In 2003, a painted portrait of Hindutva ideologue VD Savarkar was installed in Parliament, sparking an uproar. Objections were raised over the fact that he had been accused in the Mohandas Gandhi assassination case, even though he escaped being charged in the conspiracy.

As the controversy raged on, it was also discussed by us members of Sahmat, the trust established in memory of activist-artist Safdar Hashmi. Sahmat ideologue Rajendra Prasad had found Savarkar’s book, The Indian War of Independence of 1857, in Delhi’s Teen Murti library. Banned by the British, the first edition of the book in English was published in 1909.

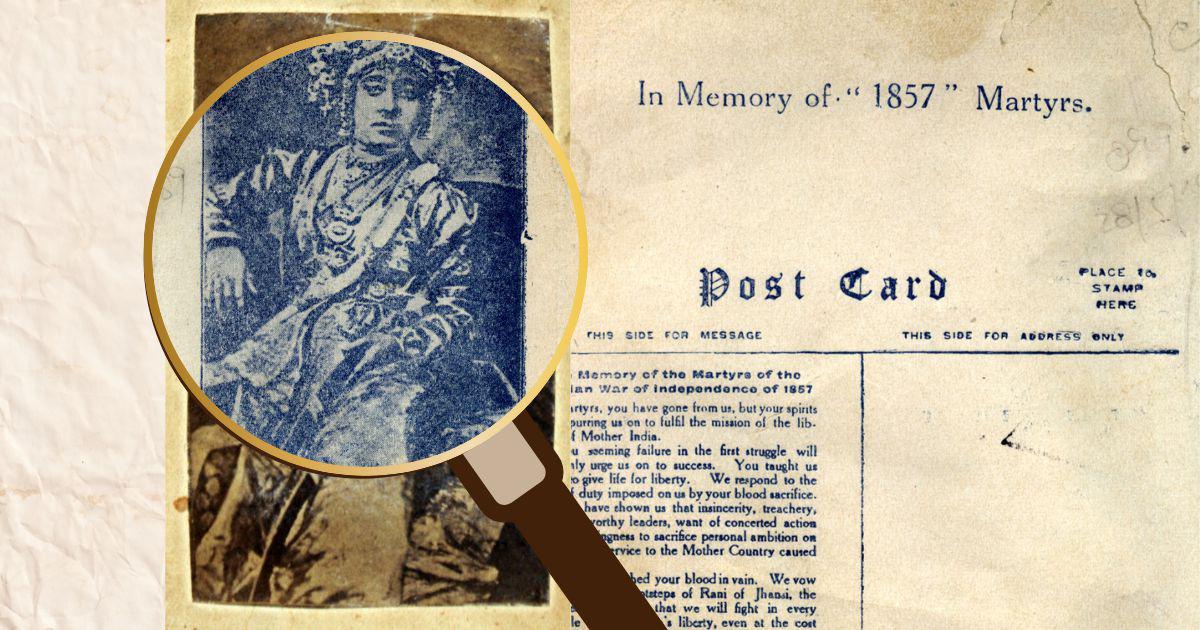

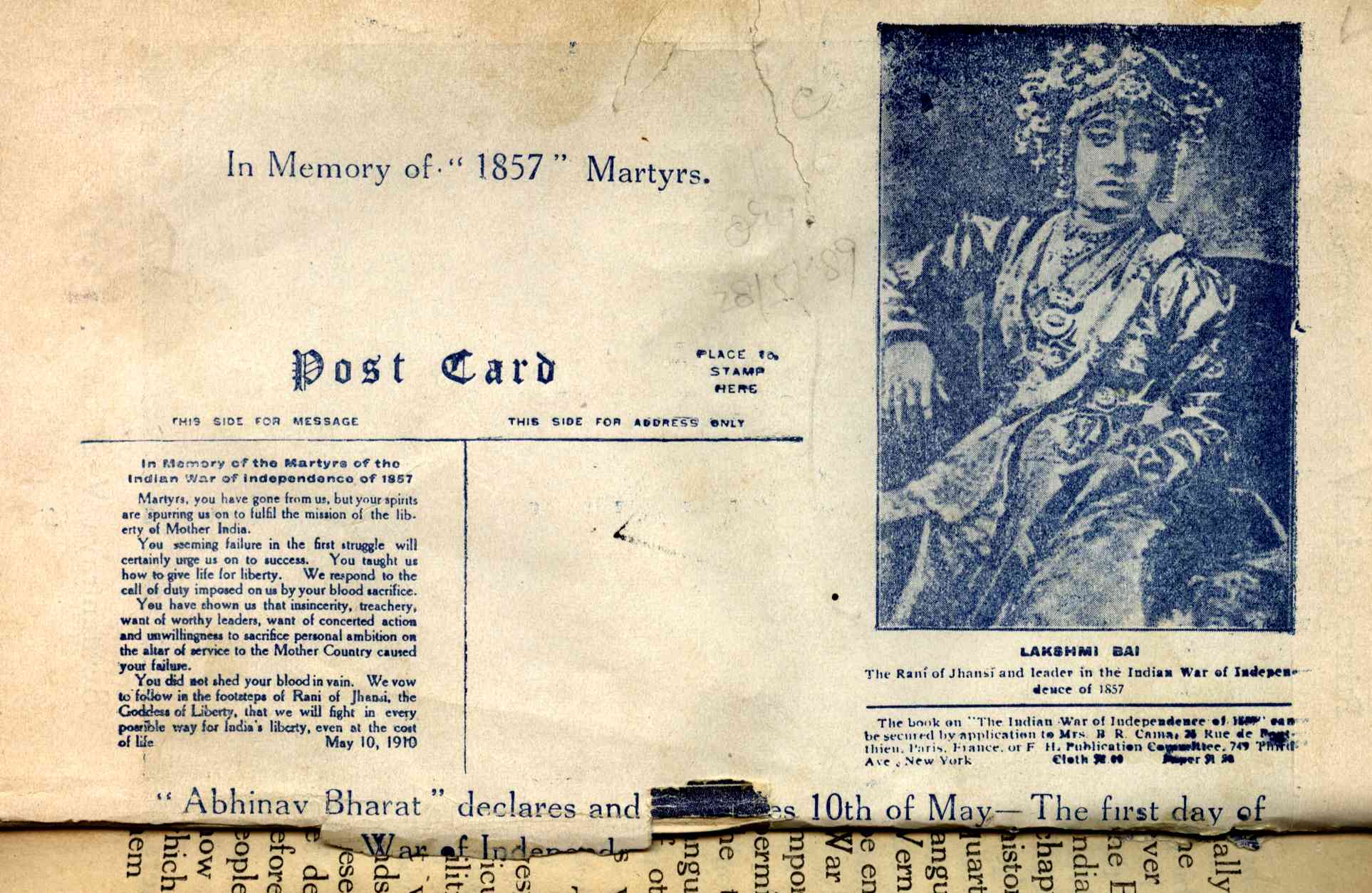

Leafing through the book I was astonished to see a reproduction of a postcard with a photograph titled “Lakshmi Bai – The Rani of Jhansi and leader in the Indian War of Independence of 1857”.

My heart raced. I thought I knew my photo history, but I had never seen this image or even a reference to it.

I had visited the Jhansi fort as a child with my mother and the vivid tales told by the guide were seared in my memory. I had grown up hearing the famous poem Jhansi Ki Rani by Subhadra Kumari Chauhan. I have also seen countless paintings and other images of Lakshmibai.

But a photograph, as an authentic portrait, would mean something else entirely.

While working on an exhibit on the Uprising of 1857 with Sahmat a little later, I included this image of the Rani and it travelled across India as part of the display.

Some years after this, in 2010, I saw a television news report about an exhibition in Bhopal with the same photograph, attributing it to an album in the collection of my artist friend Amit Ambalal in Ahmedabad.

I contacted Ambalal who told me that he had bought the album in Jaipur in the 1960s and sent me images of the pages.

