The simmering tensions from the 1947 Kashmir dispute and Pakistan’s territorial claims that the Rann of Kutch – a peninsular tract of land with an area roughly of 8,880 square miles surrounded by the Indus towards the west and the Gulf of Kutch in the south – was part of Sindh province, were straining the two countries’ relations and became a significant precursor to the 1965 war. Topographically, the Rann of Kutch is divided by a highland into two parts – the Great Rann in the north (6950 square miles) and the Little Rann in the south-east (1930 square miles). The former connects with the Arabian Sea through Kori Creek in the west, and the latter is connected with the Gulf of Kutch in the south-west. The eastern edge of the Kutch merges with the Luni drainage area. Described as a “bowl-shaped depression”, the north-eastern part of Kutch resembled, as the Imperial Gazetteer of India described, “… large tract of salt with dazzling whiteness … Except a stray bird, a herd of wild asses, antelope, or an occasional caravan, no sign of life breaks the desolate loneliness”.

Millennia ago, the Rann of Kutch was far from a desolate landscape. Archaeological and geological evidence reveals a thriving hub of life during the Harappan period, where settlements like Dholavira and Lothal flourished. The Rann of Kutch was indeed a bustling navigational channel, offering safe harbours for overseas trade and inland commerce along riverine routes that connected to the Sindh region. The lost Saraswati River mentioned in ancient Indian traditions, as some evidence suggests but continues to be debated, flowed independently into the Arabian Sea, possibly “along the courses of the now defunct rivers such as Ghaggar, Hakra and Nara” during the Harappan Bronze Age and the Iron Age Vedic period. What was once a fertile delta of the Indus and its tributaries was altered by tectonic disturbances, such as the one in 1819, which created a natural bund that stopped one of the branches of the Indus from flowing into the Great Rann.

Following the partition of the Indian subcontinent, the state of Kutch acceded to India, while the province of Sindh became a part of Pakistan. The boundary between the two, like many issues of that tumultuous time, became a point of contention and remained unmarked for years to come. Pakistan staked its claim to the Rann as a landlocked or an inland sea, and under international law, the boundary should, therefore, run through the middle. India argued that the Rann had never been classified as such, and pointed to a 1906 British administration note that declared both the wetness and dryness of the Rann as appearing to be a swamp or marshland. The British understanding was rooted in the observations employed by G Le G Jacob, who in 1844 wrote, “I do not know any English word exactly corresponding to Rann. It is neither exclusively a swamp, nor a fen, nor a desert, nor a salt marsh, but a compound of all.”

In further support of its claim, India referred to historical documents, referencing official maps spanning from 1872 to 1943, sources such as the Gazetteer of Sind from 1907, the Imperial Gazetteer of India published in 1908 and 1909, as well as documents from the political departments dated 1937, 1939 and 1942. These proved that the Rann of Kutch fell squarely within the Western State Agency that had become part of India as a result of accession. Pakistan, however, based its claim on the historical invasion of the Rann by the Sindh ruler Ghulam Shah Kalhora in 1762, asserting that this act established Sindh’s juridical boundaries, which Pakistan argued remained valid even after 1947. But India swiftly countered, pointing out that Kalhora’s son, Sarfraz Khan, had withdrawn those very troops in 1772, undermining the continuity of the claim. For India, the territory had been “defined” but never “demarcated”, and, therefore, no valid dispute existed. Yet, Pakistan clung to Kalhora’s invasion as the foundation of its argument and the rationale of its claim.

Sensing the strategic value of the Rann of Kutch, India, in the 1950s, took steps to fortify its position. It established a major naval base in the Gulf of Kutch, built an air base in Jamnagar (historically known as Nawanagar) and stationed an army garrison in Khavda, just south of the 24th parallel. India had secured a commanding foothold, from which joint military operations could be swiftly launched deep into Pakistan, driving a powerful wedge between northern and southern Sindh, severing Karachi from the rest of Pakistan and choking its access to vital sea routes.

