In 1927, Carl Jung stood in his Zurich home, gripped by a vivid dream of a mandala, a radiant circle of intricate patterns, pulsing with meaning, which he later described in Memories, Dreams, Reflections as a “Window on Eternity”.

This vision, a map of the psyche’s quest for wholeness, became a cornerstone of his theories, deeply enriched by his 1938 journey through India’s spiritual heartland.

July 27 was Jung’s 150th birth anniversary. In today’s fractured world, Jung’s ideas, rooted in archetypes, the collective unconscious and the integration of opposites, feel more vital than ever.

Balance and meaning

Born in 1875 in a quiet Swiss village, Carl Gustav Jung was a psychiatrist, philosopher and mystic who saw the human psyche as a vast, dynamic universe. Unlike his mentor psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who viewed the mind as a battleground of repressed desires, Jung believed it was a living system striving for balance and meaning.

Jung’s core concepts – individuation, archetypes, the shadow self, and the collective unconscious – were deeply influenced by the ancient wisdom he found in India’s temples, texts and scholars.

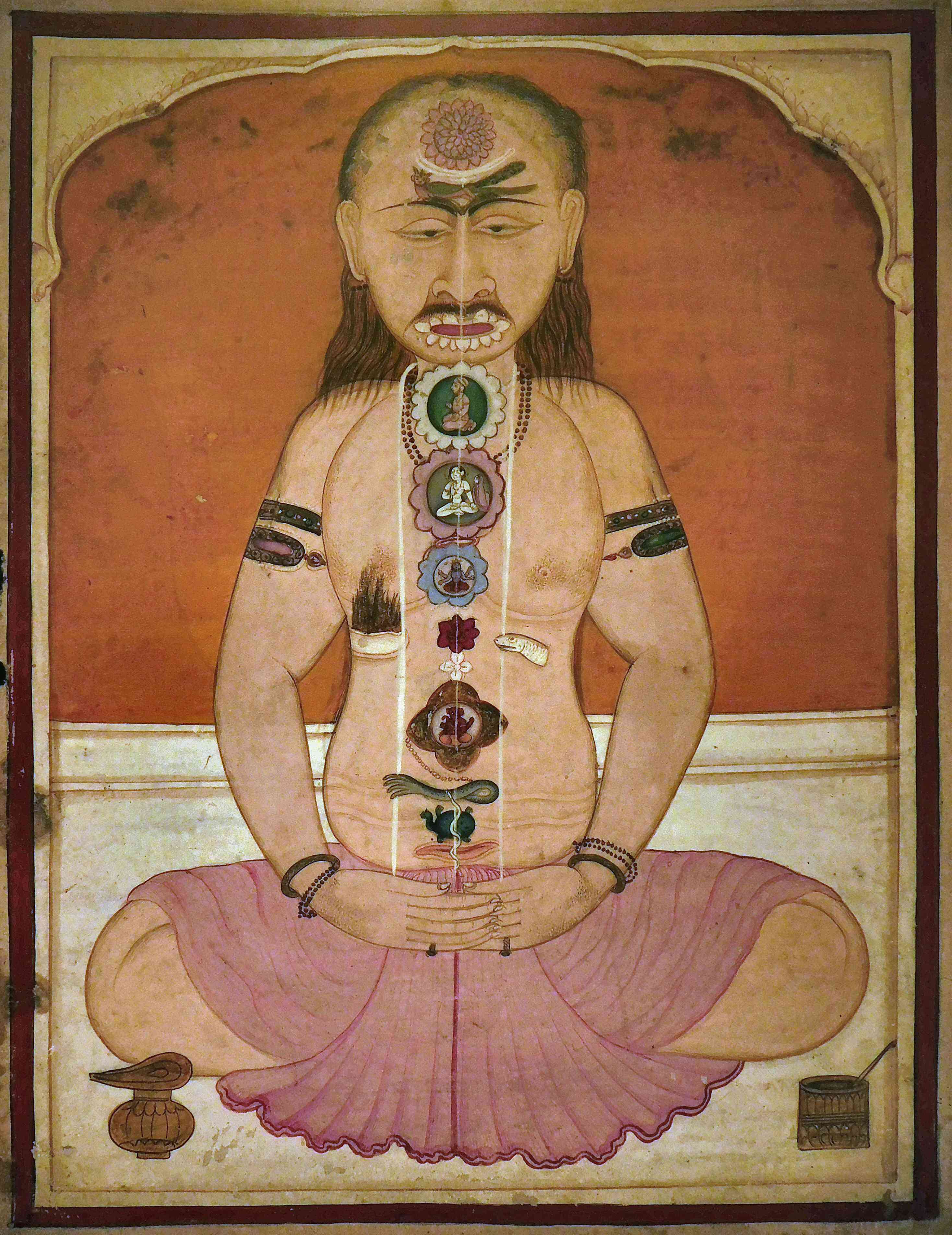

