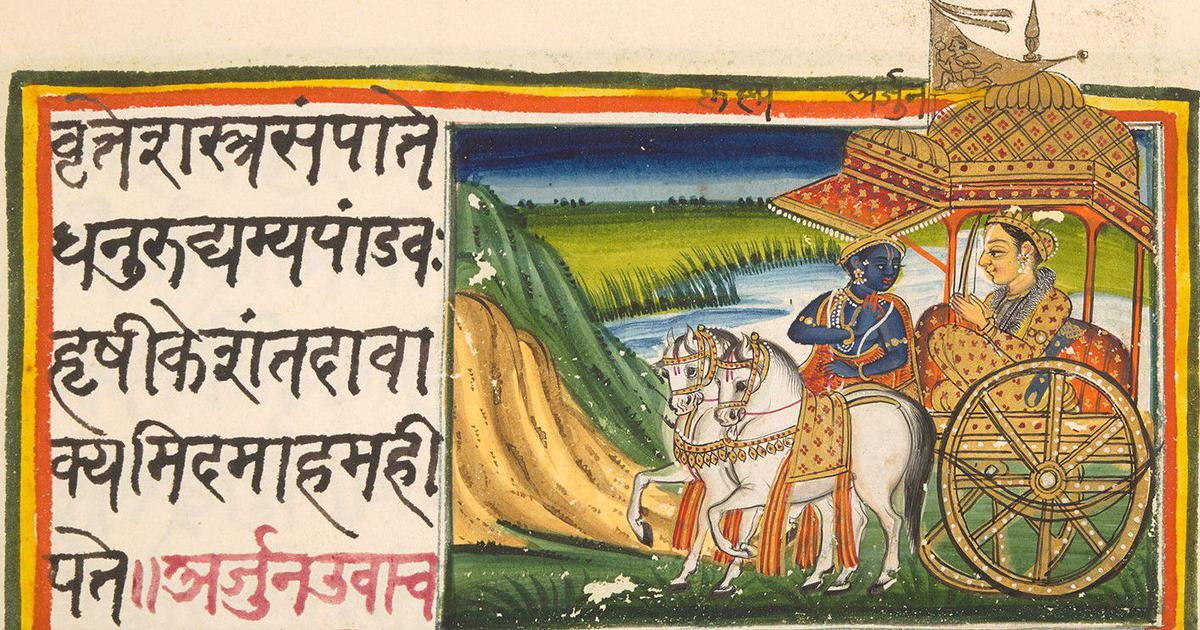

By understanding the Self (Atman) as superior to the intellect (ego) and using this intelligence to make the mind steady, O mighty-armed one, you can vanquish the enemy in the form of selfish desire, which is difficult to subdue.

— Chapter 3, Verse 43

The doctrine of karma is central to Vedic philosophy and for that matter to all the Indic religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. Simply put, karma is the belief that every action automatically generates a corresponding result: “As you sow, so shall you reap.” Karma is not a consequence administered by an external judge. Instead, it applies the natural logic of cause and effect that we observe in all our activities. You water a plant diligently; it grows. You forget to do so; it withers.

Meritorious actions yield positive outcomes, whereas unworthy behaviour inevitably leads to suffering. Whether bitter or sweet, these fruits must be tasted in the current life or a future one to come, but they are inescapable. Today is the result of yesterday and tomorrow will be the consequence of today. Vedanta teaches that as long as karma is accrued, either positive or negative, rebirth over and over in a perpetual cycle is unavoidable. Karmic repercussions, pleasant or painful, compel one to return to the mortal realm. Therefore, Swami Vivekananda described karma as binding, whether in chains of gold or of iron. Of course, this does not imply that we should abandon virtuous action. The transition from bad karma to good karma is necessary before finally going beyond karma.

Ultimately, life’s goal should be to exhaust accumulated karma without creating additional karmic baggage. Building punya, or spiritual wealth, is the best use of our human birth, as the true goal of life is moksha, liberation. The world offers the opportunity to learn; thus the human body serves as an ideal vehicle to liberate oneself from the cycle of rebirth. The Gita emphasises that the precious opportunity of being born as an advanced life form is not squandered if spiritual wisdom is made one’s highest purpose.

Death does not wipe the slate clean. Instead, you reincarnate, bearing the burden of your previous karma, with each birth providing an opportunity to make redeeming behavioural changes. After all, we come with nothing but karma, and it is all we take with us when we die. Over multiple lifetimes, we each accumulate a considerable karmic load, referred to as sanchita karma. After a temporary interval in heaven or hell, when the subtle body, the soul, is forced to reincarnate in a physical form again, specific karmas are chosen to be experienced in the upcoming lifetime. These karmas manifest as unexpected misfortunes or sudden windfalls, known as prarabhda karma, or karma already set in motion like an arrow launched on a fixed trajectory. We are born with prarabhda karma. These experiences must come to pass, as facing the consequences of previous deeds is unavoidable. Therefore, chance happenings are not random events but incidents that can be attributed to prior actions.

