When Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated two metro lines in Mumbai in 2023, Yaakshi Dave thought the sweat and grind of her commute to the office would end.

The 21-year-old graphic designer eagerly hopped on to the swanky coaches of the metro, hoping to travel 15 km in the city’s western suburbs in air-conditioned bliss.

But mid-way in the journey, she found that not only did she have to change from one metro line to the other, she had to exit the station and navigate dense traffic to do so.

The two metro lines did not intersect. There was no interchange station.

For 23 minutes of air-conditioned metro travel, Dave had to walk a total of 20 minutes – to get to the metro station and to switch lines. Tired of the exertion, she gave up on metro travel and went back to commuting by bus.

She is not the only one. Data shows Mumbai commuters are staying away from the metro network, belying hopes that it would take the load off local trains and ease traffic on the roads.

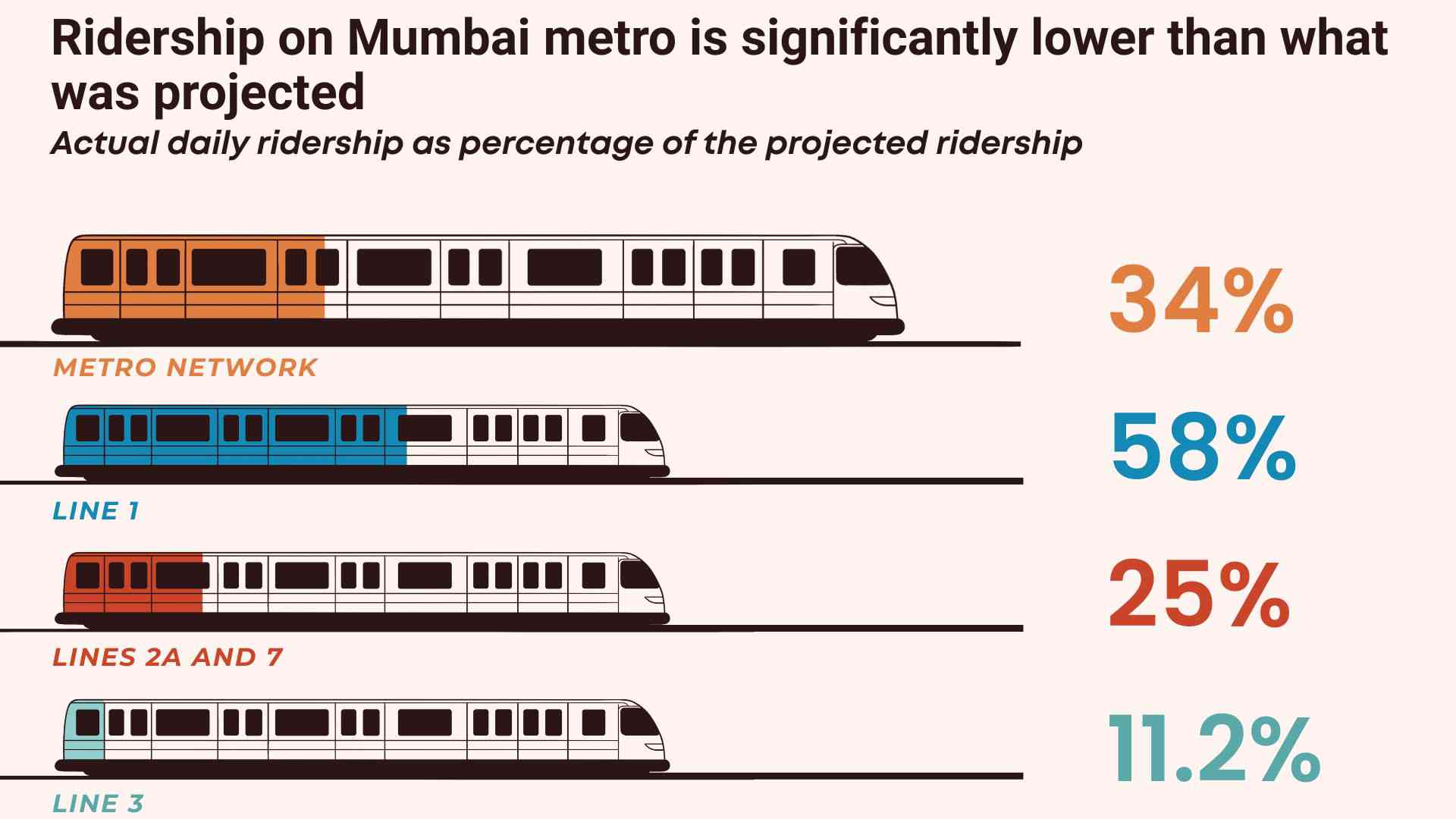

Lines 2A and 7 between Andheri and Dahisar, for instance, have only reached 2.05 lakh ridership per day – 25% of the projected ridership, data till mid-June shows.

The latest addition to the network – the Aqualine which connects Aarey Colony in the north to Worli in central Mumbai – has only 45,000 daily passengers, till mid-June, a tenth of estimated daily ridership,

The total daily ridership on all four metro lines is less than seven lakh, against an estimate of 18.84 lakh.

The Mumbai metro network is being built at a staggering cost of more than Rs 90,000 crore, which is escalating with every year of construction delays. Its failure to attract riders, experts say, reflects a wider crisis in India’s urban transport landscape – the focus of this three-part series.

Connectivity trouble

Mumbai currently has four metro lines run by three operators. Not only do they lack seamless interconnectivity, the lines don’t even share common ticketing.

