“They said a new temple is coming up in your village," recalled the scrawny farmer, who is in his mid-forties. "I said achchi baat hai: the village will get a chance to develop, there will be electricity and water, a new road will get built. I told them I have no objection to the temple. Mandir ke naam pe koi takleef nahi."

But didn’t the reporters tell him the temple would be dedicated to Nathuram Godse?

“They didn’t take his full name," Singh said. "They just kept saying Godse ka mandir. Some of us thought they were talking about godhe ka mandir.”

The naïve endorsement of a temple for horses resulted in serious consequences for the villagers. Soon after the reports appeared on television and in the newspapers, the police arrived in the village. “They held up the photographs published in the paper and went around looking for all the people featured in them,” said Ram Pratap Singh, the village sarpanch. "Since then, the village has been haunted by the ghost of Godse."

Legal case filed

Within days, court summons were served to 25 people, including Krishna Pal Singh, under section 107 of the criminal procedure code that allows magistrates to preempt a breach of peace. Extricating themselves from possible arrest meant hiring a lawyer at the cost of Rs 500 per person and getting friends and family members to furnish two bonds of Rs 50,000 each. The only person who could not get bail was Kamlesh Tiwari, the Hindu Mahasabha leader who had proposed the idea of building a Godse temple on his ancestral land in the village starting January 30.

It was his public declaration that had prompted reporters to visit Para. The sarpanch was away that day, else they would have learnt that Tiwari’s family had just nine biswas of land, or less than half acre, which was jointly held by the families of five brothers, and barring Tiwari, no one was interested in the deification of Mahatma Gandhi’s killer.

“If Mr Tiwari wants to worship Godse, he is free to do so at home,” said Divya Mittal, the sub-divisional magistrate of Sidhauli, the administrative block in Sitapur district in which Para lies. “But by talking about building a Godse temple, he had inflamed passions in the area, which could have led to a breach of peace. To prevent it, we served notice to him. Since no local person came forward to issue a surety in his name, he was sent to prison.”

The sarpanch told me that Tiwari did not live in the village. His father, an impoverished priest, had left the village when Tiwari was still a child. No one had heard of Tiwari in Sitapur, not even the most enterprising reporter, until his public statements on a Godse temple began to circulate, travelling from the block to the district, the district to state capital, eventually making news across the country.

Waking the dead

It is possible to critique the media's eagerness to ratchet up controversy, but then it was no marginal figure who revived the ghost of Nathuram Godse in public memory. Sakshi Maharaj, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s MP from Unnao in Uttar Pradesh, described Godse as a “patriot and nationalist” at a meeting in December 2014. Following outrage from the opposition in the winter session of Parliament, Maharaj retracted his statement, but the genie was out of the bottle.

Within a week, the Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha demanded that the government should provide public land for the installation of Godse statues. The organisation’s president, Chandra Prakash Kaushik, appeared on primetime TV shows to peddle the view that Godse was a nationalistic hero whose love for the country forced him to end Gandhi's life. The focus on Godse was so intense, it did not take long for an unknown figure in Uttar Pradesh to step forward with an offer of private land for a Godse temple. The chain of events laid bare the contradictions inherent in Prime Minister Narendra Modi's victory, and ensured, among other things, that the virulent ideas of a violent man became known to the children of Para, along with the rest of the country.

Electricity poles with snapped wires.

The road to Para village passes through mustard and wheat fields in the middle of which stand poles with snapped electricity wires. The closest primary health centre is eight kilometres away. The day I visited, just 12 children had turned up at the village primary school. They sat on plastic mats on the ground. The teacher absent-mindedly corrected notebooks while they fiddled with their books and pencils. Some picked lice from each other’s hair. Others picked up fights.

Officially, the school had 107 children on the rolls. The teacher, Rajendra Kumar Varma, blamed the poor attendance on the Godse controversy. “The police visits have scared the children,” he said. “Otherwise 50 children attend school for sure.” Why wouldn’t the children bunk school, the villagers asked, if the second masterji who lived in Lucknow rarely bothered to come to duty.

Sitapur borders the city of Lucknow, but its social and economic indicators are closer to those of Poorvanchal and Bundelkhand, the backward regions of Uttar Pradesh. The 2014 state human development report ranks it at 57 among 70 districts. A 2011 study by the central government found the district to be have the least food security in the state. This is not surprising: Sitapur was the epicentre of the foodgrain scam unearthed in 2007. According to the CBI chargesheet in the case, foodgrain worth Rs 35,000 crore meant for poor families was pilfered and shipped off to five countries: Nepal, Pakistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh and South Africa. Among those accused was Om Prakash Gupta, a six-time MLA of the Samajwadi Party.

Proximity to the state capital has evidently done little for Sitapur's development. “The government officials posted in the district are most often to be found in Lucknow,” said Richa Singh of Sangtin, a non-profit organisation. As it happened, the day I visited Sitapur, the head of the district administration was in Lucknow. The police headquarters was agog with chatter over the transfer of a senior police officer at the behest of a politician. The district's chief development officer had been suspended for his alleged involvement in a sex scandal.

