A new, parallel skilling ecosystem is evolving in India to feed the starving $150 billion IT sector.

With advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence gaining ground, well-trained talent is increasingly difficult to find in the country. India’s universities don’t supply enough people who can hit the ground running, largely due to outdated curricula and a deficit of good teachers and other resources.

So, corporate India is chipping in, moulding a generation of non-collegian workforce. Both software companies and a host of training institutes are steering this trend.

Training freshers

Among the first to groom such talent was Chennai-based Zoho Corporation, which picked up high school dropouts, diploma holders, and just about anybody who demonstrated an aptitude for coding and other tech skills. For 12 years now, Zoho University has supplemented the software company’s talent needs with the right personnel, by now constituting some 15% of its 4,500-member workforce.

Software services major HCL began a similar programme six months ago, training high school students to perform IT tasks. India’s biggest software exporter Tata Consultancy Services has its TCS Ignite platform for training graduates from non-engineering courses keen on joining the firm.

In September 2016, IIT-Delhi alumnus Abhishek Gupta and autodidact Rishabh Verma launched NavGurukul, an institute that sponsors and trains students in software programming. NavGurukul runs a year-long residential programme in New Delhi entirely based on donations. It is experimenting with curriculum collated by industry professionals on an open-source platform. The courses are activity-based and taught by volunteer-teachers. The institute focuses on the underprivileged, with daily wagers and school dropouts on the rolls going on to secure tech startup jobs.

Meanwhile, constant upskilling and re-skilling remain an imperative at all levels of IT roles.

Need to re-skill

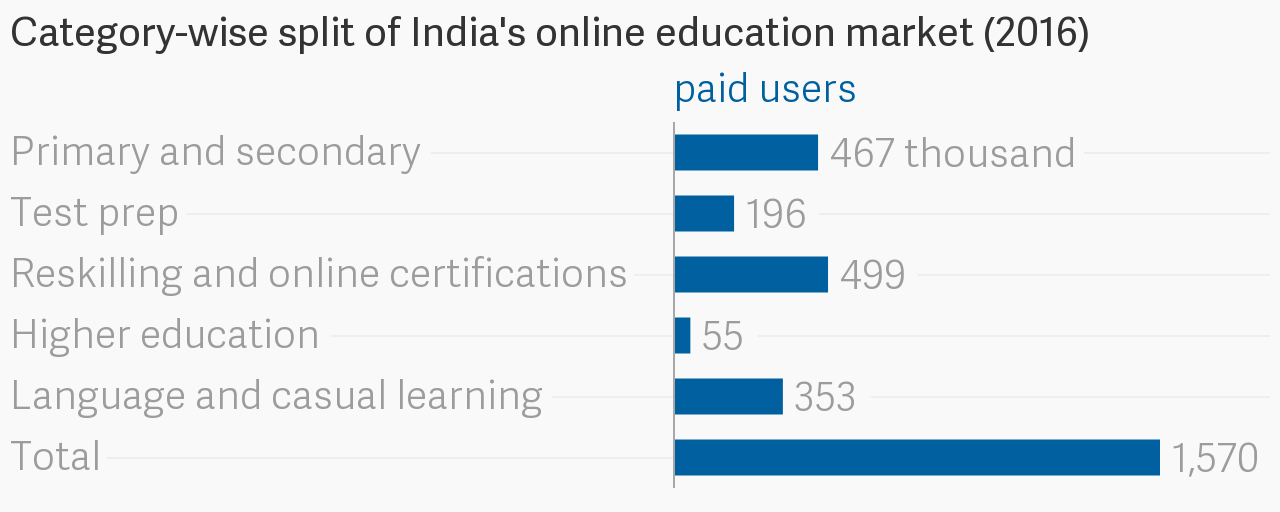

In the last decade, the online education space has flourished in India. And most of the paid users in this segment are those looking to re-skill themselves. The industry is set to be worth nearly $2 billion by 2021, up 10-fold from $247 million today.

US-based Udacity, Bengaluru-based Edureka and Mumbai-based EduPristine are among the many players offering paid certification courses to employees.

For entry-level positions, such courses offer expertise in advanced topics not taught in schools and colleges. Project-based learning, coupled with mentoring by professionals, helps convert “raw knowledge…to practical application,” N Shivakumar, business head of recruitment process outsourcing at Teamlease Services, told Quartz.

So far, it appears to be working well, with even large software companies like Infosys, Wipro, Honeywell, and Tech Mahindra working with online education companies.

Increasingly, conventional degrees are not being insisted upon by companies. For instance, e-commerce firm Flipkart hires people with a Udacity certification. Elsewhere in the world, too, firms like EY and PwC are scrapping the requirement for a formal degree, at least for some profiles.

In any case, it’s not like a formal degree in India entails good training or talent.

