India has seen its climate change since the 1950s, with ambient air temperature rising, monsoon precipitation declining and droughts becoming more frequent. In recent years there have also been a number of weather extremes – from destructive flash flood in Uttarakhand in 2013 to the heat wave in Andhra Pradesh this summer to the heavy rainfall and flooding in Chennai over the last few weeks, all highly damaging to life and property.

Climate change projections show an increase in extreme weather events with a rise in global temperatures. The main goal at the Paris conference is to agree on a set of actions to mitigate carbon emissions so that atmospheric warming can be restricted to 2 degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels. So far, the world has warmed about 0.8 degrees Celsius. The less successful mitigation is, the more the world, and especially developing countries, will have to adapt to the rising sea level, changing agricultural systems, disease and wild weather.

The new report called Climate Change and and India Adaptation Gap (2015) – A Preliminary Assessment produced jointly by researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad and the think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water, analysed extreme weather events in the last 14 years to find that there were 131 instances of major flooding, 51 instances of cyclones and 26 instances of heat and cold waves and three instances of major drought. The losses from these events tallied up to $51 billion, the biggest damages coming from floods.

The risks from a changing climate are getting worse and the actions to tackle it continue to be inadequate creating what's called an adaptation gap. “The adaptation gap is very dynamic,” said Vimal Mishra, assistant professor of civil engineering at IIT Gandhinagar and one of the authors of the report. “Suppose you have planned for a weather event that occurs once in 100 years or once in 50 years but all of a sudden you get an event that is ten times that event. This is a gap of adaptation.”

As the severity of climate events increase, so will the money required to deal with weather extremes and for agriculture, public health, water resources and infrastructure.

India hasn’t been taking the climate threat lightly. The report estimates that while India’s overall budget has increased four times in the past decade, its commitment to adaptation measures has actually increased five times and stands at about $33 billion in 2014-'15 or roughly 2% of India’s gross domestic product.

In addition to this are 21 government schemes directly linked to climate change adaptation and the newly set up National Adaptation Fund, which has committed $55.6 million for adaptation needs in different sectors. State governments are also making commitments for adaptation under their respective State Action Plans for Climate Change, which in 2013-'14 totalled close to $48 billion.

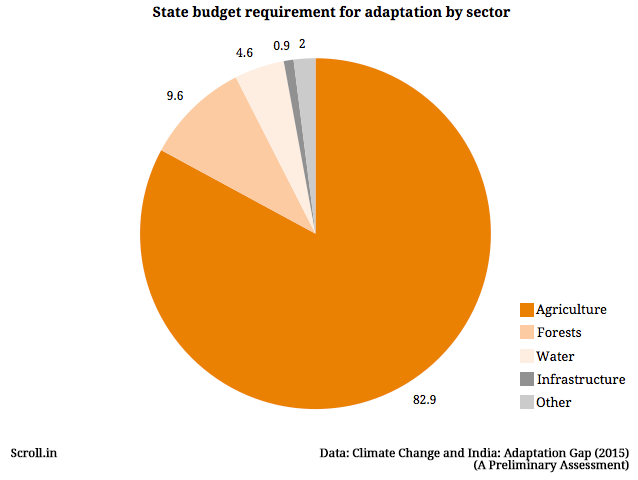

Despite all this money being thrown into the adaptation kitty, the requirement is at least three times more. The cumulative demand by India’s states according to their action plans is at least $168 billion by 2030, about 83% of which is needed to gear agricultural systems towards extreme weather.

This year's drought, for example, did not affect many states in India but it hit Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka farmers hard. Adapting financially for more droughts means having money to provide financial aid to farmers and also to account for inflation associated with crop failure.

Since 1993, India has received international aid via 38 projects from bodies like the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, the Global Environment Facility and the United Nations Development Programme. But this financing is a little more than 3% of India’s climate change expenditure.

The new report suggests that previous attempts to quantify the adaptation gap have underestimated the adaptation requirements. For instance, an Asian Development bank report said that India would need to spend about $206 billion on adaptation strategies, but the new report says that $178 billion will have to be spent on bolstering and building new infrastructure alone.

With current expenditure for adaptation activities at $92 billion and losses from weather disasters at another $5-6 billion, the report estimates that with a shift towards greater climate risk the financing requirement for adaptation in India will be $360 billion by 2030. Even this might fall short.

“We estimate on the basis of what the government is spending,” said Mishra. “Is the government spending to fill the gap accurately or is it just what the government is in a position to spend?”

India will also need a whole lot of technology to be transferred from the West to adapt quickly and smartly to climate change. Some of these technologies could be climate models for India, flood proofing, floating agricultural systems, desalination plants, appropriate genetically modified crops, electric vehicles and smart grids. Such measures along with knowledge and capacity building could end up in an adaptation investment of $1 trillion.

Said Mishra, “$1 trillion is the high-end ball-park number which India may need in the worst case scenario in 2030.”

So far, developing countries have been hard-pressed for finance from the developed world. The Green Climate Fund that was supposed to raise $100 billion annually from 2020 has received a measly $10 billion and that too only in pledges and not actual money. At Paris, India’s negotiators will fight for a legally-binding deal for rich countries to fulfil their financial obligations, to be decided on the basis that developed countries are historically responsible for climate change by their consumption of fossil fuels in their long years of industrialisation and that poor countries now need their carbon space to develop.

"Developed countries should take some sort of responsibility," Mishra said. "India is agreeing to reduce 30%-35% emissions intensity and that is a very big commitment if we want to e energy secure and keep developing the way we want to develop."