In 1956, tensions over the Rann had erupted when Pakistan set up a post at Chhad Bet, prompting swift action from Indian forces, who moved in and overwhelmed the Pakistani presence. A ceasefire line was drawn in the Rann in 1958, and two years later, a ministerial-level meeting cautiously agreed to maintain the status quo until such time as the de jure boundary was finalised. Recognising the vulnerability of the border to Pakistani encroachments, the 7 Grenadiers camel battalion was reorganised into an infantry unit and positioned around the line of control between Bhuj and Khavda. The Bhuj airstrip was upgraded to accommodate fighter aircrafts, while all-weather airstrips were constructed at Chhad Bet, Khavda and Kotda, enabling Austers and Dakotas to land with ease. A saltwater distillation plant was set up at Chhad Bet, and a protective bund was built to guard against tidal flooding in the area. As a long-term measure, several roads of strategic importance were proposed to be built. With these measures in place, India fortified the region, ready for any future threats.

Public opinion in Pakistan could never forget Indian antagonism, and the Rann remained a critical piece in Pakistan’s ambitions, waiting for the right moment to be played. As mentioned earlier, in 1963, Pakistan’s foreign minister Bhutto went to Peking eager to break bread with the Chinese communists. As an ideological state, the allure of forging ties with fellow ideological nations such as China was irresistible, but more importantly, it could provide a counterweight to a bigger and stronger India. Pakistan was more than willing to bend backwards, and apart from the boundary agreement and cultural cooperation, it also became the first non-communist country to start its commercial flights to Beijing. Years later, in his final testament, Bhutto regarded his efforts in forging ties with China, despite US pressures, as the crowning achievement of his legacy. On a visit to the US in November 1963, just before the state visit of the Chinese leader Zhou Enlai to Pakistan, Bhutto met with President Lyndon Johnson and received a veiled warning: “He [Johnson] wanted Bhutto to know there would be a serious public relations problem here if Pakistan should build up its relations with the Communist Chinese. He [Johnson] was not pro-Pakistani or pro-Indian but pro-Free World. Such a state visit would make it increasingly difficult for us.”

The Sino–Pakistan bond has proven to be vital to Pakistan’s social and economic development, especially in the hydropower and roadway sectors. China, though, in the early phase, maintained a discreet stance in its relationship with Pakistan, even opting to remain uninvolved in the India–Pakistan wars of 1965 and 1971; but by the mid-2000s, it began to elevate Pakistan as a crucial ally in its global ambitions, driven in part by shifting dynamics in US–India relations. Notwithstanding concerns over debt and security – dismissed by China as Western propaganda – the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has, to date, delivered $25.4 billion in direct investment, created 2,36,000 jobs, built 510 km of roadways and generated more than 8000 MW of electricity.

By January–February 1965, the Rann had become a volatile flashpoint. In fact, trouble had already started in the Kanjarkote area several months earlier, with Pakistani forces frequently trespassing into Indian territory. Kanjarkote was a fort in ruins, about 1.3 km south of the Pakistan border on the northwestern fringe of the Rann. While the area south of Kanjarkote was a flat and featureless plain, the north consisted of a series of parallel sand dunes providing a vantage point for Pakistan troops. Pakistan had developed its border area around Kanjarkote with a sizeable town called Badin, 30 km from the border, complete with drinking water, road connectivity, communication and an airfield nearby with radar. In contrast, no drinking water was available for Indian troops except at Khavda, and a very limited water provision at Vigokot, which were 104 km and 119 km from the border, respectively. The logistical advantage prompted Pakistan to deploy its Indus Rangers into Kanjarkote, a move that India claimed violated the 1958 ceasefire line agreement. Pakistan, however, believed India had deliberately provoked the situation, using the spectre of external aggression to divert attention from its own internal crises. Rather, Pakistan saw India’s internal disturbances as an opportune moment to test and challenge its neighbour.

