In 1990, when Japanese manga artist Akeru Barros Pereira visited her husband’s ancestral village of Cansaulim in Goa, she was captivated by everything she saw.

“I’d walk around the quiet village with my baby on my back,” she said “I had a camera and was fascinated by the village scenes – especially the houses around.”

She was so charmed by stately Goan houses, she took pictures of them even as the family drove to the airport to return to Japan.

A few years later, when their children had finished high school, her husband, Joao Barros Pereira, a university professor in Kyoto, encouraged her to start drawing again.

In the 1970s and ’80s, as an undergraduate at Nara University, Barros Pereira had drawn 13 books of manga – the distinctive Japanese style of comics and graphic novels. She had published them under the pen name Toto Akeru.

She had stopped when their first child was born. But now, with more time on her hands, Akeru Barros Pereira decided to get going again.

“I remembered those pictures taken all those years ago, and based on those pictures, I began drawing Goan houses,” she said.

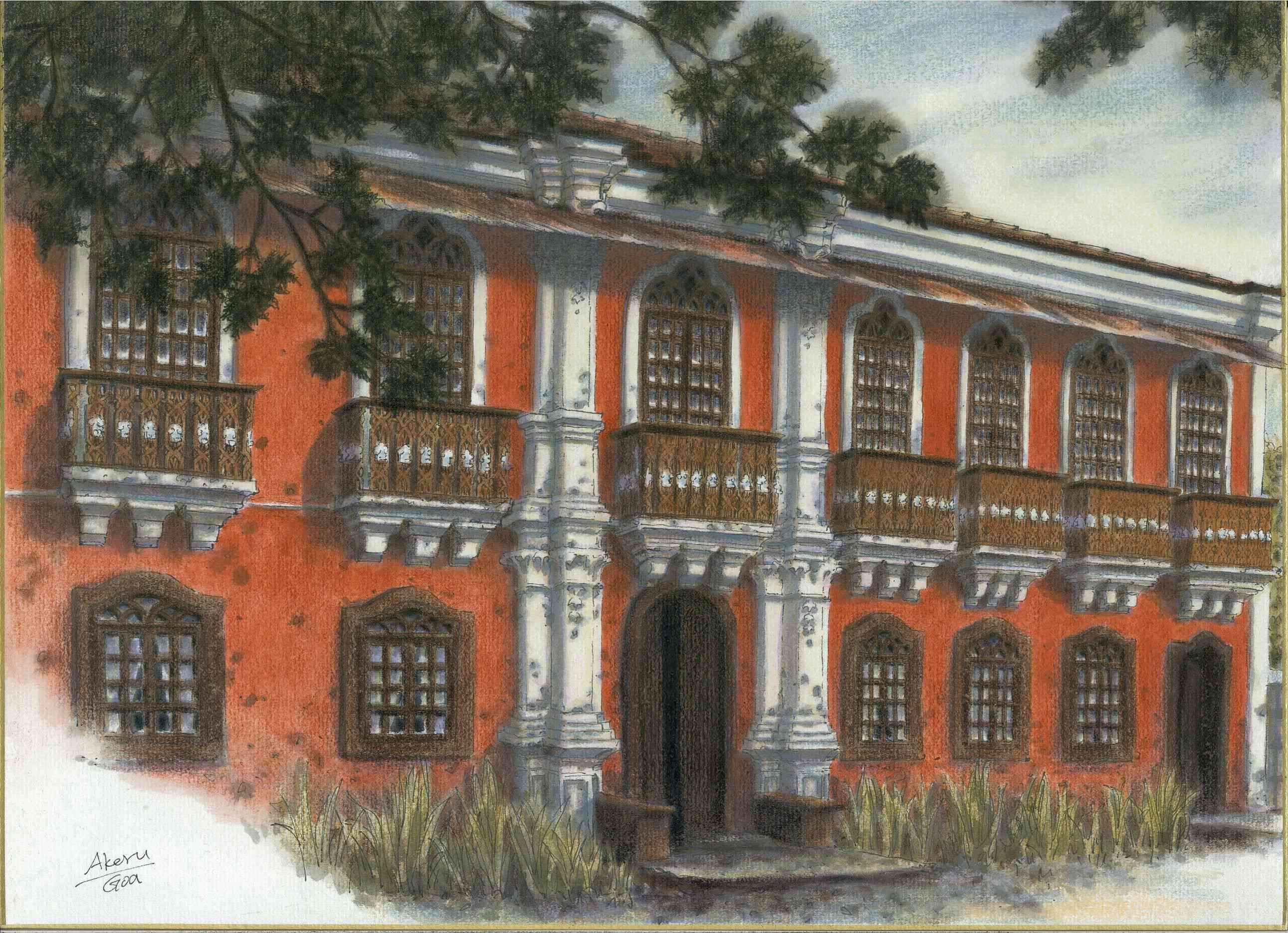

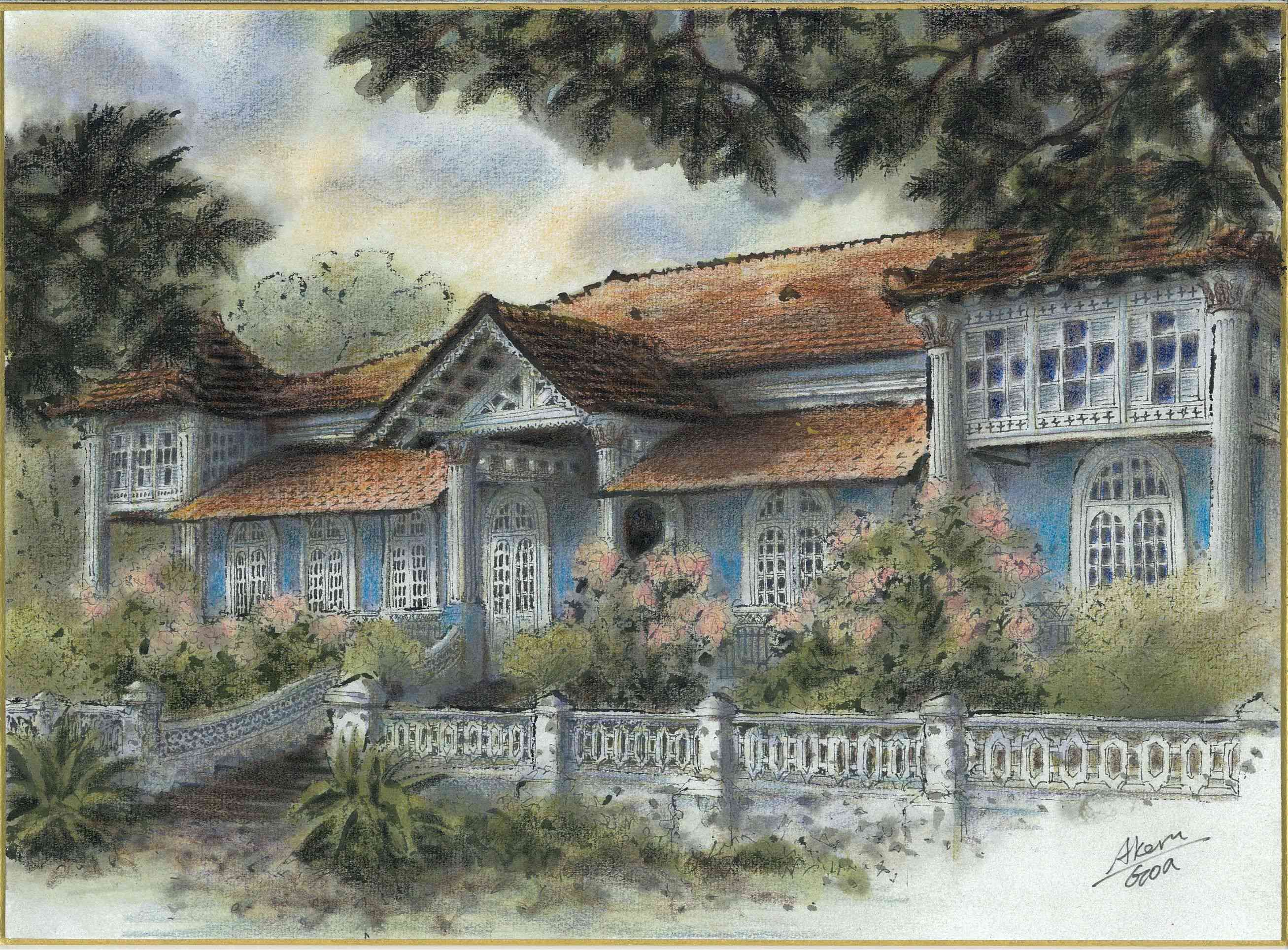

Using colour pencils, water colours and fountain pen, sitting in an apartment in Kyoto, Barros Pereira began to make her drawings on Japanese paper.

