“I want to ask you people,” Union Home Minister Amit Shah roared from the stage at a rally in Bihar on August 8. “Should infiltrators be removed from the voter list or not? Should the EC take strict action or not?”

Shah was speaking about the Election Commission’s special intensive revision of voter lists in Bihar, which was announced in June this year.

He suggested that the revision would delete the names of “infiltrators” from Bangladesh who had made it to the voter lists, a dog whistle for Muslim voters of the state. “Whom do you want to protect?” Shah went on, addressing Lalu Prasad Yadav of the Rashtriya Janata Dal and Rahul Gandhi of the Congress. “Infiltrators are your vote bank, that is why you oppose it [the voter list revision].”

Contrary to Shah’s comments, it is actually Hindu voters in Bihar’s Seemanchal region who have been disproportionately excluded from the draft voter list, when compared to their share of the population, according to Scroll’s analysis of data published by the Election Commission of India on August 1.

The Seemanchal region in eastern Bihar includes Araria, Kishanganj, Purnia and Katihar districts. Muslims constitute between 38% and 68% of the population in these districts. Hindu voters have been excluded between 6% and 9% over and above their share of population in these districts.

In the Assembly constituencies in the region, the highest exclusion of Hindus is in seats won by the Opposition parties in the 2020 Assembly elections.

There is no such comparable exclusion of Muslim voters in the state. It peaks in Sheohar, Aurangabad and Jehanabad districts, where the disproportionate exclusion of Muslims is at 1.8%.

Overall, our analysis shows that across Bihar, 83.7% of those excluded from the draft voter lists are non-Muslim and 16.3% are Muslim. Hindus and Muslims form 82.7% and 16.9% of the state’s population, according to the 2011 census.

Earlier, we had reported that five districts with a large share of Muslim population had among the highest exclusion rates. In four of these, we have now found that it is Hindu voters who have been disproportionately left out.

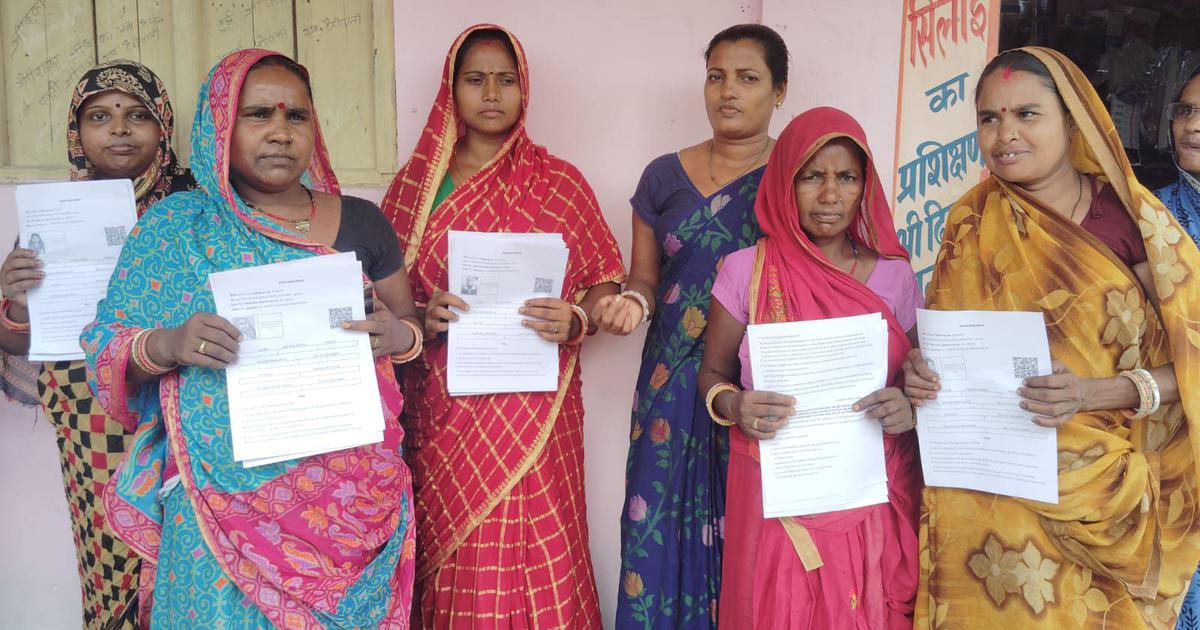

The draft voter list produced after the ECI’s intensive revision includes voters who submitted their enumeration forms to the poll body between June 24 and July 26. They will now have to produce proof of citizenship to make it to the final list that will be published on September 30.

