He was only 23.

In November, Avinash and his mother Kaushalya left their home in Georai block in Maharashtra’s Beed district to begin a season of work at a sugarcane processing factory in Dharwad in Karnataka. It was the first time they were going to cut cane.

As one of very few landowning Dalit families in the region, they had until then managed to escape the seasonal cycle of migration that most Dalits undertake. But in 2014, repeated losses on the family farm depleted their resources, as did an overdue loan Avinash had taken to build a permanent house in place of their hut. They had no choice but to join the ranks of migrant workers.

Avinash found the experience humiliating.

“Just before he left for Karnataka, he told us how neighbours had been making comments about how he could not even build a house for his family,” said Sanjay Mal, a friend and former neighbour of the family.

Five days after they left for Dharwad, his father, Nana, who had planned to join them in a week, got a call. Avinash had been found hanging from a tree outside the factory. Authorities there concluded that he had committed suicide.

A new suicide hotspot

Avinash is only one of many young people who killed themselves in 2014 due to the agrarian crisis in the Marathwada region in central Maharashtra.

Until recently, the eastern region of Vidarbha used to report the highest number of farmer suicides in the state. But last year, Marathwada gained the dubious distinction of overtaking it. This is not to say that Vidarbha has improved at all. The number of farmers who kill themselves there daily continues to be distressingly high. But the spike in deaths in Marathwada is new and alarming.

Nearly three times as many farmers killed themselves in the region in 2014 compared to the previous year.

What is causing such acute farm distress in Marathwada?

To begin with, the region has seen unrelenting weather upturns. First, unseasonal rain and hail in February and March last year, followed by drought when the monsoon failed. This year, there was, another cycle of unseasonal rain and hail. The result: acres and acres of standing crops laid to waste.

Among those driven to despair was Sandipan Babar, a farmer in his late 30s from Dhanuri in Osmanabad’s Lohara block. The scorching heat of the summer of 2013 ruined his first crop of sugarcane. He borrowed Rs 30,000 to get past those losses. Taking hope from the high prices of onions, he decided to sow the vegetable, only for the prices to suddenly drop to Rs 5 per kilo, far less than the cost of sowing them.

That proved too much for him. On January 10, 2014, Babar went to his field and killed himself.

Two months later, while the family was still mourning his death, a hailstorm wiped out the last crop he had sowed: jowar and mangoes.

In their home, his wife, Shaira, brought out pictures from better times: when the couple migrated to Mumbai soon after their marriage in 1999 and Sandipan took up a job as a bellboy at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in Colaba.

Shaira Babar holds up a photo of her husband Sandipan in Mumbai.

Initially, the city felt welcoming, but then the struggle began. “They said there was no future for him in Mumbai as he had only passed his third standard,” said Shaira, who is also from Dhanuri. In 2007, they returned to the village to tend to the family’s ancestral two-acre farm. “He had lost the habit of working in the fields while he was in Mumbai, but he still did his best,” she said.

