In every functioning democracy, the neutrality and credibility of its election commission is the oxygen that keeps the system alive. Without it, the act of voting risks becoming an empty ritual, and elected governments lose the legitimacy that flows from genuinely free and fair elections.

Around the world, when electoral commissions have been captured or compromised, the democratic fabric has frayed, sometimes irreparably. In Tunisia, the electoral commission’s refusal in 2024 to obey court orders reinstating presidential candidates undermined judicial authority and narrowed the field to the incumbent and two others, deepening the country’s democratic crisis.

In Pakistan, the Election Commission, aligned with the country’s military establishment and in blatant disregard for democratic norms and principles, barred former Prime Minister Imran Khan and numerous candidates from his party from contesting last year’s election.

In Bangladesh, revelations of corruption and procurement scams in the Election Commission eroded faith in elections, feeding an entrenched cycle of political cynicism, resulting in a popular uprising. In Afghanistan in 2009, the partisan composition of the electoral body and blatant ballot fraud led to a legitimacy collapse.

In Turkey’s 2017 constitutional referendum, allegations of ballot-stuffing and irregularities tainted the most consequential vote in decades. Belarus’s election body, in collusion with the authoritarian regime, presided over blatantly falsified results in 2020, sparking mass protests.

Each case shows the same pattern: when citizens no longer believe the umpire is neutral, politics becomes a zero-sum contest where the rules are bent to keep one side in power, and peaceful acceptance of results vanishes.

A counterexample

India was long held up as the counterexample, a sprawling, noisy democracy where the Election Commission of India managed the impossible task of delivering credible elections to over 900 million voters. Its model of independence and professionalism was studied globally, particularly by young democracies seeking institutional templates.

But that reputation is now under unprecedented strain. In the first week of August, Rahul Gandhi, the leader of the Opposition, accused the Election Commission of colluding with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party to “steal” elections through systematic voter roll manipulation, data suppression, and targeted irregularities in multiple states.

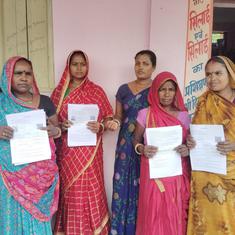

His charges are not just rhetorical flourishes: they are backed by detailed findings from a Congress research team that spent months sifting through voter lists, uncovering duplicate registrations, fake addresses, bulk voters at single locations, manipulated photographs, and suspicious spikes in turnout late in the day.

Gandhi’s claim that in the 2024 general elections the BJP retained power by winning 25 seats with margins under 33,000 votes, margins small enough to be swayed by the alleged “vote chori”, strikes at the heart of the commission’s credibility.

#RahulGandhi alleged that in Karnataka’s Mahadevapura Assembly constituency alone, there were discrepancies in 1,00,250 names in the electoral roll.

— Scroll.in (@scroll_in) August 7, 2025

Read more: https://t.co/N2kiYdlJkv#ElectionCommissionOfIndia pic.twitter.com/jWW8wYHUtQ

What makes this erosion of trust particularly dangerous is the institutional change that preceded it. In 2023, the Supreme Court had ruled in the Anoop Baranwal case that appointments to the Election Commission must be made by a three-member panel including the prime minister, the leader of Opposition, and the chief justice of India, a stopgap arrangement until Parliament legislated a new process. The point was explicit: insulating the appointment process from sole executive control to preserve impartiality.

But before a vacancy could arise, Parliament passed the Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners Act, 2023, replacing the chief justice with a Union cabinet minister chosen by the prime minister. This tilted the balance back towards the government of the day, undermining the spirit, if not the letter of the court’s ruling.

Critics warned this would allow the ruling party to shape the very institution meant to regulate it, echoing patterns seen in other democracies sliding towards competitive authoritarianism.

The government insists the new system is transparent and lawful, but perception is as important as process in electoral credibility. Once voters believe the referee is wearing the jersey of one team, even a perfectly administered poll can be rejected as illegitimate.