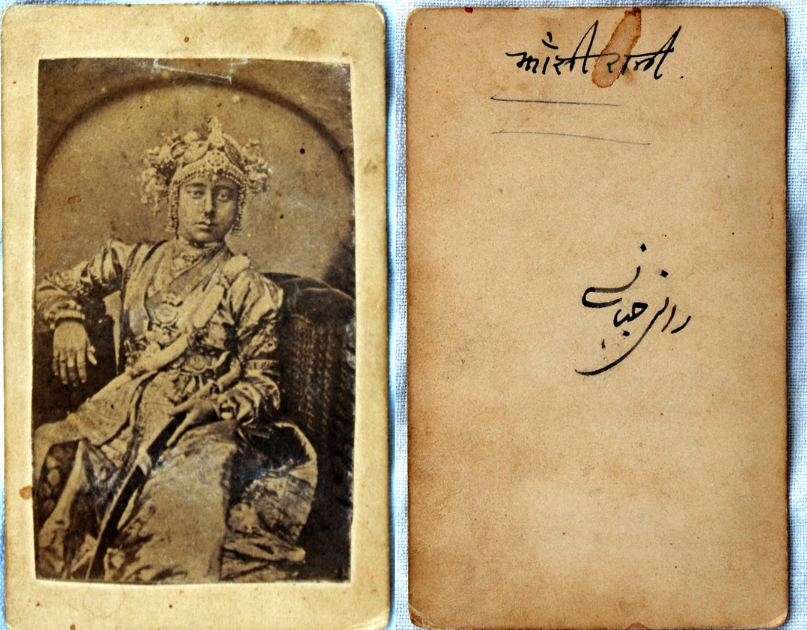

There, among photos and paintings of the other freedom fighters of 1857, was the Rani of Jhansi. Devanagari and Urdu scripts on the back of the photograph identified her. This was thrilling. There was now a second historical source of the image and, importantly, it was in India.

Excited by this discovery, in the following months I contacted many experts in the field to authenticate the image.

Could the Rani have been photographed?

Rani Lakshmibai had died in battle on June 18, 1858, but it was entirely possible that she had been photographed. Photography was fairly widespread in India by the mid-1850s.

I began a long search to authenticate the image and its source.

Around 2006-’07, I got in touch with photo historian Sophie Gordon, who was the curator of theatre director and collector E Alkazi’s extensive early Indian photography collection in London.

She had found an advertisement in a Delhi gazette shortly after the 1857 uprising, where there were photos of Jhansi offered for sale. But no images were traceable.

As part of my search into sources that could help verify the authenticity of the photograph, I had reached out to Bhawa Nand Uniyal, a collector of rare books from Delhi who was in London at the time.

I told Sophie Gordon that Uniyal had written back to tell me that he had found a post-Independence edition of Savarkar’s book in his collection stating that the postcard was not Rani Lakshmibai, but Begum Shahjahan of Bhopal.

“Now he finds this reference in the catalogue of proscribed material in the India Office Collections,” I said in my email to Gordon. “It obviously is not in the photography collection because it is a printed postcard. Are you still interested in this? Being there, you probably have much easier access to dig this up...it would be a terrific coup.”

I gave her the reference details Uniyal had sent me:

Listed item no: 176 in publications proscribed by the GOI

Reference no: EPP 1/36 IOLR

A catalogue of the collections in the India Office Library and Records and the department of Oriental Manuscripts & Printed books.

Edited by Graham Shaw and Mary Lloyd 1985.

Then, in 2010, I got a message from archivist and researcher Pramod Kumar KG, who found the same image in a photo album in the archives of the Chowmohalla Palace in Hyderabad.