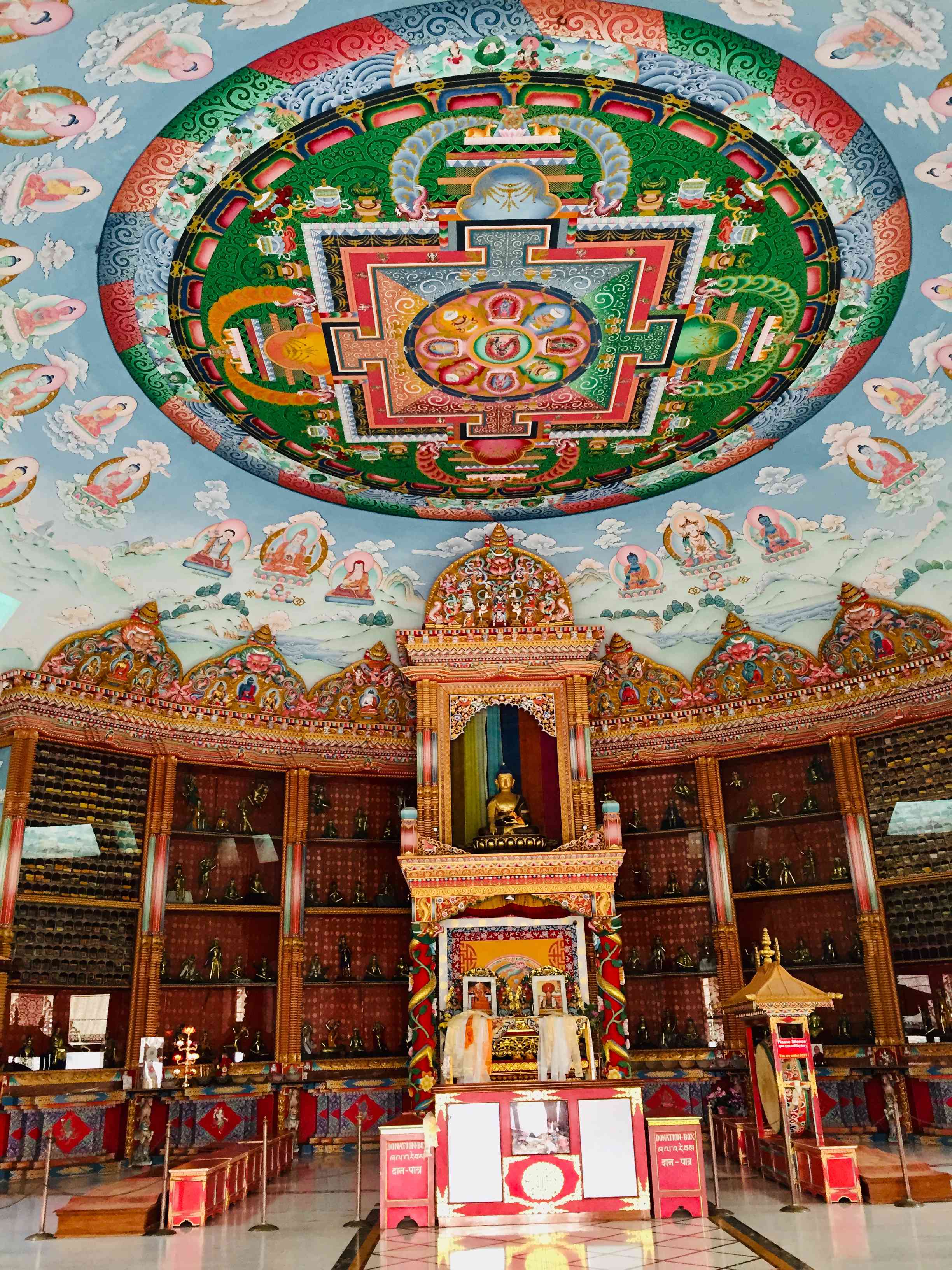

In Zurich, Jung’s mandala dream echoed the sacred circles he saw in Hindu and Buddhist art. In these traditions, a mandala is far more than a geometric design. In Hinduism, it represents the cosmos, a map of divine order, often used in rituals to invoke deities like Kali or Vishnu.

In Buddhism, particularly in Tibetan practices, mandalas are meditative tools, guiding the practitioner toward enlightenment by symbolising the universe’s unity. Jung saw the mandala as a universal symbol of the psyche’s integration, a bridge between the conscious and unconscious.

Jung’s fascination with India deepened as he engaged with its spiritual symbols. In Calcutta, he met Surendranath Dasgupta, a renowned scholar of Indian philosophy, with whom he had deep discussions about the Upanishads and kundalini, the coiled serpent energy at the base of the spine.

In Tantric traditions, kundalini’s awakening is a transformative ascent, uniting the individual with the divine. Jung saw parallels with his idea of individuation, the lifelong process of integrating the psyche’s fragmented parts into a whole. He was equally struck by the Shiva-Shakti dynamic – the cosmic dance of masculine and feminine energies.

