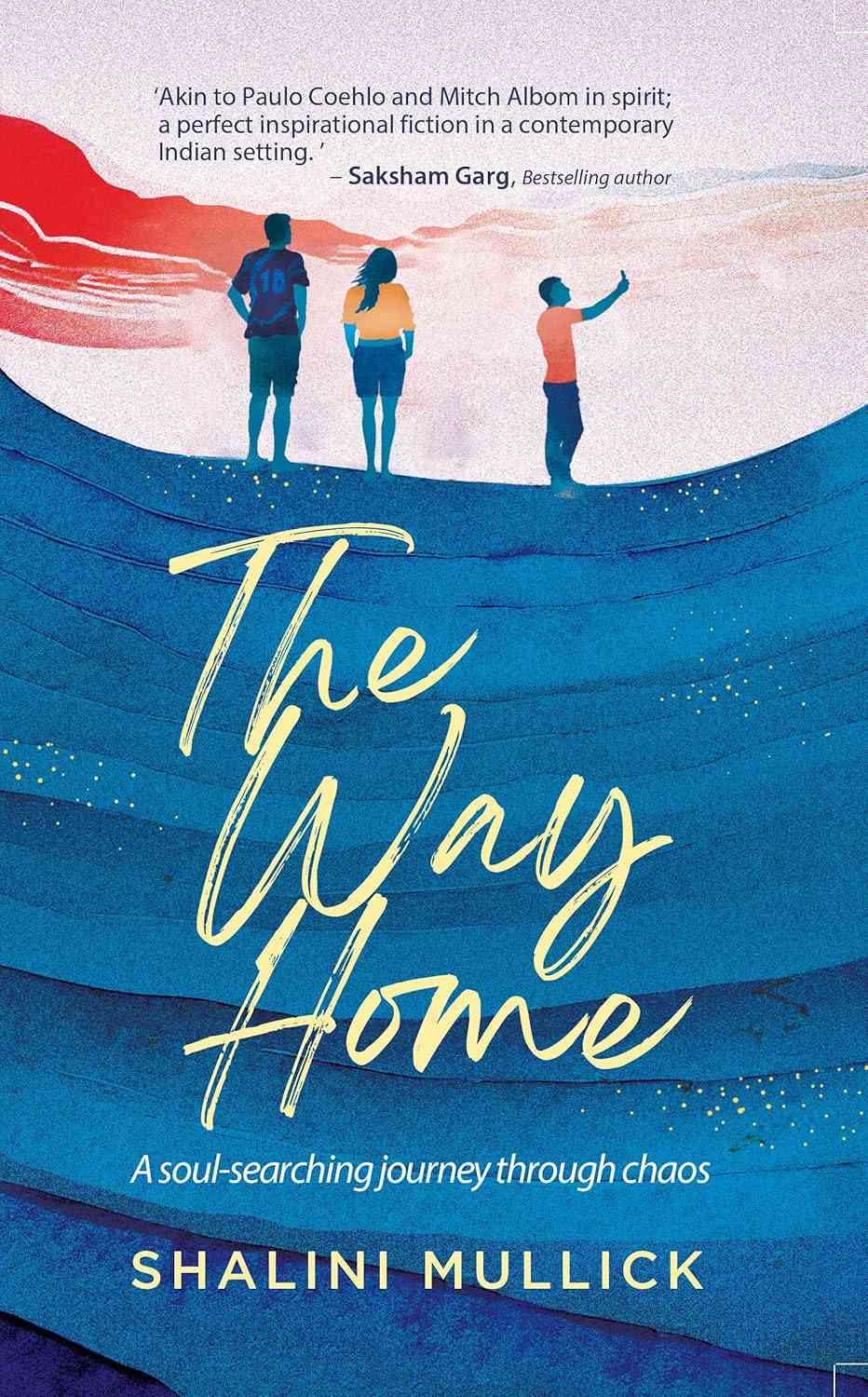

Anya is grieving the loss of her beloved sister and is desperately in denial. Neel is consumed by the shame of not living up to the accomplishments of his overachieving parents. Roys’s Impostor Syndrome and a crushing heartbreak have depleted his self-confidence, making him give up his career as a surgeon.

Seeking refuge from their inner demons, the three millennials flee to Goa, where they become friends. Will their friendship help the trio shed their demons and reclaim their life and happiness? Can this camaraderie give them the connection they need to embark on a journey of self-discovery and healing? Or is it too little, too late?