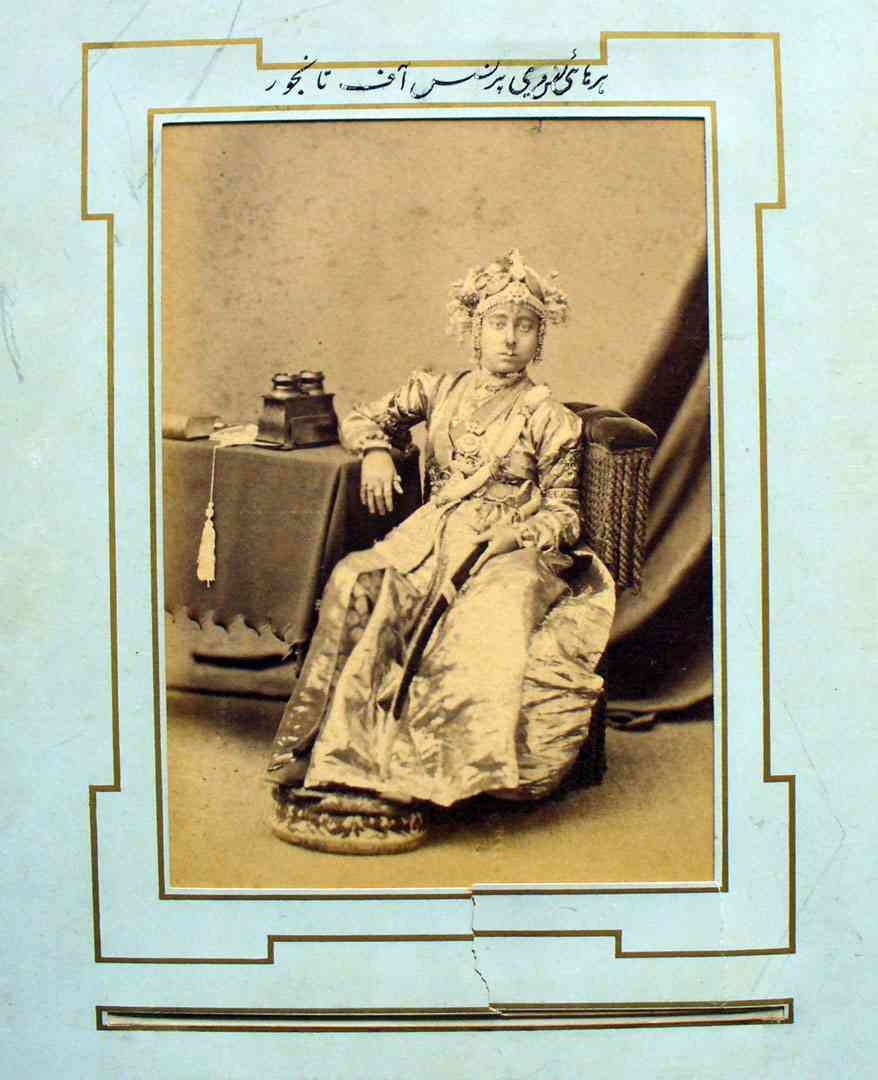

“This particular page has a carte-de-visite showing the lady in question seated on a chair. The caption in Urdu reads HH the ..... of Tanjore,” said Pramod Kumar’s message. “The main name is illegible though Her Highness and Tanjore is pretty clear. Looking at the image it is quite possible that this is the work of the Johnston & Hoffman Studio, here I am going by the props and the way the image is taken. Hope this helps clear the confusion.”

Shortly thereafter, a response from Sophie Gordon, by then the curator of photography of the Royal Collections at Windsor Castle, helped clear the matter up.

