Tsutomu Yamaguchi and Charles Donald Albury died within months of each other. The former lived to the ripe old age of 93, and passed away in January this year [2010]; the latter died in May 2009, at the age of 88. Neither of them were household names in their respective countries, yet they were noticed in obituaries scattered across newspapers. However much newspapers have changed over the last few decades, surrendering their place to television, cable, the Internet, and the mobile phone as sources of news, information, and commentary, the obituary pages have survived the relentless drive that has turned newspapers into merely another vehicle for advancing commercial interests.

I was again reminded of Yamaguchi, whose obituary I first encountered in The New York Times, in August when the bells tolled, as they do every August 6 and 9, in remembrance of the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the mid-1960s, as a young boy living in Tokyo, I had no comprehension of what had transpired at Hiroshima. I wasn’t even aware that my father had visited Hiroshima, until, a few years later, when I was in my early teens, I chanced upon a book of photographs documenting the effects of the atomic bombing, evidently purchased by him at the museum of the atomic dome in Hiroshima.

Though the captions were in Japanese, the pictures furnished a terrifying record of the loss of human lives and the devastation of an entire city. Over the years, being drawn to the life and thought of Mohandas Gandhi, and, then, in the 1990s, witnessing India’s own tragic quest to become a nuclear power, the question of what Hiroshima and Nagasaki represent has never been far from my mind.

Ruminating over these matters a couple of months ago, the obituary of Charles Albury came to my notice. I knew at once that their stories, the stories of Tsutomu Yamaguchi and Charles Donald Albury, had to be told together. There is no other way to tell their stories, even if no one else should think of linking their lives. Yamaguchi and Albury never knew each other; neither was known very much, as I have hinted, to the outside world, even if their names are, or will be, indelibly sketched in history books in unlikely ways. They ought to have known each other, all the more so since Charles Albury was dispatched to kill not Tsutomu Yamaguchi, but the likes of him.

We cannot characterize Yamaguchi’s killing as a targeted assassination; some will even balk at calling it a killing, considering that Yamaguchi survived the attempt to eliminate him by close to 65 years and, more poignantly, outlived Albury. Indeed, Albury would never have known of Yamaguchi’s existence when he was sent on his mission, and I doubt very much that he knew of him at all before he died. If Albury did know of Yamaguchi, he seems never to have betrayed that knowledge or acted upon it in any way.

No bookie could have placed bets on Yamaguchi’s chances of survival and walked away with a bounty. After hearing Yamaguchi’s story, one might be a thorough non-believer and still believe in miracles. And, then, as if Yamaguchi’s life doesn’t already stand forth as eloquent testimony to the clichéd observation that “fact is stranger than fiction”, one is even more surprised to find the lives of Yamaguchi and Albury linked in the strangest ways. Even the gifts of a supreme artist are likely to be inadequate to describe their association.

Yamaguchi was a 29-year-old engineer at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, when, in the summer of 1945, his boss sent him to Hiroshima on a business trip. His work wound up in early August and he was preparing to leave the city on the morning of August 7. But before he could do so, the bomber Enola Gray dropped “Little Boy” on Hiroshima and flattened the city, killing 80,000 people. Yamaguchi survived the bombing: he was a little less than two miles away from “ground zero” when the bomb exploded, and he escaped with ruptured eardrums, burns on his upper torso, and in utter incomprehension at what had transpired. High up in the sky, Charles Albury, a First Lieutenant in the United States Air Force, was in the support plane behind Enola Gay: as Colonel Paul Tibbets released the bomb, Albury dropped the instruments designed to measure the magnitude of the blast and the levels of radioactivity.

From an altitude of over 30,000 feet, Albury would not have noticed the Japanese engineer. Yamaguchi could not have appeared as anything more than an ant from that immense height; at any rate, it is reasonable to suppose that the training of those charged with an extraordinary, indeed unprecedented, mission – one calculated to kill hundreds of thousands with the release of one bomb, exact an unconditional surrender from the Japanese, and showcase to potential future enemies the establishment of a new world order with the United States at its helm – would have stressed the necessity of shelving aside the slightest sentiment about feeling something for the hated enemy.

