An assassination is the murder of a public figure. It usually refers to the killing of a head of state or other prominent person for political motives. The reasons behind the killing could be to undermine a government, grab power, take revenge, get attention for a cause, or start a revolution.

The person who carries out an assassination is called an assassin. You may have played the action-adventure video game Assassin’s Creed. Or watched the film based on it. But have you ever wondered where the word “assassin” comes from?

The word assassin is possibly derived from the Arabic word hashshashin, which was used to refer to a religious sect of Ismaili Shi’a Muslims of the Nizari lineage that originated in Persia in the eleventh century ce. Its original leader was Hassan al-Sabbah, a missionary from Egypt. He ran his secret society of Hashshashins or Assassins from his stronghold in Alamut in northern Persia. At its peak the community extended to Egypt, Syria, Yemen, southern Iraq, southwest Iran and Afghanistan.

The Assassins would defeat their enemies not with a large army but by deploying individuals who would infiltrate enemy strongholds and use subterfuge to kill key military and political leaders. They were masters of disguise and usually used knives to carry out the killings. The Assassins employed their techniques against their rivals in the Muslim world as well as European Crusaders. The latter were Christians who fought in the Middle Ages to win the Holy Lands from Muslims.

The word “hashshashin” means “consumer of hashish”. Hashish is a drug derived from the cannabis plant. Enemies of the Assassins may have attributed their ability to strike at their opponents so effectively – as well as their willingness to die for the cause – to the use of hashish. Or it may simply have been a derogatory term applied to them without any basis in actual drug use. In other words, it may have been like calling someone a pothead in order to demean them. Later, the word hashshashin lost its original connection to drugs and started being used in the sense of “outlaw”. And in Egypt in the 1930s, it was used to mean “noisy” or “riotous”.

The Venetian merchant and traveller Marco Polo wrote about the Assassins. He mentioned that the young boys who were being trained as assassins were given intoxicants and taken to a secret paradisical garden by the leaders of the sect. The boys were given this experience of paradise as a taste of things to come in the afterlife if they successfully carried out their missions.

There is another school of thought that the derivation of assassin has nothing to do with hashish but simply means a follower of Hassan. As noted earlier, the first leader of the Assassins was Hassan al-Sabbah. According to texts from Alamut, Hassan called his disciples “Assassiyun”, meaning people faithful to the “Assass” – the “foundation” of the faith. “Assassin” may actually have come from “Assassiyun”.

The Assassins finally met their match when they tried to assassinate the Mongol leader Möngke Khan, grandson of Gengis Khan. The Mongols went after them and defeated them in 1256 in Alamut. Though the Assassins managed to retake Alamut, they lost it again. With most of their strongholds gone, they operated independently for another century as contract killers. But they disappeared eventually.

The Crusaders brought home to Europe stories about the militant Ismaili sect within the Nizaris, and their nickname Hashshashin entered European languages. The word became assassini in Italian and entered English as “assassin” in the 1530s. By that time, the original meaning of the word was long forgotten. The generalisation of the sect’s nickname to mean an assassin in the modern sense had already happened in Italian in the early fourteenth century.