In Tantra, Shiva represents pure consciousness, while Shakti is the dynamic force of creation. Jung linked this to his anima and animus: the inner feminine and masculine polarities that must be balanced for psychological wholeness.

At the Konark Sun Temple, Jung stood before carvings of cosmic cycles and erotic figures, sketching them in his notebook. The raw passion depicted in the sculptures, blending the sacred and sensual, mirrored his concept of the shadow self, the hidden, often uncomfortable aspects of the psyche we must confront. He later wrote that Konark’s imagery spoke to the “living reality of the psyche”, where opposites like light and dark coexist.

In Bhubaneswar, he sketched temple carvings of Kali, the fierce goddess of destruction and renewal. Kali’s dual nature – terrifying yet transformative – resonated with Jung’s view of the shadow as both destructive and creative. He saw her as an archetype, a universal symbol of the psyche’s power to devour and renew.

Jung’s encounter with the Tibetan Book of the Dead during his Indian sojourn further deepened his theories. This Buddhist text, a guide for navigating the Bardos, or transitional states, between death and rebirth, fascinated him. He saw its descriptions of visions and deities as manifestations of the collective unconscious, a shared reservoir of human experience that transcends individual minds.

The book’s emphasis on facing one’s inner demons aligned with Jung’s belief that confronting the shadow is essential for growth. He later wrote that the Tibetan Book of the Dead was a “psychological commentary on the unconscious”, a bridge between Eastern spirituality and Western psychology.

In Delhi, Jung listened to Vedic hymns at a banquet, struck by their resonance with his concept of synchronicity – meaningful coincidences that reveal the psyche’s connection to the cosmos. These moments cemented his belief that his theories were not new but echoes of ancient wisdom, reframed for a modern world.

Jung’s split with Freud, around 1913, was a pivotal moment that allowed him to pursue these ideas. Freud saw the psyche as driven by personal trauma and sexual instincts, with dreams as coded messages of repressed desires. Jung disagreed, arguing that dreams tapped into the collective unconscious, a shared layer of human experience filled with archetypes like the “Hero”, who drives personal growth, or the “Mother, the lifegiver who symbolises one’s origin.

Their breakup was painful, but it freed him to explore the mystical and cultural dimensions of the psyche.

Jung in the era of polarisation

Why do Jung’s ideas resonate so powerfully in 2025? In an era of mass polarisation, his emphasis on integrating opposites offers a path forward. The shadow self, those parts of us we deny, is especially relevant. Social media amplifies our curated personas, but it also casts shadows – anger, fear, or shame we project onto others. Jung’s call to face the shadow, to own it rather than vilify it, is a tool for healing. The collective unconscious speaks to our longing for connection, reminding us that beneath our differences lies a shared humanity.

Jung’s influence is undeniable. His ideas shape modern psychology, from therapy to personality tests like the Myers-Briggs, which claims to categorise personality types.

Pop culture embraces his archetypes and mindfulness apps feature mandalas as tools for calm. In a world grappling with the rise of artificial intelligence, climate crises, and cultural divides, Jung’s focus on inner transformation feels urgent. He believed that changing the world starts with changing oneself, a message that cuts through the noise of this era.

Shadow work, Jung’s boldest call, urged confronting the psyche’s repressed elements. He saw it as a moral necessity for growth. Jung’s shadow encompasses the darker aspects, anger, fear, or shame, that we deny or project onto others. Shadow work, his term for acknowledging and integrating these traits, aims for wholeness.

In India, he saw parallels in Tantra’s embrace of life’s dualities, as seen in Kali’s destructive yet regenerative imagery, which accepts all existence. Today, shadow work informs trauma therapy, where techniques like journaling or guided visualisation help process suppressed emotions, reclaiming fragmented selves for healing. Tantra’s fearless acceptance of contradictions reinforced Jung’s belief that embracing the shadow fosters authenticity. Freud suppressed undesirable impulses but Jung advocated their integration.

Yet Jung wasn’t flawless. Critics note his tendency to romanticise Eastern traditions, sometimes missing their nuances. His writing could be dense, almost esoteric, unlike Freud’s clearer prose. Still, his willingness to grapple with the unknown, blending science with spirituality, made him a pioneer. He once said, “The shoe that fits one person pinches another; there is no recipe for living that suits all cases.” This embrace of individuality is why his work endures.

On Carl Jung’s 150th anniversary, his Mumbai mandala dream remains a profound symbol of the psyche’s balance of opposites: Kali’s cycle of destruction and renewal, Kundalini’s ascent, and the union of Shiva and Shakti. In 2025, as algorithms shape desires and divisions and challenge our humanity, Jung’s call to self-reflection feels revolutionary.

Infused with Indian wisdom, his theories are vital tools for today’s world, reminding us that the path to self-discovery also connects us to one another – a truth as alive now as it was all those years ago when he dreamt of the mandala in Zurich.

Vikram Zutshi is a writer and filmmaker, formerly a real estate developer and consultant to Tech startups, based in California.