However, having a karmic destiny does not mean we are puppets on a string with no free will. Destiny is not chance but the result of conscious choices made. The purpose of karma is educational, not punitive. Therefore, rather than cursing one’s bad karma, one should view it as a means to self-improvement. Within the karma we face lies the opportunity for liberation based on how we handle preordained situations. Think of prarabhda karma as lessons we have chosen to provide teachable moments in our current lifetime. Since we are bound by prior actions, we cannot prevent events that are destined to happen (nibaddah svena karmana). However, we have full authority in how we approach predestined situations, just as we have complete control over studying a preset curriculum in school. Once you learn the lesson, the karmic debt is absolved. You graduate!

Life is essentially a series of diverse experiences. Our perception of circumstances and our response to challenges shape our future karma, as individuals react differently to the same problem based on their level of spiritual advancement. Therefore, recognising that our actions have far-reaching consequences, righteous conduct becomes paramount and must be properly understood (4.16–17). Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. Although an inner voice guides us in discerning right from wrong, we often choose to ignore it. A striking illustration of this shortcoming is found in the Pandava Gita, an anthology of verses attributed to various characters from the Mahabharata. Duryodhana articulates an all-too-common human failing with surprising honesty. When Krishna, in his role as a mediator, tells Duryodhana he is being unfair by usurping the property of his cousins, he retorts, “I understand dharma (righteousness), but I am not inclined to follow it. I also know what I am doing is adharma (unrighteous), but I cannot stop myself from it.” We are all like Duryodhana at times.

In the Gita, when Arjuna asks, “What is it that impels us into unrighteous action despite knowing better?” Krishna traces the origin of wrongdoing to selfish desire. When kama overpowers the mind, forcing it to surrender to sense pleasures, even a person of superior intelligence is dragged down the slippery slope of destruction (indriyani pramathini haranti prasabham manah. In Chapter 2, Verses 62 and 63, Krishna masterfully lays out how easy it is to be led astray if one allows oneself to succumb to worldly temptations.

Giving in to compulsions triggers unrighteous conduct. Feelings of raga – intense attraction, and dvesha – extreme repulsion, cause us to abandon reason and act recklessly. Once these two tyrannical masters establish their lordship, they appropriate the mind, making it a slave to their demands. It is nearly impossible to ignore a strong desire, even with considerable willpower, once it takes a firm hold. Consequently, judicious conduct is only possible by keeping overwhelming likes and dislikes in check.

Although the power of judgement is available to all of us, exercising intellectual discernment is a matter of choice. When a passion ignites like a fire in the mind, there is a narrow window of opportunity to snuff it out before it becomes an irrepressible inferno. On the other hand, if the brakes of self-control are not applied at the appropriate time, yearning takes on gigantic proportions like the force of a mighty current, making it nearly impossible to prevent oneself from being swept away. Hence, relying solely on how we feel for direction is foolhardy. Cultivating a rational mind that is not led by emotional extremes is essential to replace the impulsiveness of going with the heart alone with careful consideration. The adage ‘sleep on it’ is not without merit; it prevents acting impetuously when driven by passion.

The Gita empowers us with the awareness to make the right choices in our actions. Krishna systematically outlines the eight-step trajectory to moral bankruptcy stemming from the compulsivity of raga-dvesha.

It begins with constantly thinking about a specific desire or aversion – dhyayathah.

A thought that continuously lingers in the mind takes hold as an obsession, forming a deep attachment – sanga.

From the passion thereby ignited comes a hankering to fulfil the desire – kama.

If the desire is fulfilled, it results in greed for more – lobha. And if the desire is not satisfied, its obstruction results in anger – krodha.

Both greed and anger cause a state of mental delusion – sammoha.

In a state of delusion, the sense of right and wrong becomes clouded – smriti vibhrama.

When the mind is hijacked by passion, judgment fails – buddhi nasa.

When the power of reason is destroyed, we stop thinking coherently. So we say and do things we would normally not do – pranasyati.

We are only too familiar with this predicament in our current times. Every day, we are bombarded with enticing advertisements aimed at increasing sales by kindling a burning desire for a product. When you repeatedly see a shiny luxury car on TV, you grow attached to the lifestyle it denotes. In a short while, this attachment progresses to picturing yourself enjoying the happiness it promises. You begin to feel a gaping void in your life, and the craving to own the car overwhelms you to the point that it becomes essential for your mental well-being. Obsession leads to anger if the object is beyond reach, but the desire does not diminish. Instead, it often finds ways to remove impediments that prevent you from attaining your desired goals. These means may not be righteous or prudent, but the inner voice is easily ignored as the craze intensifies and right and wrong become irrelevant. For example, a person may begin to steal from their employer or take a loan they cannot repay to buy their dream car, be prosecuted, and end up ruined.

Not just actions, our thinking also determines our karma. We do not realise the potency of our thoughts. Reflections affect every cell in the body, defining the frequency at which we function. The Gita says that we literally become our thoughts! Our beliefs mould our disposition. Like a magnet, the mind draws towards itself what it incessantly thinks about, so whatever you are preoccupied with becomes a reality. Since thoughts are vibrations that resonate in your life, an optimistic view attracts positivity, while a negative outlook invites negativity. To improve your lot, you must first alter your perspective.

Excerpted with permission from Life Is a Battlefield: Insights from the Eternal Wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita, Priya Arora, Penguin India.