As the OR became abuzz with activity and the patient was wheeled in, Roy felt good to be in scrubs again. Maybe he could wear scrubs to work on days he didn’t have meetings, or at least get rid of those formal shoes that seemed to be designed for people who had had three toes amputated. Or he could offer to cover for the surgery team more often – something that he had avoided whenever Naik suggested it.

He made the incision and sliced through the layers of skin, fascia and muscle.

Anya’s eyes followed the scalpel, then his hands and his arms.

Anya saw how he was deeply focused. He seemed oblivious to the low, constant noise of people speaking, equipment whirring, and monitors beeping. Just like Zoya, when she would be handling a complicated pregnancy. Or when Anya herself would be intubating a patient. This was the real Roy, doing what he really loved. She watched him use the suction to clear the cavity of the blood.

She couldn’t help it when her eyes rested on the part of his chest that remained exposed in the scrubs, the sinewy hair standing out in the golden yellow beam of light from the overhead operating lamp.

Anya, this is where I will need your help. Can you please hold this retractor for me? Firmly, but without too much pressure.”

She shifted her attention from the surgeon to the surgery.

His field of vision clear, Roy finally saw the spleen. It was turgid with blood. He identified the injury and the offending vessel which was oozing a few millilitres at a time. A grade 1 laceration. He quizzed the surgical resident who had joined them about the classification of splenic injuries. And he wondered if he had been wrong about his decision to remove the spleen. For a surgeon, humility and arrogance went hand in hand. If the blunt arrogance that nothing would go wrong was essential, so was the humility to recognise that they may need to revise and review their decisions. Fixing the bleed was possible, but it was a more complicated task. In an earlier life, he would have revised his plan immediately. Now, he vacillated, but just for a moment. The best possible thing for the patient was repair, not removal. And each patient deserved the best option.

He took a deep, long breath.

Anya watched as the trainee listened and observed in rapt attention. There was no doubt about it. Roy was a star in the OR. A surgeon was the leader of a huge interdisciplinary team, and Roy was a natural. What was he doing pushing files? Why was he wasting his life and throwing away a stellar career?

“I don’t think we need to do a splenectomy. I can fix the bleed.” Roy’s voice filled the OR. She could feel a stillness crop up around her – everyone was taking in Roy’s words. The team realised that this was a critical decision. One that was a test of both the skill and clinical judgement of the surgeon. Not every surgeon would be able to make the decision with so much confidence. But Roy’s self-assured stance dissolved any doubts they might have had.

“Repairing a splenic rupture is a tedious, more complex process. But where it is possible, we must try a conservative approach.” Roy addressed the surgical resident, who clearly hadn’t seen this coming. Roy answered the unasked question, “Yes, it is a judgment call. But then, everything in life is one, isn’t it? In surgery, as in life, you must have the spine to make difficult calls and follow them through.”

Again, Anya watched his hands. Deft, nimble, and precise. He sutured the bleed carefully. Then he double checked the repair and proceeded to close, while documenting the procedure on a voice note.

They filed out to the anteroom. The feeling after a surgery – when the cast returns from the stage to the wings – is also unique. The tension has dissipated, the guard can be lowered, and the coffee can be savoured. Sweet buns were passed around, and Anya took two.

Roy dictated the post-op instructions. he was hungry too, but he let the buns pass.. He looked at Anya. The high ponytail and frizzy, opinionated hair were finally out of the surgical cap and falling over her face. She was devouring the buns and had put her feet up on the single footstool in the room – as if she had been the lead surgeon and was exhausted af er a major surgery. He smiled. It had been good having her around.

“I need to get back to my office for some calls. Would you do me a favour and check on Tess later?” Roy asked Anya.

“Sure.”

Roy returned to his room and reached into his drawer for an energy bar.

Anya lingered on, waiting for the patient to be shifted to post-op. Being part of an Operating Team af er so many years had been exhilarating. And watching Roy operate had been like watching poetry in motion. In all the time they hung out together, he hardly spoke about his training and work in surgery, but it was obvious that he was very accomplished. She checked out Roy’s LinkedIn profile. A trauma surgeon with a fellowship in abdominal trauma, and one of the few Indian doctors to have received the “Silver Scalpel” award for upcoming surgeons. A very impressive profile indeed. She would never have known it from the single line introduction on the H-of-H app, which simply stated, “Roy is a surgeon and hospital manager.”

Like the ocean that he loved, Roy hid a lot beneath his surface. He had so many layers to him, and it felt as if she could never completely get to know him. Why did he keep his real self hidden even from his friends?

Excerpted with permission from The Way Home, Shalini Mullick, Readomania.