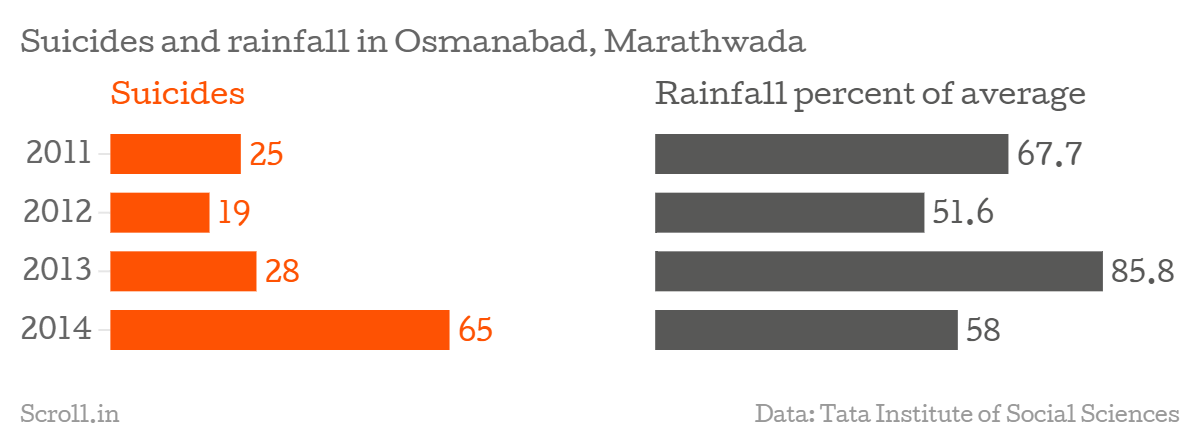

But even the best is perhaps no longer good enough in Osmanabad, one of the driest districts in the state. Like other districts in Marathwada, it has seen a sharp increase in the number of suicides. The suicides have not always risen in tandem with bad weather. In 2013, despite low rainfall the previous year, the number of suicides was still far lower than those in 2014, which followed a year with much higher rainfall. The maximum number of suicides are usually reported in March, when it is time to repay loans.

The problem then lies deeper than weather.

Agrarian experts say there is a tangled web of factors: sinking groundwater levels, dependence on water-sucking cash crops such as cotton and sugarcane, mismatched input and output costs, unstable crop prices at the market, a lack of insurance.

“Why are suicides happening only in farmer families?” asked Naval Kishore Ram, the District Collector of Beed. “People say there are reasons such as liquor consumption. [But] even the rich consume liquor, they don’t kill themselves. The problem is that we don’t see an end-to-end process to make farmers safe. There is no safety net, no support system of insurance cover.”

According to Ram, most suicides in Beed are linked to cotton, a commercial crop which has high input costs coupled with high market risks. In recent years, the introduction of Bt cotton had exacerbated the risks, he claimed. Unlike traditional cotton, for which farmers can save seeds from the harvest, for Bt cotton, they depend on seed companies. This has changed lending patterns. “Farmers are taking loans right from borrowing seeds to taking the crop to the market,” he said.

But returning to traditional cotton is not an option. “Traditional cotton allowed them to grow other crops alongside,” said Ram, “but it gives very little money.”

Ram offered another reason for the suicides: the islands of lushness in an arid region.

Sanjay Gondge, brother of Avinash, and two of his friends stand in the dry remains of their field. Behind them is a neighbour's irrigated sugarcane field.

Of Marathwada’s 565 suicides in 2014, Beed has seen the most, 152. Almost a third of these people come from lush Georai, which has the Godavari flowing through it and remains green even as vast areas in Marathwada remain parched.

“Places like Ashti and Patoda are arid so people already know that they have to struggle hard,” said Ram.“[But] Georai has more rainfall, so now people are not able to absorb the shock [of poor rainfall].”

This harsh assessment does not square with farmers' experiences – they are dying not because of a lack of rain, they say, but because they do not have the resources to survive a setback.

Twenty kilometres away from Avinash’s village in Georai is Jategaon, where three months after his death, another 23-year-old, Sakharam Chavan, killed himself. Sakharam was to have been married on March 10. His family had already accepted a dowry of Rs one lakh from the prospective bride. But a combination of loans and losses on his farm led him to this final step.

“Nature is not with us, the rain is not with us, even the prices are not with us,” said his mother, Janabai Chavan, as she prepared to take the family’s shrunken harvest of onions to the market. Damaged crops and harvest losses tend to push up prices of onions for consumers in the city, but for small farmers like the Chavans, who need to sell the produce soon to recoup their investments and repay loans, there aren’t any gains to be made during years of shortfall.

Janabai Chavan, mother of Sakharam, with a photograph of her son.

The final straw for the families is the struggle to get compensation from the state. Avinash Gondge, Sandipan Babar and Sakharam Chavan all suffered agricultural losses, but only two of them, Babar and Chavan, have been considered eligible for the Rs one lakh compensation that the Maharashtra government gives to the families of farmers who have ended their lives.

Why is Avinash being left out of Maharashtra government’s compensation scheme, despite the disturbing image that was taken with the express purpose of documenting his death?

The next story looks for an answer.

This is the first in a series of reports on the agrarian crisis in Marathwada.