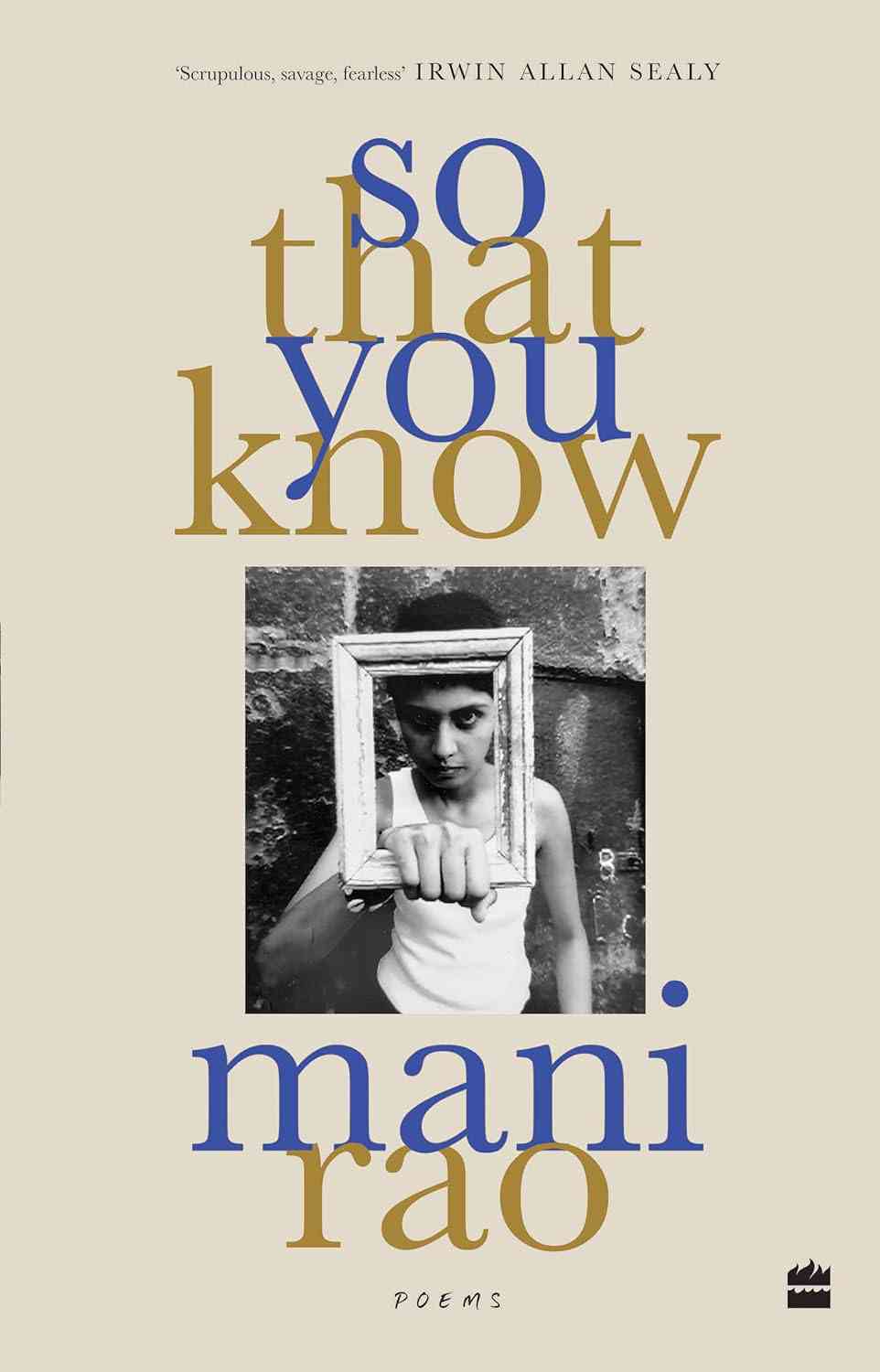

The poems of Mani Rao, one of today’s renowned poets, are known for their astute lines, closely observed details, and striking poetic images. They often leave readers smiling, wondering, awed, perhaps, with a sense of having discovered something elemental about “the human condition,” or about themselves. Their concrete images and crystal-clear coherence stay with readers long after. Her latest collection, So That You Know, launched at the 2025 Bengaluru Poetry Festival, carries all her signatures – and more.

