“People think anybody can recite the Bhagavata [Purana] and become famous,” Hemant Mani, 42, grumbled over the phone from his monastery in Dehradun, Uttarakhand. “Social media is giving people the freedom to pursue any profession they wish to.”

At the age of 16, Mani began training to become a reciter of Hindu religious scriptures, known as katha vachaks in the Hindi belt. He likened his craft to a yajna, or a ritual, which only Brahmin males could perform and scorned self-taught katha vachaks from any other caste or gender.

But, countered Manorama Singh Yadav, a katha vachak from Sitapur in Uttar Pradesh, why shouldn’t women recite kathas? “Many Brahmins come to listen to my kathas wherever I go,” she said. “They treat me like their own daughter.”

Yadav was born in a farming family but her interest in religion led her to kathas. She did not receive formal training in a gurukul – a traditional Hindu school – like Mani. Instead, she taught herself by reading books and listening to popular katha vachaks, first on television and then on the internet.

The flux in the profession came under the spotlight in June, when some Brahmins assaulted a band of backward-caste katha vachaks in Uttar Pradesh’s Etawah district. The state police sprang into action and arrested four Brahmin men two days later after a video showing them shaving the victims’ heads appeared on social media.

इटावा के बकेवर इलाके के दान्दरपुर गांव में भागवत कथा के दौरान कथावाचक और उनके सहायकों की जाति पूछने पर पीडीए की एक जाति बताने पर, कुछ वर्चस्ववादी और प्रभुत्ववादी लोगों ने साथ अभद्र व्यवहार करते हुए उनके बाल कटवाए, नाक रगड़वाई और इलाके की शुद्धि कराई।

— Akhilesh Yadav (@yadavakhilesh) June 23, 2025

हमारा संविधान जातिगत भेदभाव… pic.twitter.com/Pr11ohEp59

The incident stirred a debate that has divided katha vachaks across the country.

On one hand, celebrity preachers with millions of online followers, such as Jaya Kishori and the poet-politician Kumar Vishwas, have come out to say that Hinduism does not forbid people of any caste or gender from taking up this work. But some traditionalists like Mani, who ply their trade in small towns, told Scroll that the scriptures clearly say only Brahmin men can recite them.

The sole right of Brahmins?

Katha vachaks are unlike Hindu priests in that they are typically not involved in presiding over rituals or looking after temples. They travel from place to place reciting and interpreting Hindu scriptures, many of which are written in Sanskrit.

“They are like pracharaks of the faith,” explained Nivedit Bhatt, a priest at the Vindhyasini temple in Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh, using the Hindi word for preacher.

Today, katha vachaks recite texts such as the Puranas, the Bhagavad Gita and the Ramayana in people’s homes and public gatherings. But historically, in a time before the post, they also performed other crucial functions such as relaying messages and carrying herbal medicines from one place to another, according to Kalpna Bhatnagar, a Sanskrit scholar in Dehradun.

“Legend has it that Rukmini [Krishna’s first wife] used the services of a katha vachak to inform Krishna, her lover, about her brother’s plans to marry her off to someone else,” she said. “That is how Krishna eloped with her just in the nick of time.”

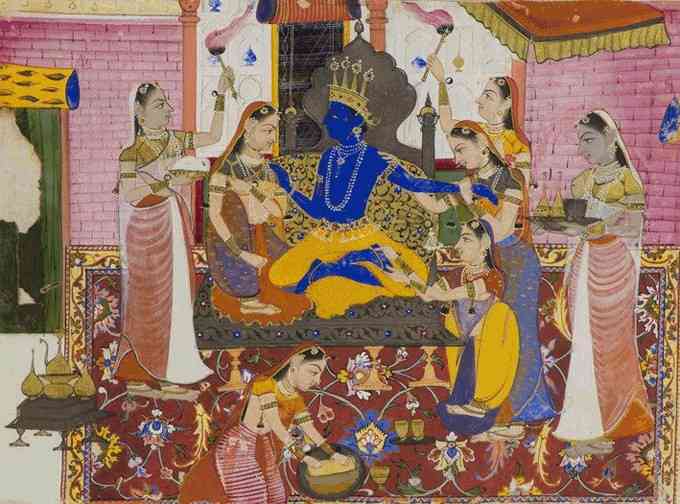

Of all the stories that katha vachaks tell, the Bhagavata Purana, revolving around the life of Krishna, is arguably the most popular one in the Hindi belt. Since Vyasa, the sage who wrote the Mahabharata, is believed to be its author, katha vachaks are considered to be occupying the Vyasa peetha, his seat, while reciting it. But the Vyasa peetha is also a site of contestation.