Our methodology

Scroll has used a two-step process to determine the religious identity of excluded voters in Bihar.

In the first step, we compared two lists published by the Election Commission.

On July 16, the ECI published a list of voters who had not submitted their enumeration forms for the intensive revision. The ECI organised this data Assembly constituency-wise.

This list contained 1.49 crore entries – names of voters, their fathers or husbands, and their EPIC numbers, among other details.

On August 1, the ECI published the draft voter list which contained 7.24 crore names. The data was uploaded on a dedicated website called “Bihar SIR Draft Roll 2025” and was also organised Assembly constituency-wise.

Since both these lists were initially digital and machine-readable, we used a computer programme to extract names from both lists and compared their EPIC numbers.

Voters whose details appeared in both were those who submitted their enumeration forms between July 16 and July 26.

But the EPICs that appeared in the July 16 list and not in the August 1 list are those excluded in the draft voter list.

The computer programme generated the details of 64,85,945 voters — a few thousand short of the ECI’s official figure of 65 lakh excluded voters.

For the second step, we used another programme to determine the religious identity of the excluded voters. This programme, called It’s All in the Name, was published in Harvard Dataverse, a data repository hosted by Harvard University, in February 2023.

The programme uses the name of a South Asian person and their parent to infer if they are non-Muslim or Muslim by giving them a ‘Muslim score’.

It gives a Muslim name a score of more than 0. Non-Muslim names get a score of less than 0.

Among Muslim names, an ambiguous name gets a lower score and a clearly Muslim name a higher score. So, a voter named “Navisa” in Forbesganj got a score of 0.1. But another called “Md Irfan Alam” scored 1.5.

We fed the programme the names of the excluded voters and the names of their fathers or husbands.

For better accuracy, we set the ‘Muslim score’ at the conservative level of 0.3 to arrive at a more precise religious identity for every voter. In Seemanchal region, since the Muslim population is high, the score had to be adjusted to 0 to get more accurate results.

Of the 64.9 lakh excluded voters, the programme classified 10.6 lakh as Muslim and 54.3 lakh as non-Muslim.

Since Hindus form 99.48% of Bihar’s non-Muslim population, we will use the terms interchangeably in this story.

Findings

Our analysis shows that the intensive revision has had an outsized impact on Hindu voters in Bihar.

In 20 of Bihar’s 38 districts, Hindus have been excluded from the draft voter list over and above their share of population from the 2011 census.

This exclusion is most acute in the Seemanchal region, where the population of Muslims is between 38% and 68%.

For example, 57% of Araria district is Hindu. But the community forms 65.4% of voters excluded in the district’s draft voter list, a difference of 8.34%.

Muslims are disproportionately excluded in the remaining 18 districts, but the proportions are considerably smaller than Hindus.

For instance, 6.7% of Jehanabad district is Muslim. But 8.5% of those excluded in the district are Muslim – that is 4,315 voters.

In Gopalganj district, which has highest exclusion in Bihar in percentage terms, Hindus have been disproportionately excluded at 1.72%.

In Patna, which has the highest exclusion in absolute numbers, Muslims have been disproportionately excluded at 0.2%.

Assemblies

To further analyse the exclusion of Hindus in Seemanchal, we compared the population of Hindus and Muslims with their exclusion rate in 12 of the 24 Assembly constituencies of the region.

These are Forbesganj and Araria in Araria district, Amour, Baisi and Purnia in Purnia district, and Korha, Katihar, Kadwa, Balrampur, Pranpur, Manihari and Barari in Katihar district.

We selected these Assembly constituencies because they perfectly overlap with one or more blocks or nagar panchayats, for which the 2011 census provides a religious breakup of population.

The other 12 Assemblies that we could not analyse are made up of blocks as well as gram panchayats. The last census does not give data on religious groups in gram panchayats.

We found that the exclusion trends in Assembly constituencies are the same as those at the district-level. Hindus are disproportionately excluded in each of the 12 seats.

A closer look at the exclusion rate of Hindus in these constituencies shows that it is higher in seats that were won by the Opposition parties in the 2020 Assembly elections.

In seats with Bharatiya Janata Party MLAs, only in Korha constituency in Katihar was the disproportionate exclusion of Hindus close to 10%.