If these plots are officially recognised as slums, they would be eligible for redevelopment as SRA projects. Residents losing their homes would be given 269-sq ft apartments in the new complexes, but the scheme would also open up prime sea-facing properties to the commercial real estate market.

The SRA’s notice to the residents, however, conveniently overlooks the fact that Worli Koliwada cannot be declared a slum, because it is a recognised fishing village and gaothan (urban village) inhabited for generations by Kolis and Agris, some of Mumbai’s original settlers. "Current development rules for gaothans don't allow for high constructions," said Alphi D'Souza, spokesperson of the Mobai Gaothan Panchayat, a non-profit group looking into the welfare of Mumbai's many urban villages.

In addition to being a gaothan, Worli village is also classified as Coastal Regulation Zone III, whose rules do not allow further construction on coastal properties.

For some of Worli village’s older residents, these are the central arguments in their objections to the SRA’s notice. But the demography of the Koliwada has changed significantly in the past few decades, and many of the newer residents have their own personal reasons for opposing slum rehabilitation schemes in the village: while some are worried about losing the illegal tenements they’ve built in the area, others would rather bargain for a redevelopment scheme more beneficial than an SRA projects.

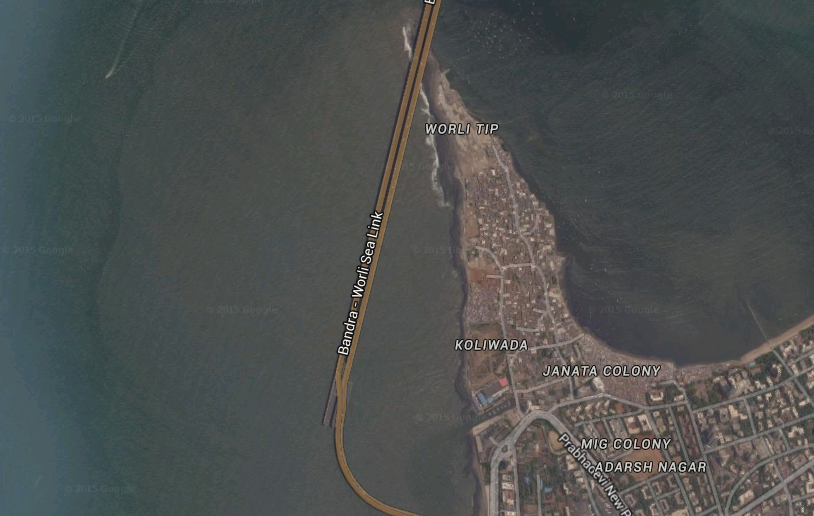

Worli Koliwada on Google Maps.

‘The land belongs to original residents’

Seen on a map of Mumbai, Worli Koliwada juts out as a narrowing strip of land protruding from the city’s coast towards the middle of the Bandra-Worli sea link. Two parallel roads lead into the depths of the village and on either side of them, small homes of varying sizes are crammed beside each other, often blurring the lines between slum-style living and an urban village.

At the tip of the village is the small 17th century Worli Fort, a heritage monument whose inner courtyard has now been taken over by a local gymnasium. The Fort offers an elevated view of how densely populated the 65-acre Koliwada’s is.

“On record, the village has 457 homes, most of them belonging to Kolis and Agris, the original owners,” said Vilas Worlikar, a retired fisherman and prominent activist serving as an office-bearer in various associations and societies in the village. “But on the ground, the actual number of homes today must easily be more than a thousand. The population of the village is probably more than a lakh.”

A view of the Koliwada from Worli Fort.

Some of the population rise is visibly because of a few actual slums that have mushroomed on open land fisherman once used to dry fishes. “Even that land technically belongs to us, the original residents,” said Worlikar. “We let people build huts there because the city has very little space and they needed place to stay.”

‘Few Kolis are left here today’

But the main reason behind the changing demographics of the village is that many of the original residents are renting out their properties to new tenants and have even built additional homes to rent out.

“There are very few Kolis left in the village today – most of them have moved out and rented their properties to others,” said Kaviraj Thadani, a food entrepreneur whose family has been living in Worli village since the 1950s. The newer residents, he says, are a cosmopolitan mix of people from all over India. “Because the rents are fairly affordable, a lot of people who work around Worli choose to live in the village.”

A street in Worli village.

The problem, according to Worlikar, is that a lot of the additional tenements the original residents have built are illegal and not on record with city authorities. If those plots are redeveloped under the SRA scheme, the illegal homes will not be accounted for when original owners are given new homes in place of their old ones.

Some residents were candid enough to admit this, but did not wish to be identified. “I live in the central part of Koliwada, but some of the other houses in the village are also mine, if you know what I mean,” said a middle-aged Koli resident. “If we have redevelopment, I would lose my other houses.”

‘We can’t live like this anymore’

Worlikar is clear that neighbourhoods in his village cannot be legally classified as slums. But he is not opposed to redevelopment in itself. “What we need is a form of cluster redevelopment designed on our terms, incorporating all our needs,” he said. “We would need schools, space to dry and store fish and bigger houses for all residents who have been living here for more than 15 years.”

The younger generation of Koliwada residents, meanwhile, are preoccupied with another concern: improving their standard of living.

“We know that the older residents who still work in fishing don’t want their homes to be developed, but we can’t live in this manner forever,” said Akshay Parab, a 21-year-old telecom sales executive whose family has been staying in the village since 1992, on cessed property rented out by Koli landlords. “There are serious sewage problems in the village, there is a lack of space and the biggest problem is the toilets. I have to use a common toilet with neighbours and I don’t want to do it anymore.”

Parab and his friends are waiting for a redevelopment opportunity in Worli village, but despite their desperation, they claim they will oppose a slum rehabilitation scheme. “The SRA will only give us 269 sq ft in a new apartment, but we want more,” said Parab. “We are willing to go with any builder or scheme that gives us more space to live in.”