India has boosted its nuclear triad – nuclear-armed strike aircraft, land-based inter-continental ballistic missiles and sea-based submarine-launched ballistic missiles – and now has a strong nuclear deterrence capability vis-a-vis its nuclear-armed neighbours.

“Such [a triad] essentially increases the deterrence potential of the state’s nuclear forces,” write Group Captain Ajay Lele (retd.) and Parveen Bhardwaj of the Institute of Defence Studies and Analysis, a New Delhi think-tank.

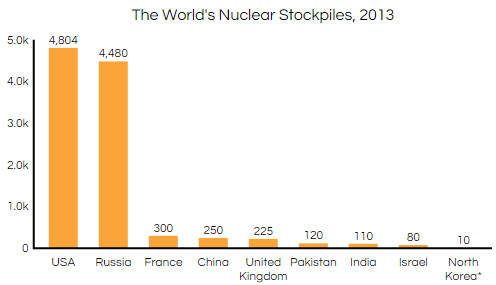

Given that a nuclear warhead with a yield of 1 megaton can destroy almost 210 sq km, roughly three times the size of south Mumbai, it is largely inconsequential if Pakistan has 10 more warheads than India or China has 140 more, as data released by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, a US advocacy that tracks global nuclear arsenals, reveals.

Pakistan has also been recognised as having the world’s fastest growing nuclear arsenal, which, according to this New York Times editorial, is turning South Asia into a “troubled region with growing nuclear risks”.

Source: Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists; As of 2013

Having more warheads than your opponent does not necessarily translate to greater security.

This is largely because nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction, meant primarily to scare and deter, usually ending in a situation of strategic stalemate between countries that possess nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons were used only twice in battle, 69 years ago, dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and never since.

The possibility of “mutually assured destruction”, or MAD, as it is commonly known,also prevents their use in the subcontinent.

The Indian nuclear triad grows stronger

India’s nuclear-strike capability is strong because it has multiple strike aircraft, such as the nuclear-capable Anglo-French Jaguar, French Dassault Mirage 2000 and the Russian Sukhoi 30 MKI aircraft (being upgraded to carry the nuclear-tipped supersonic Brahmos missile).

Its land-based ballistic missiles include the Agni V with a range of 5,000 km, which means it can reach all of China. The Agni V can be launched from a mobile transporter or a special railway wagon, so it can be kept hidden and moved at will, according to this report.

The third component of the triad is under development, nuclear-powered Arihant class submarines that are capable of launching the 700-km range K-15 Sagarika ballistic missile and the 3,000-km range K-4 ballistic missile.

China possesses a nuclear triad, but Pakistan, which lacks sea-launch capability, does not.

No first use: India’s Nuclear Doctrine

No first use. That’s the declared essence of India’s nuclear doctrine, adopted in January 2003.

It says India will use atomic weapons “in retaliation against a nuclear attack on Indian territory or on Indian forces anywhere”. The retaliation, said the report, “will be massive and designed to inflict unacceptable damage”.

India also declares it will not use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states. According to the draft of the nuclear doctrine, India needs “sufficient, survivable and operationally-prepared nuclear forces”.

“Used in conjunction with the concepts of 'No First Use' and 'Non Use' against non-nuclear weapon states, it clearly indicates that India envisages its nuclear weapons as only a deterrent merely for defensive purposes and not as a means to threaten others,” writes Satish Chandra, former deputy national security advisor.

Why India built nuclear weapons

The world first witnessed the destructive capability of nuclear weapons in 1945, when the US bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing approximately 2,00,000 people. The event was a reference point for debates on the political nature of nuclear weapons.

Under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, India pursued a policy of aversion toward nuclear-weapons technology. However, with the assistance of the United States and Canada, India actively pursued its nuclear-energy programme.

The 1962 Sino-Indian war, and China’s decision to conduct nuclear tests in 1964, led Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri to authorise the theoretical framework for what was – ironically – termed a Subterranean Nuclear Explosion for Peaceful Purposes.

The SNEPP culminated in Pokhran I, India’s first ‘peaceful’ nuclear explosion on May 18, 1974, when Indira Gandhi was prime minister.

While the yield of the test has been the subject of debate among academicians, the test proved India’s capability to weaponise nuclear technology.

The plutonium used for the device was obtained from the Canada-India-US Research Reactor (heavy water for the reactor came from the US), according to the Federation of American Scientists.

This led to international sanctions on India, which severely hampered India’s nuclear weapons programme. More importantly, this event led to the creation of the Nuclear Suppliers Group.

After a 24-year pause, India conducted five nuclear weapons tests in May 1998 when Atal Behari Vajpayee was prime minister. The tests were followed by a self-declared moratorium on further nuclear tests.

Pakistan successfully conducted its first nuclear weapons tests less than three weeks later.

This article was originally published on IndiaSpend.com, a data-driven and public-interest journalism non-profit.