The book carries new work as well as selected poems from eight previous collections, and avant-garde pieces, such as a staggering poem-essay on the life and work of noted American poet Lorine Niedecker, published elsewhere. It is a fascinating journey through Rao’s new and selected poems, written over almost 40 years.

Poetic truths

Curiously, the Preface begins with Rao recollecting an incident where a reader asked her whether, in real life, she was like the speaker of her poems. She clarifies that the somewhat mysterious, multi-layered relationship between life and art, and more importantly, between the speaker in poems and the writer of poems, cannot be reduced to a simplistic yes or no binary. Artistic or poetic truths often, though not always, expand upon and transcend the truths of their makers. Which is not to say that their makers lack truthfulness. Only that the writer of a poem may not have the same purchase, or power to reach a reader – emotionally, morally, temporally – as the speaker of the poem will, or indeed, a poem itself does.

To my mind, that reader’s troublesome question stemmed from a fundamental human impulse – to know what a poem means. And reducing the poem to the imperfect, flesh and blood person of the poet is one way, perhaps the easiest way, to mitigate this ambivalence of knowing, that ‘good poems’ often cause in our hearts. Rao ends the Preface by expressing her “need for privacy”. This perhaps means, she wants, like any other poet, for the reader to search for, engage with, and rely on the poems themselves to know what they mean.

Hence a lot of her new poems in the book explore what it is to “know”, and how that knowledge often transforms the knower, and if not the knower in the poem, then at least the reader of the poem, who, at any rate, is the other half of its meaning-making machine.

One of the facets of existence where this need to know – both the Other and oneself – manifests most strongly is in romantic relationships. Thus, Rao offers us a series of compelling, what I call “about love” poems (I borrow this term from a title of a poem in Arundhati Subramaniam’s book, When God is a Traveller). These “about love” poems are, by turns, exuberant, playful, seductive, or melancholic, depending on which page you land on. In “This Marriage”, seven lines capture the politics, through the image of an overcoat, of a marriage that has grown lukewarm with time. It starts with, “It’s not too cold, I know, / but I had nowhere else / to keep this overcoat”, and ends with, “So I just let it sit / upon my shoulders”. In seven lines, she captures the security, safety, and even obsolescence of marriages that often outlive their necessity, or fail to redress new necessities with time.

The voice of the poem, in its confessional earnestness, is reminiscent of the speaker of William Carlos William’s famous poem, “This is just to say”. If the questioner from the Preface were to ask Rao, what does it mean, then? Is she supporting or critiquing the institution of marriage? Rao would have perhaps replied, “make what you will of it”. This ability to either remain open to interpretation, or open new ways of interpretation, is one of the powerful characteristics of most poems in the book.

One also observes sudden changes of scale in poems, which lead to unexpected turns, and juxtaposition of disparate images, that, as a result, unexpectedly surprise the reader. In “So Yes, but No”, a poem about two “about lovers” who also happen to be poets, in the first line the reader stares at “two rivers laden / with lands and legends”, and suddenly, “Like two celestial objects / may we revolve around each other”, but then we are, “In any room, there’s only room / for a single poet. Take turns”. Throughout 12 of the 14 lines of the poem, these lovers do not meet, and the last two lines reveal that it was never feasible for them to meet, given that they are “poets”. Does it mean that poets are incapable of love, or egotistic, or worse, misanthropic? One wonders. Interestingly, the poem prescribes “taking turns”, suggesting the importance of recognising, respecting, and mutually giving each other space. We would never know for sure. And perhaps, that is the point. Rao’s poems complicate what “knowing” means, by destabilising the way we arrive at knowledge. To be precise, the poems challenge our elemental need for certainty in texts, in arguments, in narrative. They seem to be saying, that ambivalence too, is part of the human condition. Taste it, feel it, embrace it. Take turns.

Such ambivalence exists, most tellingly, in poems which contradict themselves, sometimes consciously, formally, and other times, through their argument structures. “Just Looking” uses anaphora, in the form of the phrase “there is no love”, to foreground what one is looking for, i.e. love, but that such love is not to be found anywhere (in my right pocket, left pocket, shopping cart, behind curtains, in the freezer, on the cutting board etc), and in this failure to “find love” the poem ultimately performs the paradox that love often eludes our grasp, existing in the spaces between, or beyond, our searches and desires. Such a poetics reflects a profound understanding of human emotions, inviting readers to engage with ambivalences interwoven in human emotions. Likewise, “Story Moon” is a hyperbolic, exaggerated meditation on the role of essential love-objects, or objects we think of as essential, in romantic narratives. In the poem, this object happens to be the moon, a staple cliché in love narratives across cultures. The poem begins with,

