In the cramped and dark Secret Annexe, where Anne Frank and seven others were hiding from the Nazis, Anne wrote in her diary about a night filled with fear as planes flew overhead and bombs exploded nearby. Despite the constant danger, Anne found comfort in writing. She poured her feelings, fears, and hopes into her diary – using storytelling to express what it was like to grow up in such difficult times. Her writings were later compiled by her father, Otto Frank, and published as The Diary of a Young Girl.

A new vocabulary

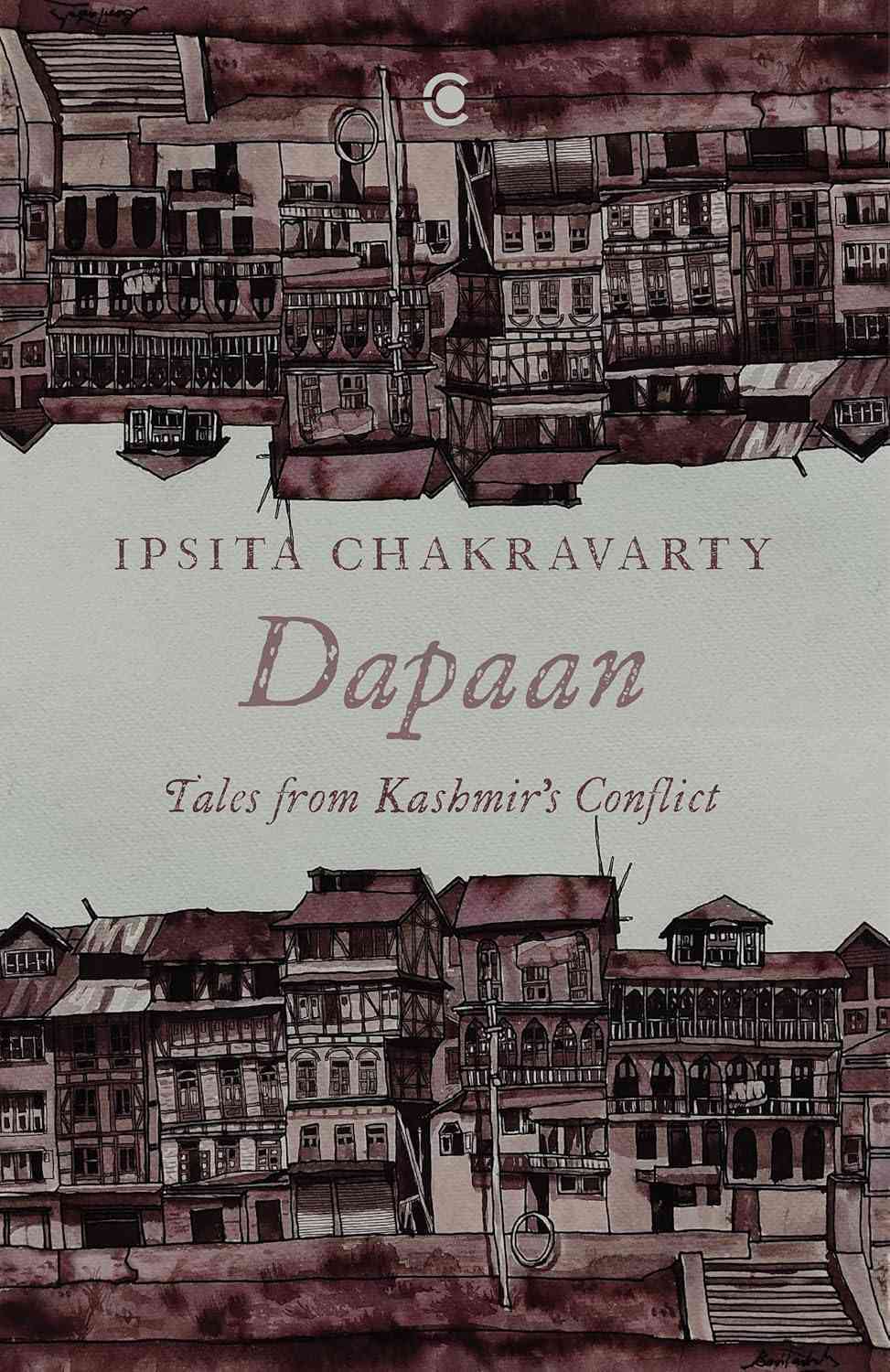

In Dapaan: Tales from Kashmir’s Conflict, a Dastangoh (storyteller) narrates a similar tale while recounting Kashmir’s descent into the turmoil of the 1990s. Written by journalist Ipsita Chakravarty, a former editor with Scroll, this haunting and probing work draws on interviews with ordinary Kashmiris, recounting stories of war within their homes and communities. Through folk tales and local idioms, Chakravarty explores how Kashmiris have developed a new language in response to the monstrous conflict that has deeply permeated their social sphere.

Dapaan – translation: it is said – is a Kashmiri word that has long been used to describe an event, a happening, or even a rumour. However, the term gained a more pronounced presence in the Kashmiri narrative public after the outbreak of the popular insurgency in 1989, becoming a way to describe militancy, militarisation, crackdowns, and curfews. It marked the beginning of a new vocabulary that entered public life alongside the rise of militancy.

When conditions – or the halaat – worsened, searches became frequent and intrusive, and Kashmiri homes lost the privacy they once had. People had to bury anything that might appear suspicious and land them in trouble. Chakravarty writes, “In houses across Kashmir, families were sorting through their things. Photographs of sons who had crossed over for arms training. Those had to be buried underground. Family photos of picnics and weddings where the sons were part of the group. Those had to go too, so that when the search parties came, they could pretend the sons did not exist, had never existed. What else, jokes, romances, tall tales told on winter nights”.