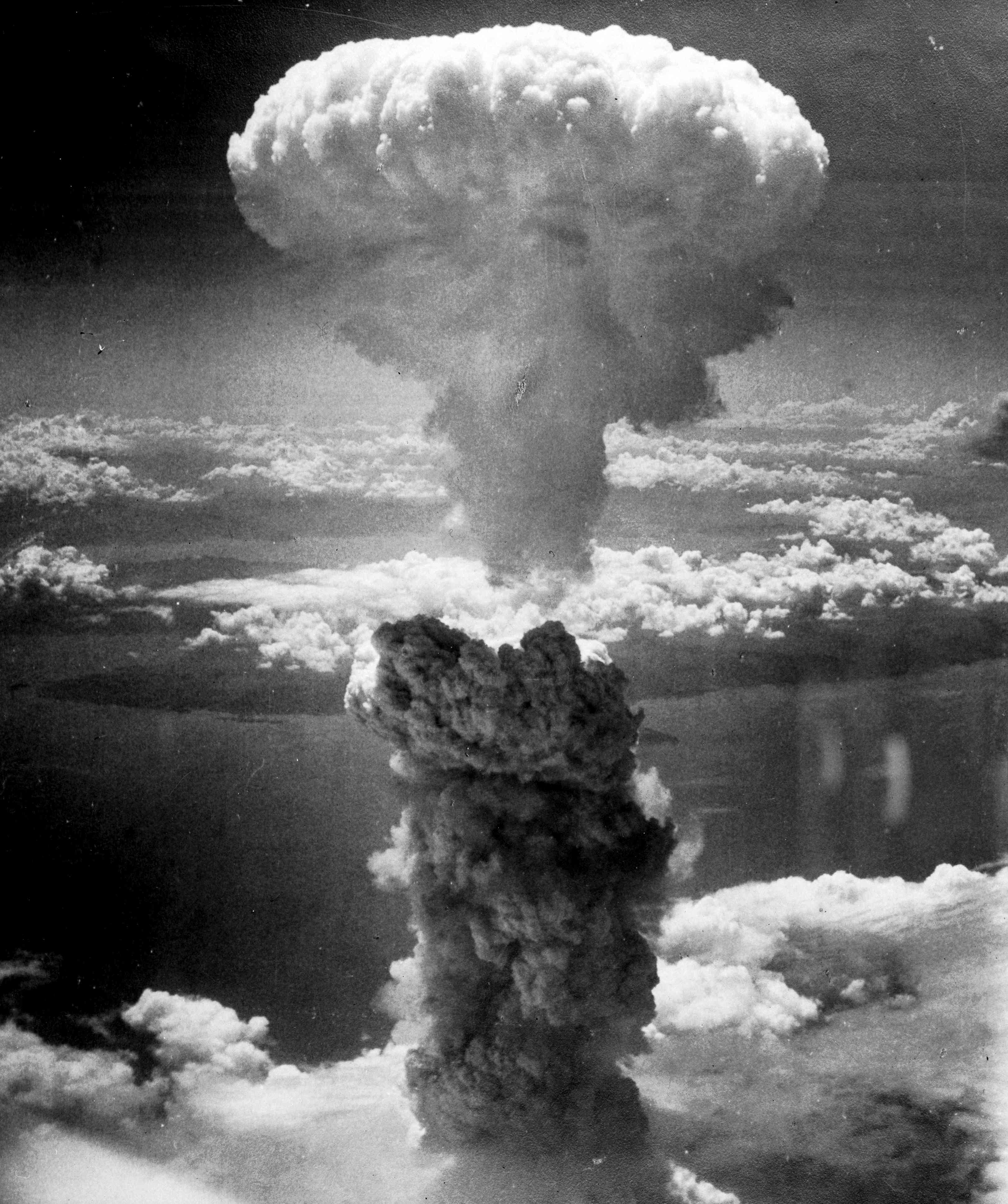

Albury did, however, have the presence of mind to notice that he was a witness to a spectacular sight: as he told Time magazine a few years ago, he dropped his instruments and “then this bright light hit us and the top of that mushroom cloud was the most terrifying but also the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen in your life. Every color in the rainbow seemed to be coming out of it”.

Robert Oppenheimer made a similar observation when the bomb was first tested in New Mexico. A more scholarly man than Albury, with some inclination for such esoterica as the Sanskrit classics, he noted that he was reminded of verses from the Bhagavad Gita when he saw the stupendous explosion – the splendor of which, akin to the “radiance of a thousand suns” bursting into the sky “at once,” turned his mind towards Vishnu: “Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds,” says Krishna (the incarnation of Vishnu) to Arjuna. There is, however, no reason to suppose that Yamaguchi, or any of the other victims of the atomic bombings, experienced anything resembling the beauty of a thousand suns or the most dazzling rainbows.

Unlike other survivors of the first atomic bombing, Yamaguchi had no reason to stay on in Hiroshima; he didn’t have to hunt for survivors among family or friends. So Yamaguchi headed home – to Nagasaki. On the morning of August 9, still nursing his wounds, Yamaguchi nevertheless reported to work. When his boss sought an explanation for his dressings and unseemly appearance, Yamaguchi began to describe the explosion and insisted that a single bomb had wiped out Hiroshima and much of its population. You must be mad and gravely disoriented, said his boss: a single bomb cannot cause such havoc and destruction.

At that precise moment, Charles Albury, co-pilot of the mission over Nagasaki, dropped the second atomic bomb, nicknamed “Fat Man”, over the city that had in the nineteenth century been Japan’s gateway to the West. Yamaguchi knew at once what was happening. He also thought, as he told an interviewer much later in life, that “the mushroom cloud had followed” him to Nagasaki.