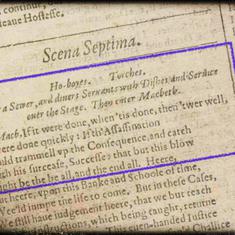

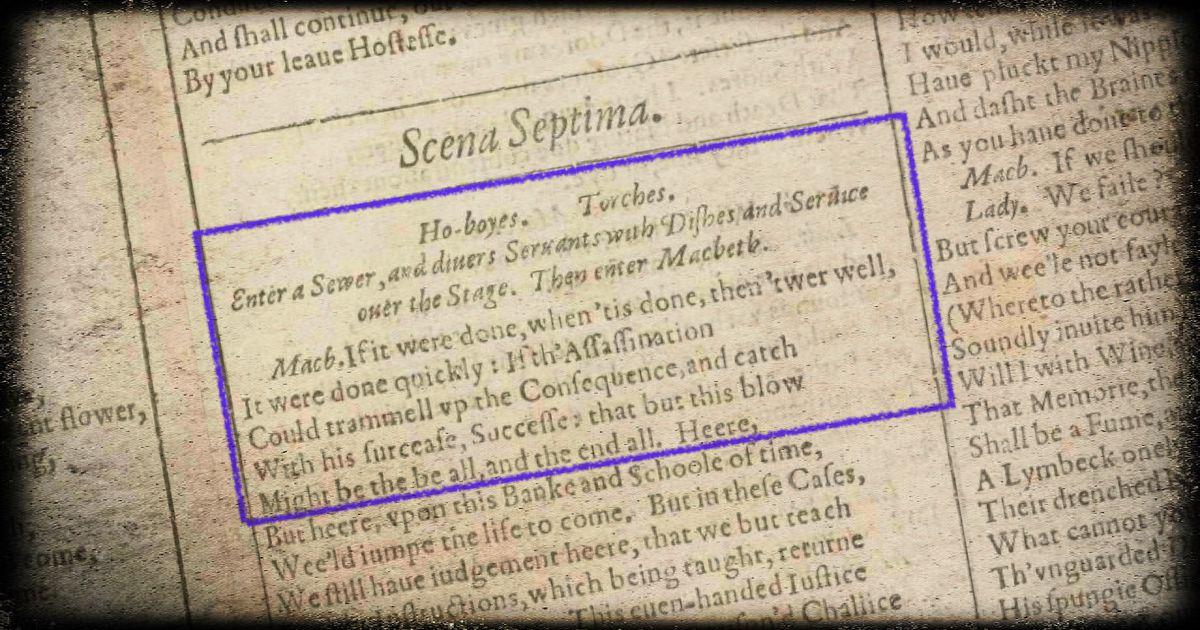

The verb “assassinate” was first recorded in English in 1600 in a pamphlet by Matthew Sutcliffe titled A Briefe Replie to a Certaine Odious and Slanderous Libel, Lately Published by a Seditious Jesuite. The noun “assassination” appeared sometime later in Act 1, Scene 7 of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which was first printed in 1603:

If it were done when ‘tis done, then ‘twere well

It were done quickly: if the assassination

Could trammel up the consequence, and catch

With his surcease success; that but this blow

Might be the be-all and the end-all here,

But here, upon this bank and shoal of time,

We’d jump the life to come.

Assassinations have been used as a tool of power politics throughout recorded history. The first known victim of an assassination is said to be the Egyptian pharaoh Teti. This assassination would have taken place c. 2333 BCE.

Chanakya wrote about assassinations in Arthashastra, his famous political treatise. His student Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Maurya dynasty in India, used assassinations to eliminate some of his enemies. In his book The Art of War, the Chinese general Sun Tzu too wrote about assassinations as an effective political tool. Two millennia later, Italian diplomat Machiavelli wrote in his book The Prince that it was advisable to assassinate enemies whenever possible so that they couldn’t trouble you anymore.

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Austria in 1914 precipitated World War I. The assassin was a Serbian nationalist called Gavrilo Princip. Closer to home, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948. His assassin was Nathuram Godse. Prime ministers Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi were also assassinated in 1984 and 1991, respectively.

You don’t always have to be a political leader for your murder to be considered an assassination. In 2006, investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya – a critic of Vladimir Putin – was shot and killed in Moscow. She is one of the many journalists who have been assassinated during the Putin regime. Maurizio Gucci, the one-time head of the Gucci fashion house, was assassinated in 1995. Investigations revealed that the murder was carried out at his former wife’s behest.

So, from a word meaning “hashish-eater”, which was applied as a term of abuse for a sect in medieval Persia and Syria, we get the English word assassin, meaning “a murderer of public figures”.