Kashmir’s halaat after 1989 became synonymous with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, as mass state surveillance and the regimentation of people and behaviour within society nearly obliterated the social sphere and annihilated solidarity. In this dystopian place, truth becomes a casualty, and storytelling is treated as a seditious crime.

Chakravarty’s book is a fine chronicle of the pain and suffering of ordinary Kashmiris – or what the author herself calls “a story about stories told in Kashmir.” She discusses the history of and about the Kashmir conflict. There is the official history-writing by the Indian and Pakistani states, which speaks the language of a territorial dispute – much like Edward Said’s Orientalist project, romanticised according to each state’s version of the conflict. Then there is tehreek history writing, which offers a different, predominantly Kashmiri, perspective on the evolution of the dispute and questions the legitimacy of the territorial claims made by the two aggressive nations.

In these halaat stories, Chakravarty develops a narrative about how Kashmir’s culture of storytelling has survived the vicious assaults of various empires, cruel and ferocious monarchs, and the tyrannical power of an imposing state. Storytelling, in its varied forms, has long been a cultural practice – and, in the face of repression and the brutality of marauders who annexed Kashmir not merely to rule but to alter its indigenous history, culture, and language – it became an effective form of political dissent. Stories have been told by Dastangohs, Ladi Shahs, Bhands, self-styled Kashmiri folk artists in various formats, but often centred on the same theme – the oppression and tyranny of alien rulers who have been antithetical to Kashmiri subjectivity.

The heart of Kashmir

Chakravarty takes you on a journey into the cultural mosaic that Kashmir once was, where thousands would gather each evening under a mighty chinar tree to enjoy Bhand Peather performances and lose themselves in the lyrical flutes of Ladi Shah during the harvest season. However, this vibrant cultural tapestry abruptly vanished with the outbreak of militancy and the subsequent militarisation of the valley.