International democracy indices have already charted India’s democratic decline over the past decade, citing constraints on civil liberties, the shrinking space for dissent, and institutional capture. The Election Commission’s perceived partisanship adds a dangerous accelerant to that trend.

In the past, the commission’s firmness in enforcing the Model Code of Conduct that lays down guidelines for candidates and parties before polls, its readiness to censure ruling parties and its meticulous operational management allowed it to serve as a counterweight to political excesses.

Today, that image is fraying under accusations of selective enforcement, opacity in handling electronic voting data, and reluctance to address credible complaints.

खुल गई पोल !@cartoonistrrs #ElectionCommissionOfIndia #votechoriexposed pic.twitter.com/rYojRgsWvr

— Molitics (@moliticsindia) August 8, 2025

Research on electoral commission independence underscores that legal structures alone are insufficient. Formal independence, guaranteed by statutes or constitutional provisions, matters little if informal norms of impartiality are absent. Thailand’s 2019 elections are a cautionary tale: a formally independent commission insulated from day-to-day politics was quietly captured by entrenched elites, who used it to block political challengers.

Conversely, commissions in some African democracies, like South Africa, Senegal, Mauritania, even in Somaliland, with modest legal protections have earned respect through a culture of transparency, engagement with stakeholders, and willingness to stand up to the executive.

India’s own history demonstrates that both formal safeguards and informal norms are needed. The Election Commission’s golden years were as much about the personal integrity and public standing of its commissioners as about the legal provisions that shielded them.

The danger now is that India risks joining the list of democracies where the election commission becomes an extension of the ruling party’s political machinery. If allegations like those made by Gandhi gain traction without being credibly addressed, two outcomes are likely.

First, opposition parties will increasingly refuse to accept results, leading to prolonged political instability and eroding the peaceful transfer of power. Second, citizens may disengage altogether, convinced that their vote no longer counts, hollowing out participation in the very process that grants governments their authority.

This is not an abstract risk, it is exactly what happened in Bangladesh after repeated boycotts by opposition forces who viewed the electoral machinery as hopelessly rigged.

Restoring the Election Commission’s credibility will require more than dismissing allegations as baseless or politically motivated. It means embracing transparency, even if it means subjecting the commission’s processes to uncomfortable scrutiny. Providing machine-readable voter rolls, making VVPAT audit procedures public, preserving and sharing polling station CCTV footage, and allowing independent third-party audits of electoral data would signal that the commissionas nothing to hide.

Equally important is rethinking the appointment process to ensure that no single political force can dominate the selection of commissioners. Reinserting a judicial figure into the panel, as the Supreme Court originally mandated, would be a start.

Around the world, the collapse of public trust in electoral bodies has proven hard to reverse. In Tunisia, once hailed as the Arab Spring’s democratic success story, the politicisation of its electoral commission in recent years has coincided with a slide back towards authoritarianism. In Turkey, referenda and elections continue to be contested affairs where the losing side views the process as fundamentally unfair.

Bangladesh’s 2024 crisis showed that when the election body’s neutrality is gone, so too is the possibility of peaceful resolution to political disputes. India has not reached those extremes, but the many warning signs are there, and they are flashing bright.

The integrity of an election is not judged solely by the day votes are cast, but by the months and years of preparation, the fairness of the rules, the equality of access for all parties, and the independence of the body that oversees it. For decades, the Election Commission of India was proof that even in a vast, diverse, and contentious democracy, it was possible to conduct elections that all sides accepted as legitimate. That legacy is now in jeopardy.

The ruling party may see the commission’s control as a short-term electoral advantage, but history shows that once the referee’s whistle is distrusted, the entire game collapses. In the long run, no democracy, however dominant its incumbents, can survive the death of faith in its electoral umpire. India still has time to step back from that precipice, but doing so will require recommitting to the principle that the Election Commission must serve the Constitution, not the government of the day.

Ashok Swain is a professor of peace and conflict research at Uppsala University, Sweden.