Eighty thousand people would perish from the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, half of them instantly. Yamaguchi would become, one might say, thrice born, as he survived the blast. “I could have died on either of those days,” he told a Japanese newspaper only months before he died in January 2010. “Everything that follows is a bonus.” A new word, hibakusha, the explosion-affected people, was coined in Japanese to describe the survivors of either atomic bombing; and yet another phrase describes the “twice-bombed” survivors, known in Japanese as nijyuu hibakusha. Yamaguchi was the only officially acknowledged nijyuu hibakusha, otherwise believed to number around 165. I don’t believe that there is a vocabulary in any language that can describe what Yamaguchi might have gone through. Yamaguchi’s wife died from kidney and liver cancer in 2008.

His daughter describes her mother as having been “soaked in black rain” from the bomb. Her brother, born in February 1945, was exposed to radiation, and would fall a victim to cancer at the age of 59. Yamaguchi himself struggled with various illnesses but held on to life with tenacity and philosophical composure, displaying an equanimity that might explain the energy he displayed, at the age of over ninety, in finishing 88 drawings of the images of the Buddha, representing the same number of temples – or stations – encountered on a famous religious pilgrimage around Shikoku. Later in life, after his son passed away, Yamaguchi became an ardent critic of the nuclear race, and he denounced the obscenity of the possession of nuclear weapons.

Meanwhile, his mission accomplished, Charles Albury returned to the U.S. and became a pilot with Eastern Airlines, settling down in Florida. He would say, when questioned, that he felt no remorse: the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki had, he argued, saved hundreds of thousands of lives, Japanese and American lives that would have been needlessly sacrificed had the U.S. commenced a land invasion.

This argument is keenly contested, and many would argue that it has been discredited; one can even accept that Albury may have had good reasons to believe that his missions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki were calculated to save lives, though why he should have persisted with this view to the end of his life is another matter. When lives become part of a calculus of cost and effect, nearly every argument becomes permissible. Nor have we asked why a second bomb had to be dropped, when the Japanese high command had been thrown into utter confusion after the destruction of Hiroshima.

In 1982, while being interviewed for the Miami Herald, Albury stated that he opposed war, but would drop the bomb again if the U.S. were under attack. We know what such “opposition” to war means. “My husband was a hero,” Albury’s wife of 65 years told the Miami Herald after his death, adding: “He saved one million people. . . . He sure did do a lot of praying.” Since Charles Albury felt no reason to be contrite, one wonders why he prayed and, if he prayed, whether he prayed that he might become a better Christian or that the souls of the Japanese might be saved.

One of the most troubling signs of our times is the manner in which the loftiest words have become debased: where prayer is a private matter between the worshipper and his or her God, it has now been harnessed as a form of “spiritual warfare”. Members of the United States Strategic Prayer Network are committed to building a wall of prayer against enemies external and internal. Still, since prayer often retains its earlier characteristics, we should recognize it as a reclusive matter, a form of communication between the worshipper and the Divine, and thus allow Charles Albury the privacy of his religious beliefs and practices.

The Americans vanquished the Japanese. So goes the story, and it has many takers. The Chinese gained the respect of the Americans, Henry Kissinger once observed, when they became a declared nuclear power. Whatever cultural capital India may have thought it derives from being the land of the Buddha and Gandhi was evidently not enough when, in its quest for muscularity and military prowess, it exploded a nuclear bomb. We have shown them, a prominent Hindu nationalist leader was heard saying, that “we are not eunuchs”. The target of this missive was Pakistan, but India’s gigantic neighbor to the north also seems to have had its ears to the ground.

“Sad to say,” the author of a recent book on the Chinese communist party has admitted, “but India’s nuclear bomb gained New Delhi respect in Beijing. Certainly, Chinese strategists complained bitterly to me that Beijing did not respect New Delhi until India had the bomb.” It appears difficult to deny Iran its choice, if that is what it is, to embark on a program of nuclear armament when its two most vociferous critics, the United States and Israel, are armed to the teeth. It is all the more difficult, even reprehensible, to do so when it faces the threat of military destruction, and social and cultural annihilation, from the only country that has so far deployed nuclear weapons.

However, pondering over the twisted tale of Tsutomu Yamaguchi and Charles Albury, it is all but certain that political choices should not be confused with the will for ethical action and thought. The future of humankind will rest upon our capacity to rise above the base politics of the nation-state system and the idea that life is a zero-sum game. Not only is there no merit in being a superpower, but there is much greater merit in resisting the obscenity of a power unrestrained by wisdom, compassion, and intelligence. I believe one can never be certain who is the vanquisher and who the vanquished. All too often the vanquished have given birth to the vanquisher.

There are many possible readings, but when one places the stories of Yamaguchi and Albury in juxtaposition, it is quite transparent who represents the nobler conception of human dignity. The ontology of the vanquished, as the life of Yamaguchi shows, always has room for the vanquisher; the same cannot be said for the vanquisher. In this respect, at least, we might say that the vanquisher is always a lesser person than the vanquished. I would like to believe that Yamaguchi crossed over to the other side with an ample awareness of this fundamental truth.

Vinay Lal teaches history and Asian American studies at UCLA.

This essay was first published with the title, The Vanquisher and the Vanquished: Nagasaki and Two Uncommon Lives, in Volume 36 of the Amerasia Journal in 2010.