BJP posters in Sitapur district.

In such a rancid atmosphere, it is easy to see why people came to invest their hopes in Narendra Modi during the 2014 national elections. “We could not vote for Modiji because we had family relations with the candidate of Samajwadi Party,” said Vijay Kumar Singh, a young man in Para village, “but our hearts were with him. After all, he had done miracles in Gujarat."

The Bharatiya Janata Party won in all four Lok Sabha constituencies of Sitapur district. Three of the candidates were grafted from other parties and the rhetoric of development was married with careful attention to caste. In Mohanlalganj, the constituency in which Para village falls, the BJP picked Kaushal Kishore, a former communist leader who was a minister in the Mulayam Singh Yadav government. Belonging to the Pasi community, Kishore drew the votes of Dalits, which complemented the Hindutva vote of the BJP.

While bringing together disparate constituents makes for good electoral strategy, such alliances often come under strain after the polls. Already, in Mohanlalganj, there is talk of Kishore antagonising Hindutva groups by declining invites for gau rakshaa (cow protection) events. A local journalist claimed Kishore was wooing Ram Vilas Paswan's Lok Jantantrik Party in preparation for abandoning the BJP. Kishore denied such a move, instead claiming he joined the BJP because Modi spoke the language of a "communist". "Modiji spoke about people's concerns, whether toilets, homes, jobs," he said. "He did not bring up a communal agenda." But the journalist was convinced that Kishore could not last long in the party if he continued to alienate Hindutva supporters.

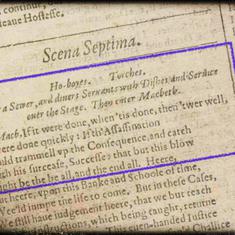

Godse statue in the Hindu Mahasabha office in New Delhi.

Even the Prime Minister can ill-afford to ignore the demands of Hindutva supporters, boasted Chandra Prakash Kaushik, the President of Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha when I met in his office in New Delhi. Seated in a high-backed chair against a saffron-painted wall, Kaushik, in his mid-forties, retained the manner of a property dealer, the job he held before he became the head of the Mahasabha. He was basking in the attention generated by the controversy over the statues of Nathuram Godse, one of which lay in a corner of the office. “I’ve been getting calls of support everyday,” he said, “many of them from abroad.”

The support could help revive the fortunes of the organisation, he claimed. Established in 1915, the Mahasabha had been the leading right-wing political party in the country until one of its members, Nathuram Godse, assassinated Mahatma Gandhi. After the assassination, the party split, with prominent leaders like Shyama Prasad Mukherjee forming the Jana Sangh, which later became the Bharatiya Janata Party. The Mahasabha went into decline and today its status can be judged by the fact that its headquarters in New Delhi doubles up as a venue for weddings.

The Hindu Mahasabha office in Delhi is rented out for weddings.

Despite taking different paths, the Mahasabha and the Sangh remain fellow travellers. A former president of the Mahasabha, Yogi Avaidyanath, was elected to Lok Sabha on a BJP ticket from Gorakhpur in the 1990s. His son, Yogi Adityanath, has inherited his political legacy.

Kaushik claimed to be in good terms with the Sangh, with regular “ram ram dua salaam” with its leaders. It was the work of Sangh's activists and the pro-Hindutva image of Narendra Modi, he said, that won the 2014 election for BJP, not the empty talk of development. "Whose vikas are we talking about when our nameplates are getting changed,” he said. Seeing my bafflement at his comment, he explained, “They came and built Qutub Minar in the place of Surya Mandir. Then they came and took over our properties at the time of Partition. Now, at the rate they are growing, they will change the name plate of your house to Abdullah Khan.”

According to Kaushik, Modi concurs with this view, but might feel compelled to foreground the rhetoric of development until the party has consolidated its numbers in Rajya Sabha and won more state elections. But to make sure he does not forget the real agenda, said Kaushik, it is the duty of the Sangh and its affiliates to keep up their reminders. “Bachcha rota hai to maa doodh pilaati hai. The mother feeds the baby when he cries.”

If this is what the Hindutva groups believe, the future is likely to see more such eruptions. At the receiving end will be people from minority communities and also those from the majority community who might unwittingly find themselves caught in the crosshairs of controversies and the attendant social conflict. The irony is that few among them will trace their troubles to the government at the centre. In Para village, residents remain enamoured of the Prime Minister, who they say has shown his worthiness by bringing down the prices of diesel and petrol.

As for the ghost of Godse, no one in the village has paused to think where it came from, even though it has created enough fear to drive people, even children, from the sight of a camera. The last time reporters took pictures in the village, people nearly went to jail, said the sarpanch. And so, the only pictures I was allowed to take in the village were those of animals.