"What if Ebola breaks out in a slum? We wouldn’t know what to do. Of course," he consoled himself quickly, "Nobody in a slum would ever come within a mile of the airport. So the chance of getting infected is practically zero, right?"

Wrong. How utterly wrong.

If Ebola breaks out in a slum, we must know what to do because we’ve been there before. And his second observation is exactly what made things go so horribly wrong that time.

We’ve had Ebola before?

No, but we’ve had the plague. It broke out in September 1896, but let’s ignore the date. That moment was incendiary, like it is now.

Mumbai didn’t have slums in 1896.

Hell, yes we did.

It was Bombay then and we’ve had slums since the 17th century.

Surely those were chawls, not slums?

The distinction is invidious.

In 1896, in newly industrial Parel, people lived 64 to the room. About ten of them were employed. The rest were friends and relations escaping the famine.

That was only the plague. This is Ebola!

Onlythe plague?

By January 1900, more than 2.9 million had died of the plague in Bombay Province. The recorded number of cases in this period was 3.8 million. The mortality was even higher in the first decade of the new century. Bombay had epidemics every year until 1923.

Fever. Collapse. Death.

The pattern is the same as Ebola.

Plague victims died exactly as Ebola victims do, within a day of onset, bleeding from every orifice.

Plague’s an ancient disease. The treatment may be recent, but surely doctors knew what to expect!

Before 1896 nobody in the city had seen a case of plague. Scientists knew just as much about the plague germ as we do of the Ebola virus today ‒ which is to say, practically nothing.

It had a name and identifiable markers, anything more was guesswork. Doctors didn’t know what it would do, how it would move, what damage it would inflict. They could only watch and learn. As are courageous doctors and nurses in Liberia are doing now, learning on the job.

But science is so much more advanced now. They couldn’t have known much about immunity in 1896. And wasn’t there a vaccine against plague?

Agreed. They didn’t know much about immunity, and yes, there were vaccines and therapies and none of them worked.

Are we so much more advanced today?

We don’t know how Ebola emerged ‒ which really is the key to containing an epidemic. We don’t know how the body defends itself against its assault. Tentative vaccines, we’re told, are being tried. But can your family doctor, or even your friendly neighborhood five-star hospital, produce one to protect you? Not a chance. There are no drugs to cure Ebola.

Yes, we can dress better for Ebola than they did for the plague. We can do spacewalks in those spiffy protective suits.

Incidentally, the European plague doctor, circa 1400 had an even hotter wardrobe. But by 1896 it was considered too retro, and Bombay’s doctors did little to protect themselves against the plague.

Thank God for quarantine! It’s all up to airport surveillance now.

Here we go again.

Quarantine didn’t work with the Black Death of medieval Europe, it didn’t work in Bombay in 1896. Quarantine was in full force when plague spread from one continent to another. Then, as it is now, quarantine was the first response. Unfortunately then, as now, it remains the only response ‒ a knee-jerk response, the startled reaction to panic. It’s also the most violent, the most primitive human response to danger. It is xenophobia based on the perception that the outsider is evil and must be kept out at any cost. Shoot on sight orders have historically been part of quarantine.

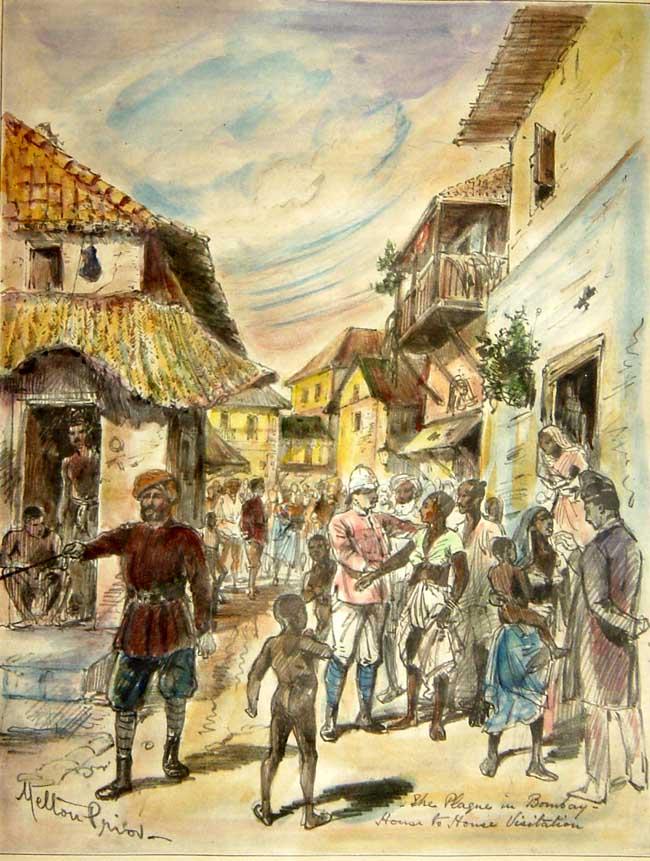

Isolation, segregation, quarantine were all forms of exclusion practiced in Bombay in 1896. Houses were inspected, suspicious cases were dragged out to hospital where they invariably died, their goods and belongings were burnt at street corners, relatives were herded into plague camps while their houses were de-roofed, sluiced with perchloride of mercury, fumigated and limewashed. Survivors were given new clothes and sent back to their sanitised homes ‒ only to contract the plague again the following week.

Bombay’s plague camps and temporary plague hospitals had deeper political implications. They allowed the Sarkar to control the population by fragmenting it on the basis of religion, caste, and community.

That was the British Sarkar. This is independent India!

Right. Has the country ever been more divided, more polarised, than it is now? We’re a nation on the brink of fragmentation. Xenophobia’s practically a birthright for us Indians. What better tool for fascists than the threat of an epidemic?

The plague camps of Bombay were the blueprint for the concentration camps of Nazi Germany. How long before we travel that road today?

So if isolation didn’t work in 1896, what did? Is there anything in that experience which might help us today?

The only thing that worked in 1896 is what’s working today in Liberia.

We can’t read that in the historical narrative of the 1896 plague, but we can in the notes of the doctors, and they did keep detailed notes.

One man in particular, Dr NH Choksy of Arthur Road (now Kasturba) Hospital recorded his personal experience of over 4,000 cases of plague through eight epidemics. He relied solely on what he observed. He had no cure, so he anticipated complications and made ready to face them.

This is what doctors (often with a sneer) call "supportive treatment". It means taking every step to prevent the body’s major organs from failing ‒ and it’s the only thing doctors in Liberia are now doing. Because, the assault of Ebola is the same as the assault of plague, the same as the assault of any and every infection that overcomes the body’s barriers. This assault is on the organs that keep life going.

Doctors in Liberia are battling to keep their patients hydrated, just as Dr Choksy did, to prevent circulatory failure, to prevent the fatal effects of shock on heart, liver, kidney, brain.

The worst we can do is to subscribe to the viewpoint of that guy on the plane ‒ that people exist in airtight compartments, that the ragged man on the roadside can’t possibly rub shoulders with deodorised airport staff. This presumption is naïve in a citizen, but criminal in scientists or policy makers.

And yet, here we go again.

Ishrat Syed and Kalpana Swaminathan are surgeons who write together as Kalpish Ratna. Their new book, ROOM 000: Narratives of the Bombay Plague will be published in January.