Fixing education

Most Indian tech graduates aren’t industry-ready. Companies feel that colleges provide context-less education and only a fraction of India’s fresh engineering graduates are employable. This is primarily because of a deficit of good teachers; owing to the dismal salaries, tech professionals mostly choose corporate jobs over academia.

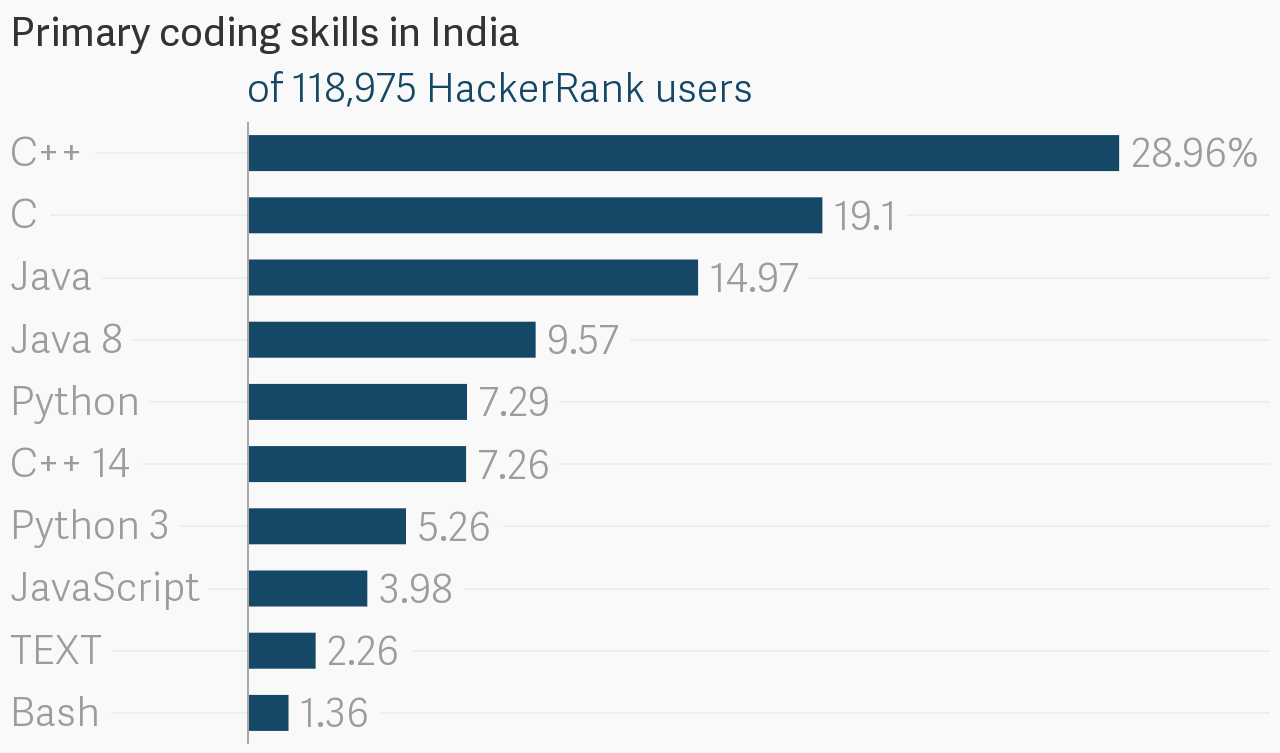

Besides, the focus in Indian IT education has largely remained on legacy programming languages such as C, C++, Java, and Visual Basic, even though new-age languages like JavaScript, Golang, Python, Ruby, CPP, Lisp, or Racket are more prevalent now globally.

Then there is the question of affordability of higher education. In any case, only a segment of “qualified” personnel that India’s institutes of higher learning churn out really fit into the rough and tumble of the professional world.

“Five or 10 years ago, it was enough to walk in with a piece of paper [certificates]. They’ll learn on the job and they’ll get better. That used to be the paradigm,” Mohan Lakhamraju, co-founder and CEO of Gurugram-based training platform Great Learning, told Quartz. “Not anymore. People want you to work from day zero. The day you come in, you need to contribute.”

The pitfalls

However, not all knowledge available on online platforms is disseminated effectively, making it important that learners find areas that best fit their specific needs and schedules.

For a working professional, time is important. “They can’t spend 100 hours to learn something in a very unstructured pattern,” Loveleen Bhatia, co-founder and CEO of Edureka, told Quartz. And free lessons from multiple platforms compromise standardisation and legitimacy – the things that employers value a lot. Moreover, getting academics and industry leaders to devote time on online platforms is expensive, which the free-to-use websites can’t afford.

Another drawback of the sponsored training model is that it could result in the employees getting “locked in” to a specific company’s ecosystem. On switching jobs, they may have to learn a whole new set of skills or completely relearn existing ones. This may only exacerbate the problem in the long-run.

This article first appeared on Quartz.