Memon came back to India from Pakistan to surrender and brought with him proof of Pakistan’s involvement in the bombings. This fact was pointed out by none other than B Raman, the person who coordinated the operation for Memon’s return from Karachi. At that time, Raman headed the Pakistan desk at the Research and Analysis Wing, India’s primary foreign intelligence agency.

“The cooperation of Yakub with the investigating agencies after he was picked up informally in Kathmandu and his role in persuading some other members of the family to come out of Pakistan and surrender constitute, in my view, a strong mitigating circumstance to be taken into consideration while considering whether the death penalty should be implemented,” Raman wrote.

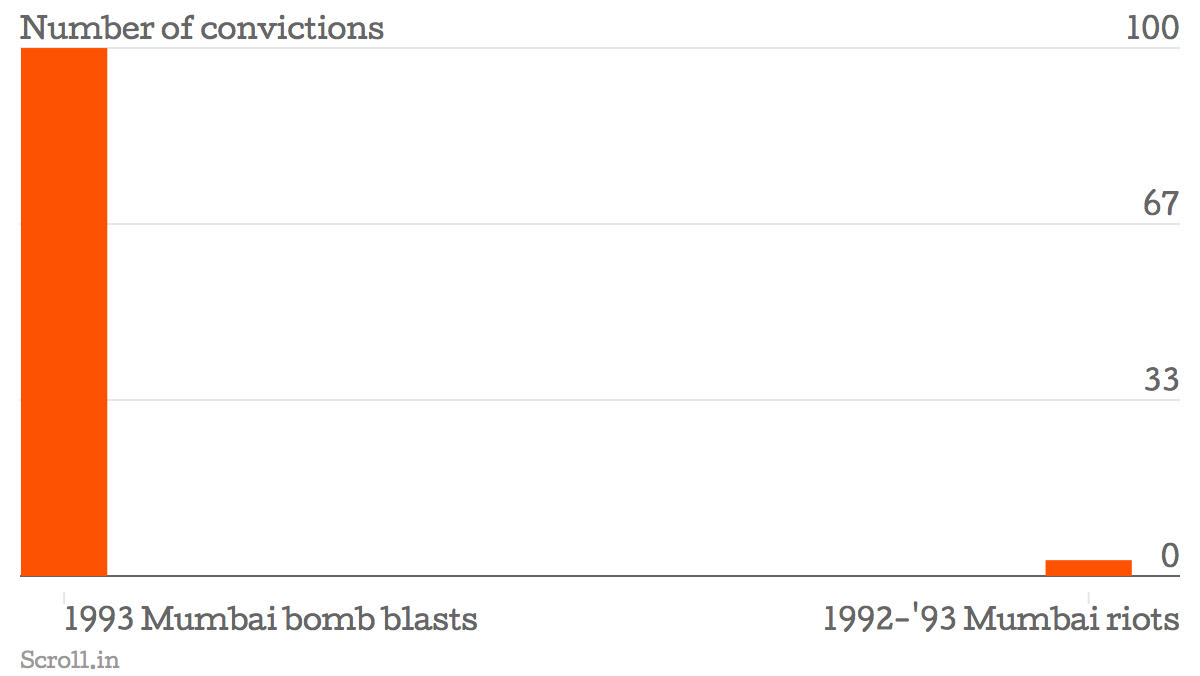

Memon’s death sentence is just one questionable decision. The partisan manner in which India’s justice system works can be seen from the following chart:

As many as 100 people have been convicted for the 1993 Bombay serial blasts which took 257 lives. However, in the 1992-’93 Mumbai riots, an act of mass violence that killed 900 people, just three convictions have been achieved.

Even these three were for the relatively minor charge of hate speech and only carried jail time of a year. There were no convictions for the numerous incidents of murder, rape or arson.

What explains this massive gulf?

Two approaches

The answer lies in the Indian state’s approach to the two crimes. The Maharashtra government mostly didn’t bother about punishing the people who led the anti-Muslim massacres of December 1992 and January 1993. All it did was appoint a commission – the Indian politician’s go-to answer when he wants to do nothing.

When this commission, headed by Justice BN Srikrishna, did submit its report, it was damning. The report described Shiv Sena chief Bal Thakeray’s role as that of a “veteran General” who “commanded his loyal Shiv Sainiks to retaliate by organised attacks against Muslims”.

The process of damning, sadly, never moved on to any damnation: no action was taken on the Srikrishna Report. Thackeray was, in fact, given a state funeral – Maharashtra’s Congress government maybe taking the “General” bit literally

Not only Thackeray, the police barely pursued any riot cases. In fact, as many as 60% of cases were summarily closed with the remark “true but undetected”. Later on, the Srikrishna Commission found that even blindingly obvious cases, such as when victims had named assailants who were their neighbours, were ignored and dismissed.

In contrast, the blasts were prosecuted with rare vigour. A special investigative team was appointed and the stringent Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act was applied liberally.

The results are borne out by the number of convictions.