Chakravarty divides her book into four parts – “Laughing at the King,” “Possession,” “Loss,” and “Blood Maps”. In each section, she beautifully articulates zulm (oppression) in an evocative manner, making the reader a witness to this brutality. Kashmir's lived experience of zulm, as narrated through the personal accounts in this book, is multifaceted – physical, as seen in the presence of thousands of unmarked graves; psychological, with the region having one of the highest numbers of PTSD patients; and social, marked by a collapsed social fabric and deepening discord. Mahjoor, Kashmir’s national poet, while recounting the Kashmiri experience of tyranny, said:

“Nuun-dead gayos, National wannas,

Dopam godi rul Hindustanas saet,

Buzith ye wachem thar thar panas,

Kari kya, dil chu Pakistanas saet”.(I went to get salt, National Conference told me,

Become Hindustani first,

Hearing this, I started shaking,

what to do, my heart was Pakistan’s.)

Beautifully written and meticulously researched, Chakravarty’s Dapaan is a poignant exploration into the heart of Kashmir, offering a harrowing account of lives torn apart by the viciousness of a bloody conflict. Chakravarty has been reporting from Kashmir for years, and her reportage is bold, fair, and fearless. Her stories – narrated through humour, inventiveness, melancholy, and mythology – centre on Kashmiris, capturing their pain, suffering, and resilience in the face of an ugly war. These tales serve as a mirror to the bruised and broken lives of a Kashmir that is now officially claimed to be liberated, integrated, and normalised in government statements and popular media. She lends a human touch to stories of death and the destruction of livelihoods – stories that are often reduced to headlines and statistics.

Subjugation is physical in nature but is cemented through the mental control of the subjects. In the mid-1990s, a strange and haunting phenomenon emerged in Kashmir, further reinforcing the fear of psychosis. Ghosts – Raantas, Daen, and braid choppers – unleashed a new wave of terror on a people already traumatised by the violence of insurgency and counter-insurgency. The purpose was to enforce submission through haunting. As Frantz Fanon points out, “The colonial subject is dehumanised to such an extent that it turns him into an animal.” The author’s particular emphasis on documenting how seriously Kashmiris were terrified by these ghost stories makes this book a compelling portrayal of one of the darkest periods in the conflict-ridden region. She writes, “For a few months in 1993, there was a period of intense panic. The Halaat take the shape of a daen, invading towns and villages across the valley. The mass panic dies out in a few months, but tales of ghostly visitations crop up through the decades that follow. Stories haunt stories”.

In these bloodiest experiments to assert control over people and geography, generations of Kashmiris have suffered immense loss, and Chakravarty is attentive in detailing the disastrous consequences of these experiments. In Kashmir, the dead never fade from public memory and often resurrect in the mourning of new deaths. “Manz athas bam phatiyo / Ashfaq Wani lagiyo”, the bomb burst in his hand / Ashfaq Wani, I would have died for you, sang the boys in the memory of Kashmir’s first militant. Wedding songs, ostensibly sung to bless a couple as they embark on a new journey in life, often end in remembrance of the dead and those lost to the terror of an invisible monster. As Chakravarty puts it, “Wedding songs often became tombs for the dead after the Halaat arrived in Kashmir. They carried the memory of lost bodies”.

During the recent India-Pakistan conflagration, Kashmir once again became the subject of fierce debate, serving as a flashpoint that could trigger war between two nuclear-armed neighbours.

Chakravarty’s Dapaan is a tour de force of urgent political observation and stands as an unputdownable reference guide to understanding the heavy physical and psychological toll the clashing tides of nationalism continue to exact. Chakravarty may be a neabrim (outsider) – a euphemism outside journalists face for their biased reporting – but her treatment of Kashmiri subjectivity and her ability to interpret the historical injustices faced by the people make her a brilliant observer and an exceptional raconteur.

A fierce act of remembering, Dapaan rewrites the narrative of Kashmir with empathy, precision, and fire.

Bilal Gani is an academic and freelance writer based in Kashmir.

Dapaan: Tales from Kashmir’s Conflict, Ipsita Chakravarty, Context/Westland.