The primary source of conflict is apparently the text itself. A verse in the Bhagavata Purana says that only Brahmins who have renounced worldly pleasures and possess complete knowledge of the scriptures can recite it. Some Brahmin katha vachaks point to this verse to buttress their claim that they have the sole right to recite the Purana.

However, others contest this claim by arguing that the text does not require katha vachaks to be Brahmins by birth but by virtue.

“The Bhagavata Purana declares that those who worship god in the right spirit are Brahmins,” said a practitioner from a Dalit community, who did not wish to be identified. “To be a katha vachak, you need only have mastery over the text. You should be able to answer questions that crop up in the minds of devotees.”

Prying it open

Even as this katha vachak argued against caste-based restrictions on reciting kathas, he took an orthodox view on the question of language. Like traditionalist Brahmins, he too criticised self-taught reciters, who had picked up katha from the internet, for supposedly not doing kathas the right way.

He remembered that his university teacher, a Brahmin, had taught him to employ Hindi sparingly during kathas – only to translate the original Sanskrit verses. Those without formal training eschew this verse-translation format and use Hindi liberally, he complained.

But Yadav, the katha vachak from Sitapur, defended her use of languages like Hindi and Awadhi, saying they helped her listeners in following her message. Some of her most popular videos on YouTube, where she has over 1.7 lakh subscribers, show her narrating stories from the Ramcharitmanas in her mother tongue, Awadhi.

As a backward-caste woman who did not attend university, Yadav had struggled to find a teacher when she first started out over a decade ago. “In this day and age, nobody wants to share knowledge with others,” she said. “Nobody wants you to learn because they are afraid that you will rise up in life and do better than them.”

It was televised recitals and YouTube kathas that were critical in breaking caste and gender barriers, allowing Yadav the option of learning how to recite. In fact, she still uses YouTube to sharpen her skills.

“If you stop learning, you stop growing,” Yadav said.

Yadav is not alone. Several other backward-caste people are harnessing the power of social media to find their footing in what was historically a Brahmin-only occupation.

One such story is that of a katha vachak from the Nai community, a backward caste whose members are traditionally barbers. He met his teacher for the first time at an airport when they were both travelling for recitals.

“I am not a Brahmin,” the backward-caste katha vachak told him. “I learned how to recite the Bhagavata Purana by listening to you on YouTube. I consider you my guru.”

The anecdote was relayed to Scroll by a pupil of the guru – a Brahmin katha vachak from Vrindavan with lakhs of online followers. The pupil requested not to be identified but said his guru encouraged the backward-caste preacher to carry on doing what he does.

Lamenting the old ways

However, not all Brahmin reciters have taken kindly to this churn in their world caused by social media.

Some even accuse online katha vachaks of corrupting the craft by relying on jokes, music and folklore to embellish their kathas instead of sticking to the scriptures. Puneet Mishra, a 24-year-old Brahmin katha vachak from Mirzapur, said that these trends have led devotees to demand inventiveness from his traditional recitals too.

“Nowadays, even when people invite me to recite kathas, they request me to avoid Sanskrit verses and narrate anecdotes,” he complained. “There is no katha left any more. Now there is only singing and dancing. That makes other people think they can do it too. They see it as a chance to make a lot of money by entertaining the audience.”

Mishra further claimed that he was receiving fewer invitations for recitals than before. His last katha was in the month of March, he added.

Mani, the Dehradun-based Brahmin preacher, also articulated his anxiety about getting edged out by social media. As people from their profession entered the online realm, he lamented, they eventually succumbed to the logic of numbers and began prioritising entertainment.

“Audiences don’t care if scriptures are being followed as long as the katha is entertaining,” Mani said. “We, the Brahmins, can’t give people whatever they want. We have to adhere to the scriptures. That is why nobody is listening to us any more.”

He strongly rejected any suggestion that online katha vachaks were propagating Hinduism in their own way. “They are only promoting themselves online,” Mani argued.

Yadav, however, disagreed with his view. She saw no harm in preachers becoming famous so long as they imparted reformative values in their recitals.

“Without kathas, society cannot be reformed,” she said, advocating for more women and backward castes to take up the profession. “Our society cannot progress as long as some people continue mistreating others. We need to give up these thoughts and live together as equals.”