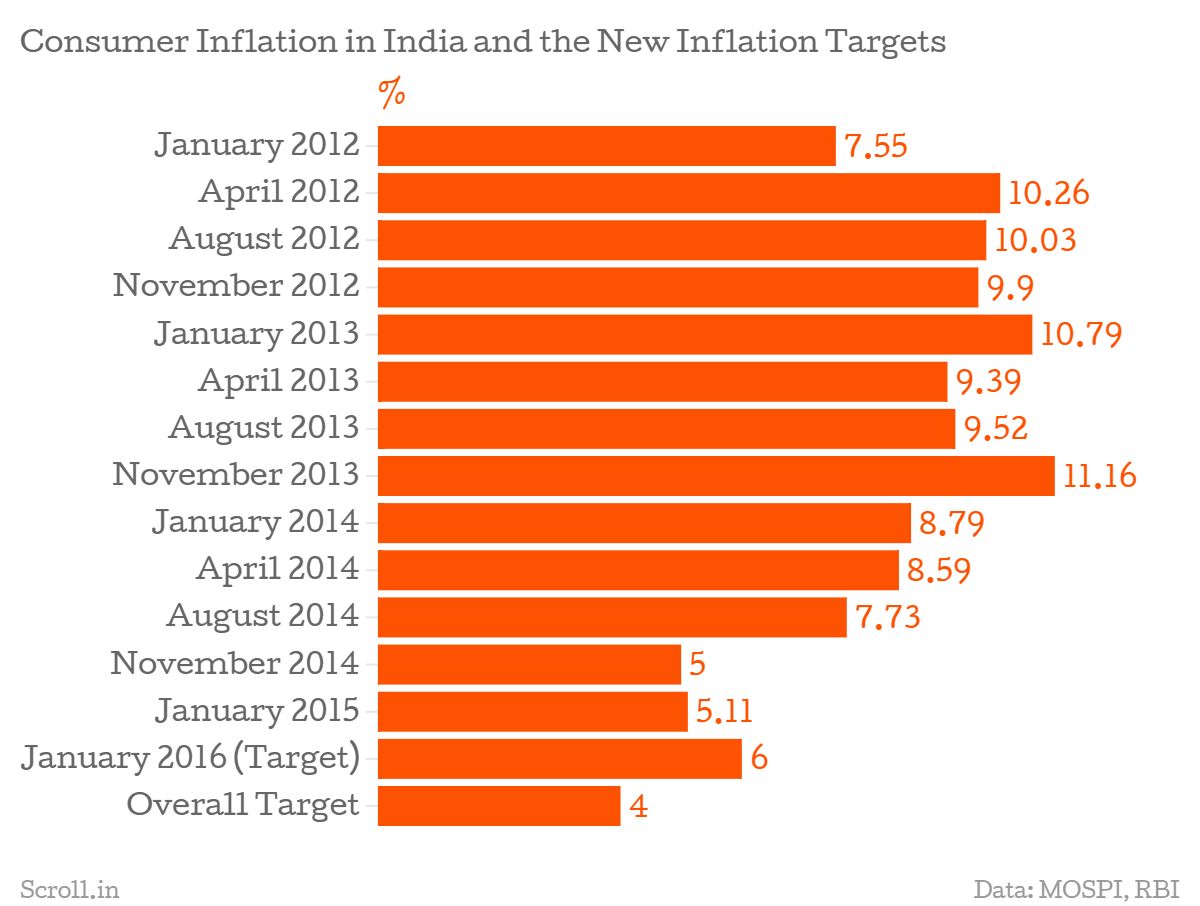

That represents a rather substantial shift for India's central bank, which for a few decades now has taken a more all-encompassing view of monetary policy. In a note released on Monday, the finance ministry announced that the main task of the RBI would now be to target 4% consumer inflation, with a leeway of two percentage points on either side to account for fluctuations. For starters, the RBI will aim to hit an inflation rate of 6% by January 2016. The rate currently stands at 5.11% but it has been incredibly volatile in the last few years.

The agreement comes with a few other riders. For one, the central bank will be expected to publish a document every six months explaining what the sources of inflation are and forecasting the inflation rate over the coming months. More pertinently, the RBI will have "failed" if the inflation target falls outside the 2%-6% zone for more than three consecutive quarters, following which it will have to publish a report explaining why this happened and how it intends to fix things.

Policing prices

The document, which was signed on February 20 but only announced on March 2, makes no mention of a monetary policy committee that would, over a longer term, alter that inflation target as and when necessary. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley had spoken about such a committee in his Budget Speech.

"To ensure that our victory over inflation is institutionalized and hence continues, we have concluded a Monetary Policy Framework Agreement with the RBI, as I had promised in my Budget Speech for 2014-15," Jaitley said. "This Framework clearly states the objective of keeping inflation below 6%. We will move to amend the RBI Act this year, to provide for a Monetary Policy Committee."

That means that, while the agreement with the RBI leaves monetary policy entirely to the central bank for now, whenever the act is amended, it will no longer be the only one holding the levers. Another announcement from the Budget speech, that of a debt management agency which will put together India's external and domestic borrowings, will further take away the RBI's powers.

What Rajan wants

This isn't a power grab from the government, however. It's something Raghuram Rajan has himself argued for over the years. In a paper written back in 2008, after submitting a report of the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms which he chaired, Rajan argued that India's central bank has too much on its hands with attempting to keep inflation down and also have a handle on the exchange rate – parameters that don't always move together.

"By trying to do too many things at once, the RBI risks doing none of them well," Rajan wrote, along with Eswar Prasad, in the piece titled, 'Why an inflation objective.' "If the public never knows whether the central bank is going to focus on the nominal exchange rate or the inflation rate, it is confused. It is likely to have higher inflationary expectations, and be more sensitive to any local price jump."

Instead, the central banker argued for the RBI to have one simple objective, low inflation, and to clearly communicate its target to the public. "Focusing on an inflation objective can be useful in communicating that monetary policy has its limits. It can be a recipe for disaster if the public believes that monetary policy is a panacea for all the ills that an economy faces, and expects the RBI to produce magic somehow," the paper said.

Glide Path

Rajan, in fact, initiated this move towards inflation targeting in January 2014, announcing a general target for the central bank, referring to a "glide path" laid out in an earlier report that attempted to create a blueprint towards reducing India's stubborn inflation. He was then spurred on to move this after a face-off of sorts with the incoming Modi government in May, when Bharatiya Janata Party leaders sought to push the central bank to cut interest rates and spur growth even when inflation was still high.

Rajan has said before that Parliament should set the inflation target, a task it could do by setting up a monetary policy committee, which the RBI will then have to achieve. "What inflation target to have should be something set by the elected representatives of the people and not something the central bank decides on its own," Rajan said in February.

This de-politicises the task of changing interest rates, with the central bank not expected to react to sudden shocks in the system and gives investors a clear idea of what the RBI's overall aim is, adding stability to the system in terms of forecasting. By formally doing this, even though it means giving up some of the central bank's independence, both Rajan and the government are making a move that could make Indian economic policy a less volatile beast.