“Pair of lovers coupled

with a full moon –

formula for romance”,but soon enough, after,

“Silhouetted faces cradled

in a generous moon curve –

Pregnancy.”,we realise,

“If there is no moon, oh no moon, there is no

moon at all, where is the moon, there is no moon…

moon what’s a poet to do

without moon”,

The poem ends playfully, hysterically, exaggeratedly, making the reader wonder whether it is possible to conjure love, write about love, think of love, testify to love’s existence, without its associated objective correlatives. And suppose it is indeed possible to conjure love beyond the concreteness of its objects, what roles did such objects – love letters, old photographs, the first trinkets and souvenirs – play in concretely marking, manifesting, and objectifying love? Conversely, the poem may simply be mocking the overuse of clichés or critiquing the unnecessary emphasis on rituals and clichéd patterns of representation in love narratives, when in fact, love requires a very different dynamic to sustain. Read either way, most of Rao’s poems invite readers to delve into the ambivalences, the in-betweenness, the liminal spaces that lie between human emotions, experiences and what we make of them.

The dualities

Consider the poem, “Happily M”, which likens a “happily m / couple” to an apple who “blushing / for the tableau / shows no sign” of a worm eating its insides. Such precision! The poem ends with, “secrets buried / in the back garden/ ferment”. The word “marriage” is reduced only to its initial letter, m. Is there some symbolism in this? Perhaps. Working as a companion piece to ‘This Marriage’, the poem realistically foregrounds the ambivalences and difficult spaces in any marriage. The tableau motif indicates the performative nature of marriage. There is blushing too, and concealing of things that cannot be shown to the public. But whatever these secrets are, they are buried, they are fermenting. Reading along the grain, one could easily read the poem as a critique of marriages made merely to gain societal approval through show-off and performance of shallow rituals. However, to my mind, the last three lines, “Secrets buried / in the back garden / ferment”, indicate change, transformation. Fermentation, as a process, entails breaking down complex sugars to simpler compounds. Later, new materials emerge from this process – bread, yoghurt, beer. Perhaps, the metaphor suggests that beneath the pressure surface of societal expectations lies the potential for growth and renewal for any marriage, much like the fermentation process that transforms ingredients into nourishing staples.

Another facet of the collection that stood out to me was the “place poems”, such as “Waiheke Within”, “Vacay at Myrtle Beach”, “Kashi Triptych”, and “Tiruvannamalai”. Rao reconstructs space by chiselling images from words. Precision and clarity of her descriptions allow readers to immerse themselves in the landscapes she evokes, creating a vivid sense of place that resonates with emotional depth. Gaston Bachelard, in this regard, has written in his book, The Poetics of Space, that “space that the imagination has seized upon cannot remain indifferent to the measures and estimates of the surveyor. It has been lived in, not in its positivity, but with all the partiality of imagination”. In “Kashi Triptych”, the city of Kashi is reconstructed through meditations on the cycle of loss and rejuvenation that are imposed upon it by the images of the poem. In Kashi, where,

“shadows hover anxious

like dogs markingcorners of terraced ghats

as lovers drink mirrorsa curly soot rains

upon the free bereftand pundits claim

ashes still warmfrom midnight pyres

for altar coffers at dawn”

The quest for salvation commingles with concern for altar coffers. The poem sharply captures the duality of existence that is performed each day in the city, whose funeral ghats are busy 24x7. But it turns upon itself and expands what it set out to say, with the end lines,

“Ash can’t swim

Hangs on to algae on hulls

Falls into arms of coralsScraped and bitten by fish

Shat along gorges and flatsWhy else do river beaches shine”

Thereby showing how the act of dying becomes the prerequisite of living/sustenance. The poem is rich with dualities: dying–living, human world–natural world, movement–stasis, and so many more. This act of expanding upon itself, transcending its own boundaries, provides the poem with the potential to capture “fuller”, “deeper”, “higher” truths about human existence. And perhaps, that is why in the Preface, Rao subtly urges the reader to seek the meaning of a poem in the poem itself. As she writes, “You are multitudes”. And so is “good” poetry.

Mani Rao’s poems offer the space to encounter multitudes of meanings and possibilities of being, in all their rich, in-between ambivalences. Read them.

Ankush Banerjee is a poet, a masculinities studies research scholar, and Reviews Editor at Usawa Literary Review. His book of poems, Field Notes on Kindness, is forthcoming.

So That You Know, Mani Rao, HarperCollins India.