book is a collaboration between Indian and Chinese scholars. On its website, India’s ministry of external affairs explains that the volumes have the same content in both English and Mandarin. This perhaps explains the sanitised version of history, as writers from both countries attempt to tone down any criticism of the other.

There are the expected entries, such as ones on veteran travelogue writers Faxien and Xuanzang’s journeys to India. Almost a quarter of the book is devoted to interactions based on and around Buddhism.

But interspersing the official prose are little-known anecdotes of how cucumbers came to China and how dictionaries developed as interactions between the countries increased.

Here is a selection from the encyclopedia:

Tagore has a birthday party in Beijing

In 1924, while visiting Beijing, Rabindranath Tagore received a pair of precious stones inscribed with his name in Chinese: Zhu Zhendan. The encyclopedia says that Zhendan, meaning the sun that rose after a storm during the day, was what Indians used to call China. Tianzhu, on the other hand, was China’s name for India.

While giving him the stones, the philosopher and journalist professor Liang Qichao told Tagore that this was a perfect symbol of Sino-Indian unity.

Tagore celebrated his 63rd birthday in Beijing by attending one of his own plays performed in Chinese. His birthday in May coincided with a longer 49-day tour he was taking of six cities in China.

A rare colour photograph of Rabindranath Tagore in 1921

Photo credit: Albert Kahn

He had arrived in the country at a time of some turmoil. The Republic of China had deposed the last emperor from the Manchu dynasty in 1912, but by the 1920s was finding it difficult to retain power, as local military leaders began to fight back. But Tagore’s trip was free of disturbance. He gave six speeches across six cities and returned home duly impressed with both his name and the people he met.

Cucumbers cause a minor diplomatic incident in China

The encyclopedia says that the Indian kachumber was taken to China around the 2nd century BC by Zhang Qian, a subject of the Western Han dynasty. The locals called the plant “gourd from Hu”. Hu happened to be the Han word for people not from their region, but it was also the name of people in the western regions.

The fruit that annoyed an emperor

Photo credit: Muu-karhu

When the Zhao dynasty assumed power some years later, the emperor was a Hu. Shi Le, the new emperor, did not want his people to be associated with a foreign-looking gourd, which is why he renamed it huanggua. And in this simple manner peace was restored.

India teaches China kung fu

The 2011 Tamil film 7aum arivu (7th Sense) begins a thousand years ago when a Tamil prince, Bodhidharma, leaves his home and travels to China to prevent a deadly disease from spreading to India. He does so at great peril to himself and then knocks out a band of raiders single-handedly, as an afterthought. The villagers beg him to stay and teach them his secrets. With that is born Shaolin kung fu.

7aum arivu – later dubbed in to Hindi as Chennai vs China – crosses the boundaries of the ridiculous when it becomes a science fiction thriller in the present day. But at least parts of its Bodhidharma lore are accurate.

Shaolin kung fu, made in India

Photo credit: Kevin Poh

The Buddhist monk is actually acknowledged as the founder of the Shaolin school of kung fu and finds several mentions outside the entry dedicated to him in the India-China Encyclopedia. Instead of riding a horse across India and China, he is said to have sailed to Guangzhou by sea. Sadly, he did not miraculously cure an entire village.

Chinese scholars used a children’s book to learn Sanskrit

In the 10th and 11th centuries CE, as Chinese scholars once again showed interest in translating core Buddhist texts from Sanskrit, they only had to fall back on existing tools.

The Siddharastu, says the encyclopaedia, could be read by a six-year-old in six months. The Sanskrit book was also a useful primer for all Chinese scholars seeking to learn the language of Buddhist religious texts. Reports from that time said that chapter 12 was particularly useful to both Indians and Chinese as it also had an uplifting moral message.

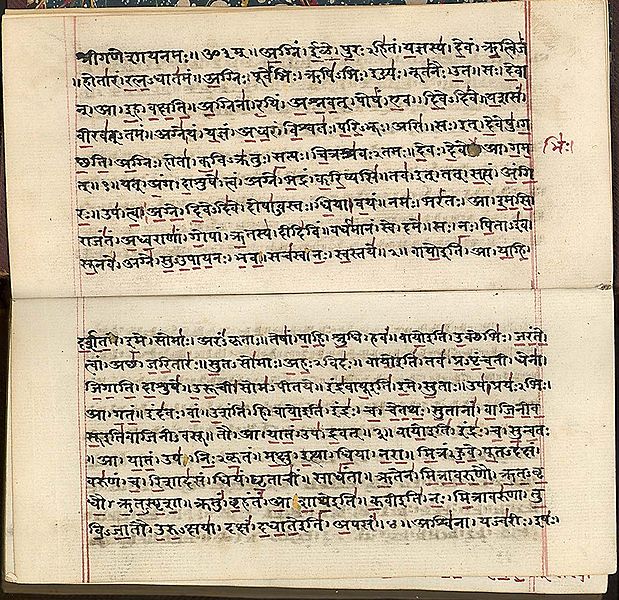

Rigveda manuscript in Devanagari, early 19th century

Photo credit: Nasjonalbiblioteket

There were other dictionaries as well. In the 9th century CE, Kride Zukzain, tsampo or ruler of Tibet, commissioned Indian and Tibetan scholars to put together a list of Sanskrit-to-Tibetan words to help them read Indian texts. That book was later included in the Tibetan canon.

Chinese doctors might have studied ophthalmology in India

Surgery, according to the encyclopaedia, was not well developed in China. The Chinese preferred holistic healing. While there is little recorded evidence of the exact procedure, several Chinese scholars mention cataract surgery with some interest, referring to it as the surgery of the golden needle that returns vision to people.

Acupuncture chart from the Ming Dynasty

Photo credit: The History of Medicine

There was little experimentation apart from this because Indian and Chinese medical practices were based on different founding philosophies. Among the few who experimented in combining Indian and Chinese medical practices was Yu Fakai, a monk of the Jivaka school of philosophy, who was skilled at acupuncture. Tao Hongjing, a medical scholar, praised Indian medical theories in his works as well.