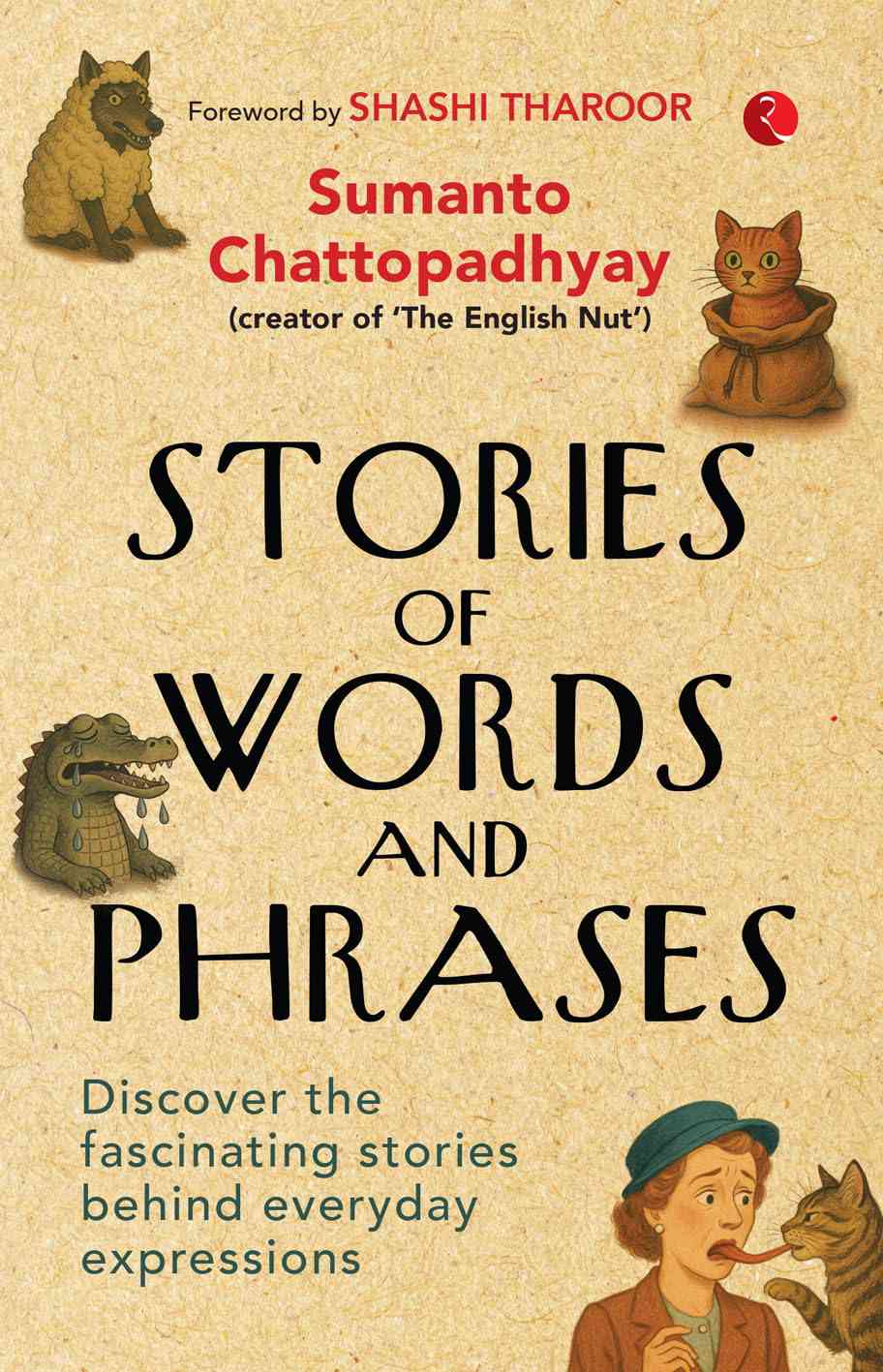

Excerpted with permission from Stories of Words and Phrases: Discover the Fascinating Stories Behind Everyday Expressions, Sumanto Chattopadhyay, Rupa Publications.