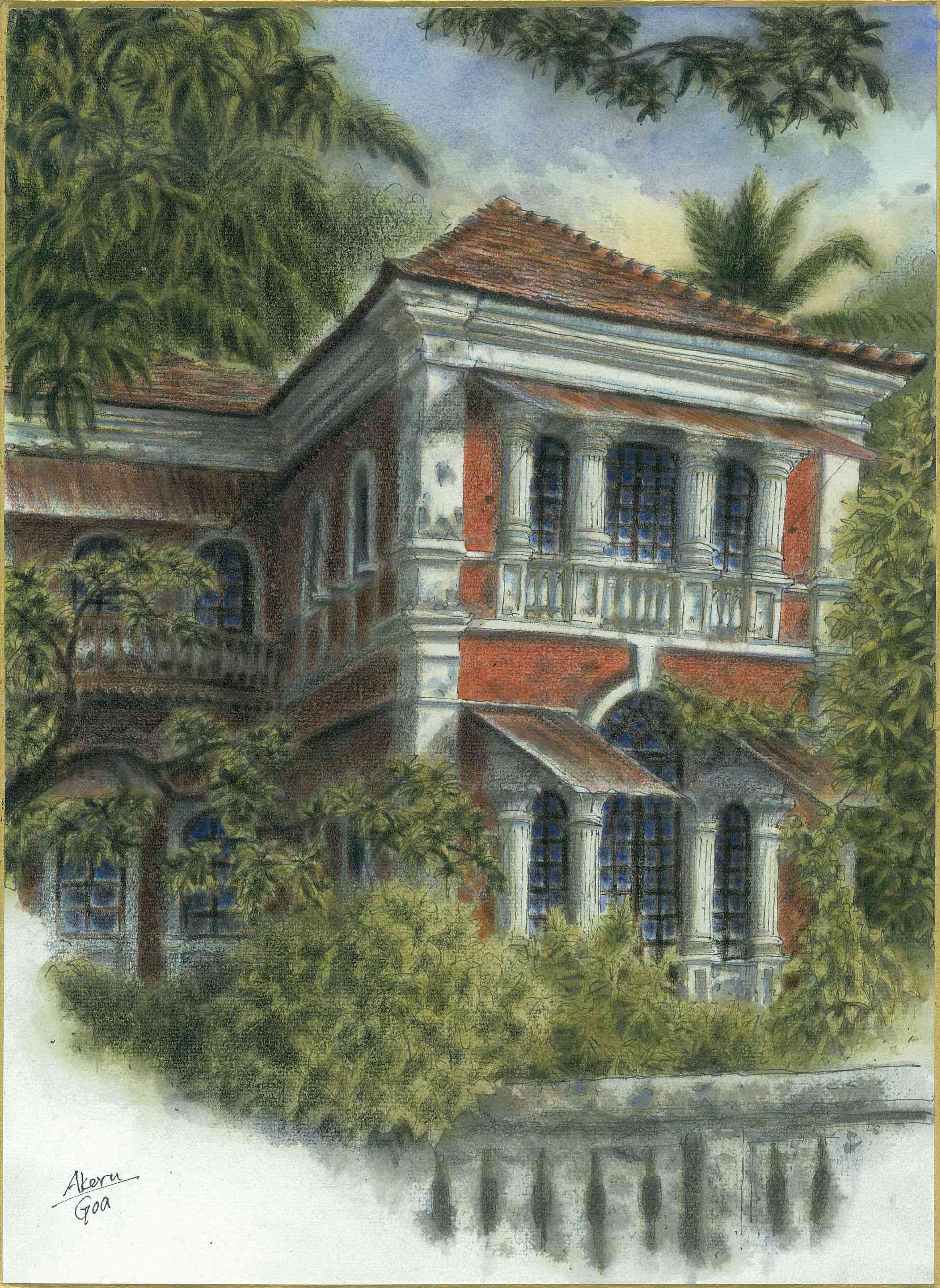

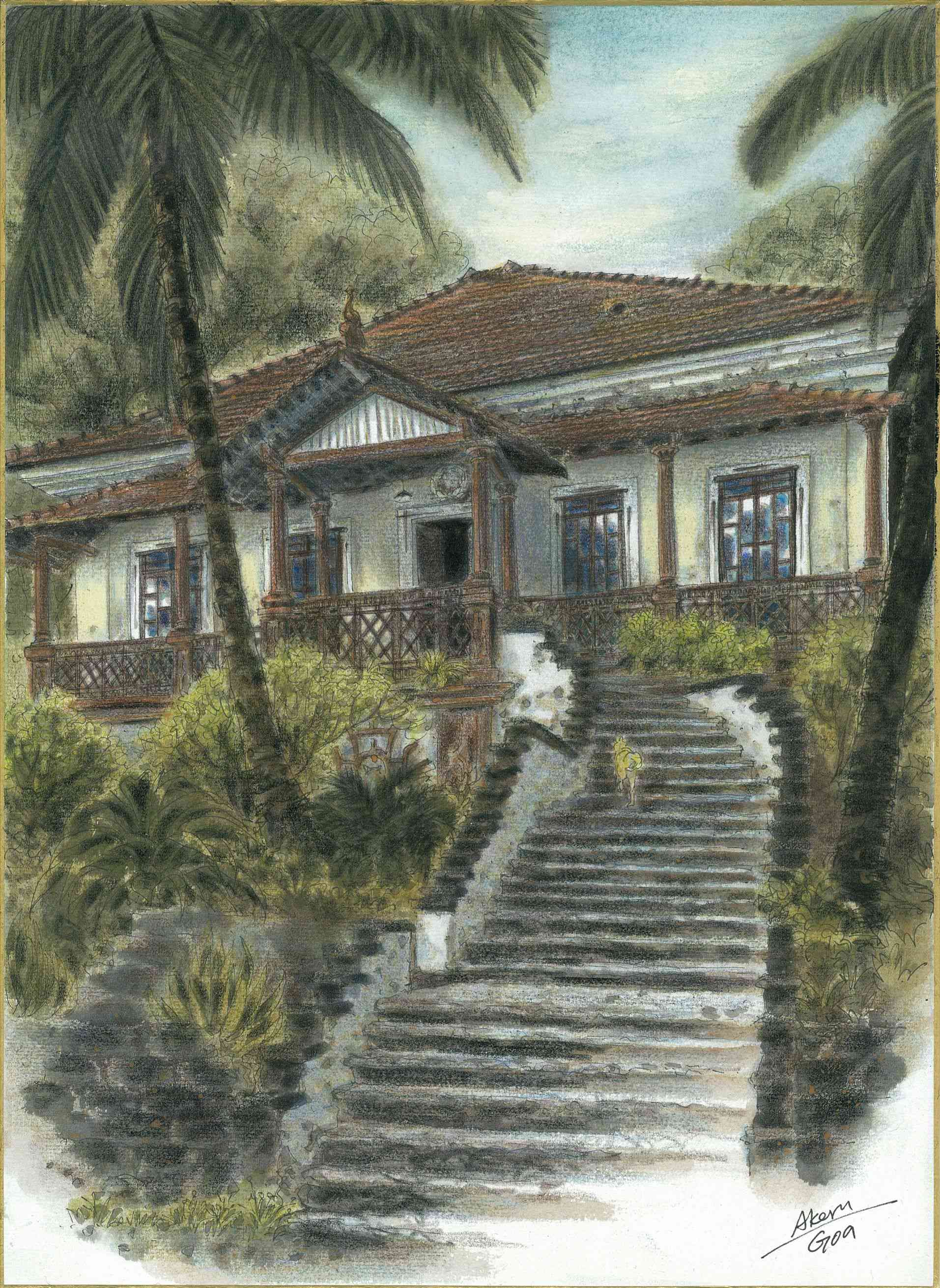

In her work, she recreated all the graceful elements of the Goan house – the elegance of cornices and pilasters, plinths and pediments, ornate stucco work, arched doorways, sloping red-tiled roofs, finials, balcaos, decorative gate posts, oyster shell windows, eaves boards, corbels and wrought iron railings.