Every morning that Sahil Gupta, an engineer, takes the metro to work, he goes through three rounds of security checks, ticket scans and baggage scans.

An autorickshaw from home takes him to Malad station in the western suburbs where he boards metro line 2A, alighting at DN Nagar. Here, he exits the station, takes a foot overbridge to line 1. He repeats ticketing and security before travelling to Marol, where he crosses the road, and goes through the same drill again before boarding his third and final metro line 3 to get to the airport.

“The system is complicated,” Gupta said. “I have to buy three tickets and go through three scans.”

An official from the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority defended the system, saying it was natural for each metro operator to undertake their own security checks.

In June, the National Common Mobility Card came into use in Maharashtra. The contactless card is meant to streamline travel across all modes of public transport in India. However, in Mumbai, it only works on metros and buses.

A MMRDA official said the monorail has a closed-loop ticketing system, which means it requires dedicated cards and will not accept interoperable cards used on other modes of transport. The common mobility card is not integrated with the suburban railway system.

Last mile chaos

Mitesh Tomani, a 24-year-old college student, said he struggles every day to look for an auto or a bus from Aarey-JVLR metro station to his college, SDA Bocconi Asia Center, in Hiranandani Gardens.

Tomani first takes a bus from his home in Worli to Acharya Atre Chowk metro station, then he hops on to line 3, known as the Aqualine, and travels till the last station in Aarey colony. From there, if he is lucky to find a bus or an auto rickshaw he travels further for about 4 km to his college. The entire journey takes over an hour and costs Rs 250.

“The metro makes the ride comfortable,” he said. “But little thought has been put towards what passengers can do once they step out of the metro.”

There are four buses from the bus stop near Aarey metro station towards Hiranandani where his college is. Most days, he gets tired of waiting for a bus on the desolate stretch. “The frequency of buses is poor,” he explained.

He ends up spending Rs 70-Rs 100 on an autorickshaw ride one way. “Even for that I have to wait,” Tomani said. “Not many autorickshaws pass through this road. The metro station is new.”

Transport experts say this is a common experience, which they attributed to a lack of planning.

“There are bus stands and dedicated lanes for autorickshaw outside railway stations, but nothing similar can be found outside metro stations,” said AV Shenoy, co-founder of the Mumbai Mobility Forum, a think-tank that focuses on public transport.

He pointed out that Mumbai had different operators for local trains, BEST bus and metros, all of which work in isolation. “Ideally new bus routes should be started around the new metro stations,” he said.

For instance, for most of its length, metro line 7 runs parallel to the Western Express Highway. When passengers exit the metro stations, they emerge on the highway where moving traffic makes it impossible for auto rickshaws to halt for long. Even bus stops are not located close to the metro stations.

“There is little thought put into how people will get to the metro station or leave it,” said transportation analyst Sudhir Badami.

Back in 2008, the state government had formed the Unified Mumbai Metropolitan Transport Authority to bring all modes of public transport under one umbrella. But Shenoy said the chaos outside metro stations showed that the authority had failed to do its job.

A former official of the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority, which operates metro lines 2A and 7, claimed that the agency had actually attempted to ensure that it was integrated with other modes of transport.

“For some stations, we tried to create a space for buses to stop and autos to ply,” he said, requesting anonymity since he was no longer authorised to speak to the media. But for the efforts to succeed, he said, “BEST has to ensure they create [bus] stops near metro stations and auto-unions must create a service of share-autos from there.”

The MMRDA is now working on connecting some of its metro stations to local railway stations.

Metro users, however, point out that the problem isn’t limited to the lack of last-mile connectivity. Exiting metro stations itself can be a hazard – there is no safe pedestrian space outside.

A survey by the Walking Project, a citizen initiative in Mumbai, found that at least four metro stations on line 2A had no footpath at the exits.

“Lack of holistic planning forces ridership to the lower side,” said Walking Project’s programme manager Vedant Mhatre. “London has much wider footpath access to stations.”

Steep cost

The Mumbai metro network has been under construction for over a decade.

The first metro line connecting Versova and Ghatkopar in the western suburbs was inaugurated in 2014. The per kilometre cost of building it was Rs 206 crore in 2012, according to data from the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority.

By the time the MMRDA began building metro line 7 and 2A, the cost had escalated to Rs 359 crore per kilometre.

“At one-tenth the cost, buses would have ferried the same number of people,” said transport expert Badami, who has been advocating a bus rapid transport system as the solution for Mumbai’s traffic woes.

Eighty-two percent of Mumbai’s population lives within 5 km of their workplace, according to a 2008 survey by the Mumbai Urban Transport Project. “That leaves 18% who would ride a metro for long-distance travel,” Badami said.

However, he noted that “with 50% of the population residing in slums, not everyone can afford metro fare”.

It costs Rs 10 to travel 40 km by local trains. On the metro, the cost is Rs 80 for the same distance.

Transport expert Shenoy questioned the utility of the Mumbai metro in its current form. It is too expensive for Mumbai’s working class, he said, who continue to take the local trains. And those who can afford the metro are unlikely to use it because of the lack of convenience. “Why would they walk so much?” he asked.

The Maharashtra government plans to eventually build 14 metro lines over 337 km with 225 stations in the Mumbai metropolitan region.

Many believe this ambition is not matched by action.

“The metro is not being built for how people would like to use it,” said urban activist Zoru Bhathena. “It is being built for the sake of it.”