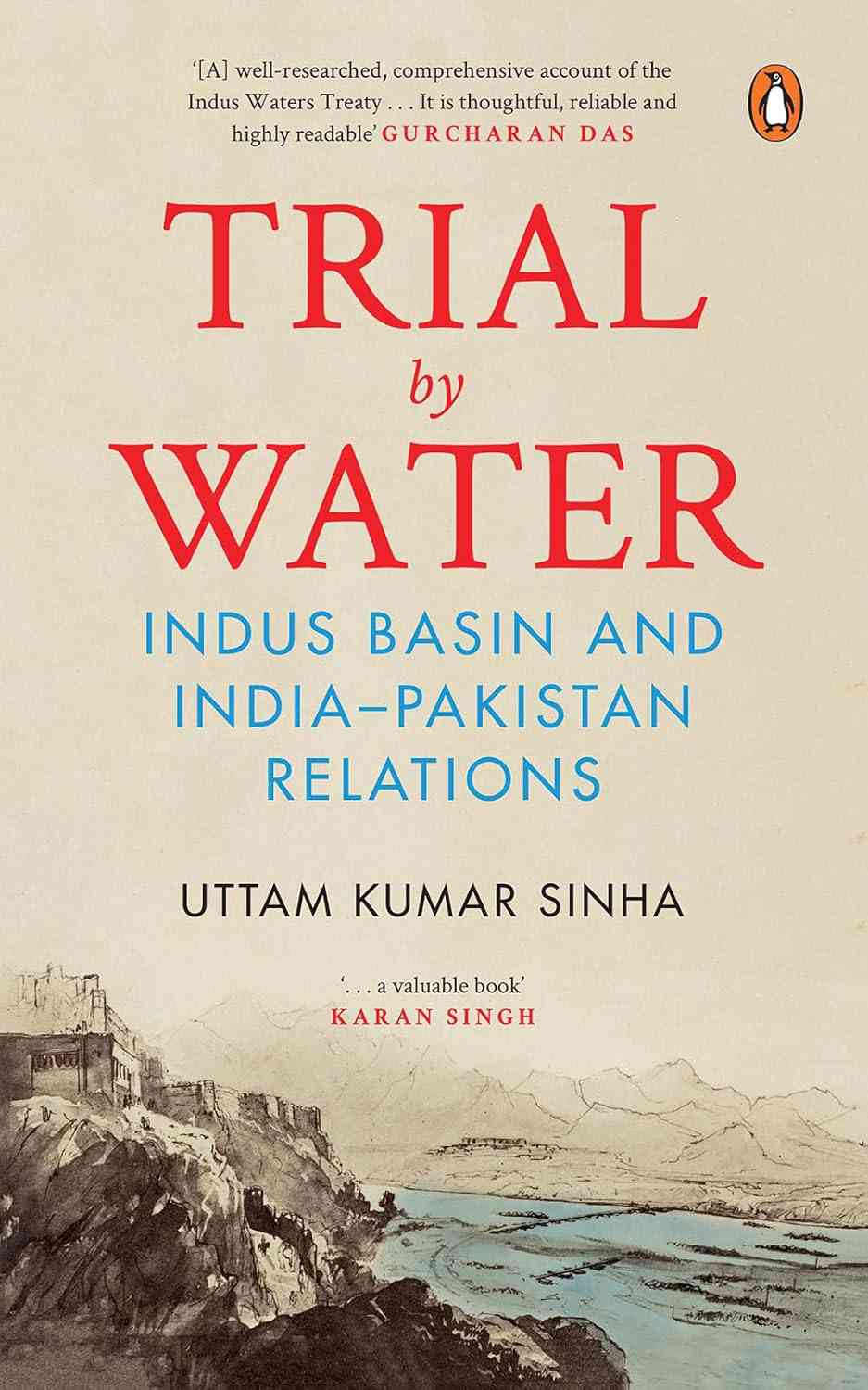

Excerpted with permission from Trial by Water: Indus Basin and India-Pakistan Relations, Uttam Kumar Sinha, Penguin India.