The contrast between the homes in Japan and Goa could not be more striking, the artist said.

Rural homes in earthquake-prone Japan are built of wood and paper screens, while the apartment blocks in space-starved Japanese cities are compact. They are quite different from the stone and lime plaster structures of Goa.

Her pictures are enveloped with coconut trees and dense foliage. They attest to her fascination with Goan flora and give her works an ethereal, mysterious air.

The drawings were so atmospheric, architect Gerard da Cunha decided to publish them as a book in 2013. The Indo-Portuguese House, with text by da Cunha, features 50 of Barros Pereira’s works.

“The Indo-Portuguese house is the richest legacy of Goan society,” the book declares. “It is the result of European rule and all its cultural influences melding with its Indian subjects and their sensibilities, creating an extraordinary house. A house which is neither Western nor Indian, but having the attributes of a well-developed style, as rich and independent as any in this world.”

Da Cunha’s professional association with Barros Pereira predates the book. In 2008, he bought some of her drawings at an exhibition at the Kala Academy in Panjim to display in his highly regarded Houses of Goa Museum in village of Torda.

In the preface to the book, da Cunha explains why he admires Barros Pereira’s work.

“Here was somebody who really understood the nuances of the Indo-Portuguese house and could capture its many forms,” he writes. “…Akeru’s paintings of the Goan house have been taking up an important corner of my Museum for the last five years and it has helped explain this wonderful house in a way I never could. It has also brought great pleasure and understanding to all who visit.”

What makes her work so remarkable? Perhaps it is because she has the keener eye of the outside observer?

Sitting in the airy, light-filled antique drawing room of the Barros Pereira mansion in Cansaulim, with an array of French windows opening onto a wrap-around verandah, it is easy to understand Barros Pereira’s enchantment with the architectural style.

All around are similar manors, all equally grand, all seeped in centuries of family histories in rural Cansaulim.

Barros Pereira, who studied mathematics and philosophy, is a self-taught artist. Publishing manga at university honed her skills, she said, though those comics used only pen and ink.

The 1970s and ’80s were considered the Golden Age of manga, with dozens of magazines being published in a range of genres, aimed at a variety of demographics.

“In every elementary, junior high school, there’d be one or two manga writers or anime style artists,” Barros Pereira said. “Everybody wanted to become a manga writer…”

Her own fantasy genre manga novels were set in a fictional country, definitely Eastern. “I wanted to introduce Japanese young women and girls to countries other than Europe and the US, which held steady appeal at that time,” Barros Pereira said.

Since she began drawing Goan houses around 2005, she almost never created her work in Goa. Two- or three-week annual vacations to the state after a 24-hour journey there made it too hectic for anything more than site visits, she said. Instead, she would take lots of photographs and begin work when she was back in Kyoto, as time permitted.

Her work is lent some of its uniqueness from the ultra-thin Japanese paper she uses: it crumbles when wet and is usually mounted on board or cloth or ready purchased as pre-mounted shikishi boards.

There are many varieties of Japanese calligraphy paper, each of which gives the work a different effect, she said.

“Japanese calligraphy paper works amazingly well with colour pencils,” Barros Pereira said. She says it adds a soft tone to the colouring that gives it the stand-out effect that characterises her work.

She has experimented with pens, using a fountain pen earlier, and more recently switching to a calligraphy pen that does not fade as easily.

Over the years, Barros Pereira has drawn more than 200 Goan houses.

But she avoids drawing derelict houses, or ruins – preferring to present houses as they are meant to be, renovating them in her paintings, even if the structures she has shot require a little maintenance.

“These houses are living entities, heaving with the family histories and dramas of generations past,” said Barros Pereira. “I like to capture the hope and promise that they will live on, with new generations.”

Pamela D’Mello is an independent journalist, writer and researcher based in Goa.