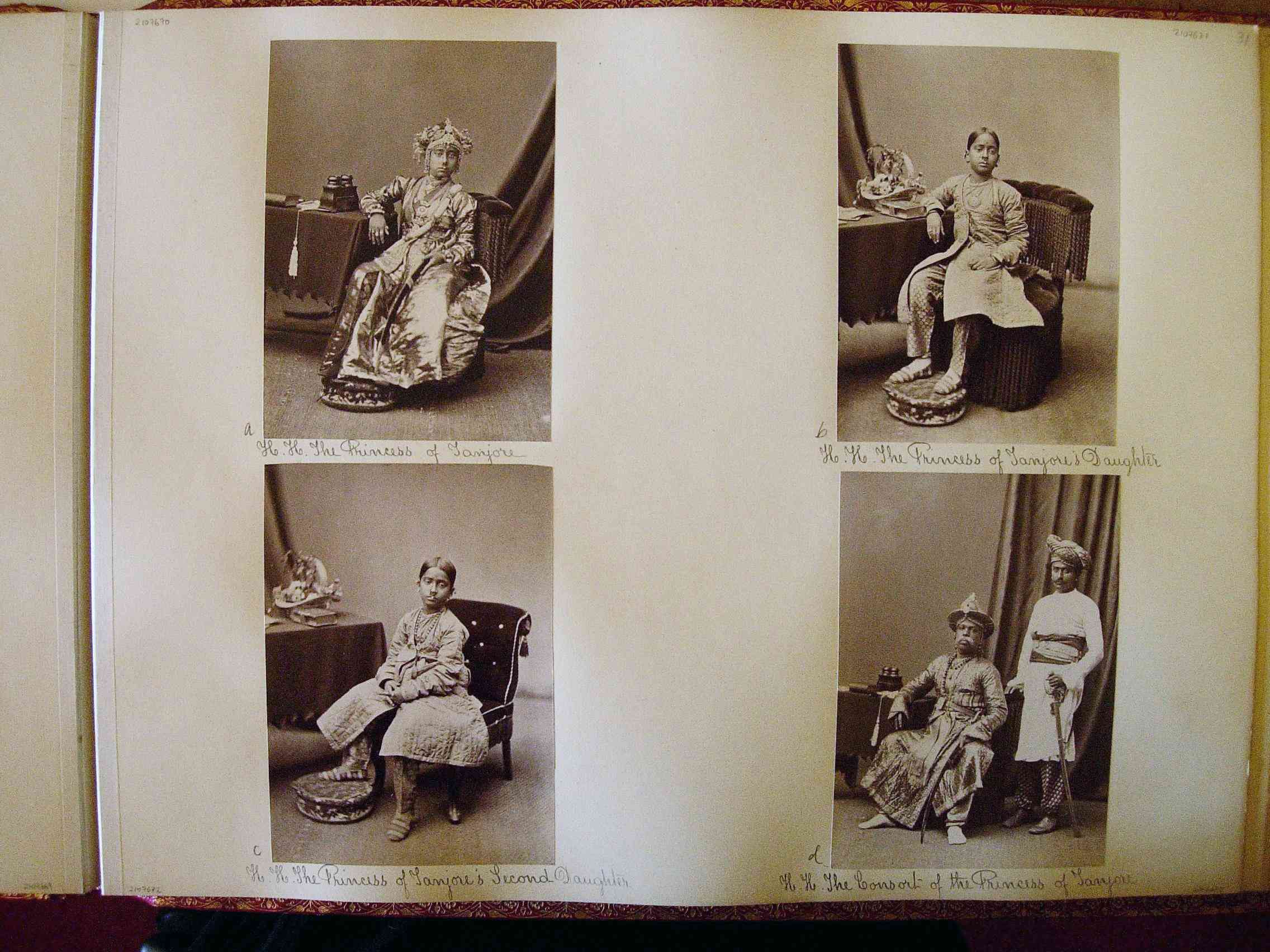

“The portrait of the woman identified as the Rani of Lakshmi is, as Pramod suspected, a princess of Tanjore,” wrote Gordon. “The Royal Collection has this portrait in the photograph collection where it is captioned as ‘HH The Princess of Tanjore’, from the Bourne and Shepherd studio. It is an albumen print (ie not a daguerreotype, and must therefore date to a later period). I should date to sometime in the 1870s.”

There was also an interesting history to the album.

“The portrait is on a page with other portraits of her two daughters and her official consort. The album itself is a collection of portraits of the many rulers of India, presented to Queen Victoria in the mid-1880s,” said Gordon, who had sent along an image of the entire album page. “Unfortunately, I have never seen a photographic portrait of the Rani of Jhansi. I hope this is helpful.”

Here ended the seven-year long search, from the Teen Murti library to Bhopal, Hyderabad, the India Office Library and finally Windsor Castle in England.

The image Sophie Gordon had sent was by far the clearest and showed other members of the Tanjore ruling family being photographed in the same setting.

It was amazing that this image had been in wide circulation at some point in the late 19th century as a photograph of the Rani of Jhansi. It was a testament to the power of her myth in the Indian imagination in our struggle for freedom.

Sadly, it was not the Rani. But the tale was worth telling.

It took seven years to hunt down the source of this photograph and even longer tell this tale. But in this age of artificial intelligence, misinformation, and fabrications, a search through 19th century archival material to authenticate history is even more important.

Ram Rahman is a photographer and curator who lives in New Delhi.