Humans have always been in the prediction business: we want to know what comes next. We haven’t always listened – the warnings of Cassandra from Greek mythology were doomed to be ignored – and throughout history and across cultures, the only vision of the future was one of the end. For many classical Western artists, depicting “the future” meant painting scenes from the Book of Revelation; Michelangelo, Albrecht Dürer, and Hieronymus Bosch reminded the viewer that life on Earth was finite, a handy reminder from the church to keep in line.

If the future was both fixed and apocalyptic, pre-modern writers and artists looked sideways to consider the existence of more advanced cultures. When much of the world was still uncharted, it felt conceivable that there could be a land inhabited by a fantastic civilisation just over the horizon. The Greeks had Hyperborea, the inhabitants of which could live for a thousand years. Thomas More had Utopia, essentially a socialised state. Jonathan Swift had the floating island of Laputa, kept afloat by “magnetic virtue.”

But by the 19th century, global imperialism had shrunk those “uncharted” spaces. At the same time, rapid advances in science and technology laid the frameworks for other possible futures – as well as increased anxieties about what those possibilities could bring. And as people started to imagine it, artists started to translate those ideas to the page.

When we think of futurists, we often think of scientists, science fiction writers, and industrial leaders. But what of the contribution of visual pioneers? Artists straddled science, design, and the traditions of pulp art, looking at the day-to-day possibilities that could change our lives. How did sharing these ideas, through advertising and media, shape our evolving picture of what the future would look like? And how did the world around them shape their ideas of the future?

Flight of fancy

Our contemporary idea of the future has mostly been shaped over past two centuries. Before the 19th century, technological change over the short human lifespan was minimal and most people lacked the leisure time to sit back and think about abstract concepts like the future. Perhaps more importantly, there could be perilous consequences to voicing ideas that challenged commonly-accepted doctrine on reality. Suggesting that the Earth orbits the Sun, or that there might be life on other planets, were factors that lead to Italian philosopher and cosmological theorist Giordano Bruno being burned at the stake in 1600.

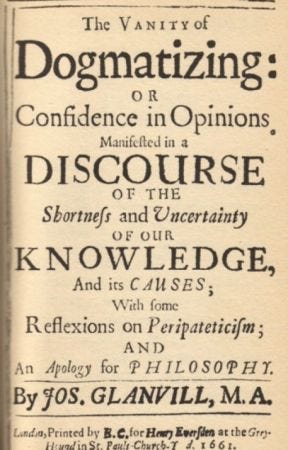

Over time, people began to be able to voice these dissenting ideas without punishment – and some started to look towards the future. Sixty years after Bruno, English philosopher Joseph Glanvill took huge leaps when he proposed that one day, a voyage to the moon “will not be more strange than one to America” in his 1661 book The Vanity of Dogmatising. His concept of global communication through “magnetic waves” predated the electric telegraph by 176 years.

The 19th century brought us closer to Glanvill’s future, as brand-new technologies were introduced at a rapidly accelerating speed. Their potential influenced fiction: flights of the first aeronauts inspired Jules Verne’s Five Weeks in a Balloon; experiments with electricity and galvanism partly inspired Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; and HG Wells, whose Anticipations covered everything from the mechanical modernisation of war to the reorganization of class structures, hoped his ideas could “undermine and destroy the monarch, monogamy, faith in God & respectability & the British Empire, all under the guise of a speculation about motor cars & electric heating.”

Nineteenth century artists were also getting in on the futurism game. In the preceding centuries, art was mainly concerned with capturing and interpreting reality, or the metaphysical, through religious and mythological imagery. But excitement about the technological leaps of the present – and potential leaps of the future – spurred us to want to see it.

Our desire to conquer the air has been a long-held obsession – from Icarus and his wings to Leonardo Da Vinci’s 1493 drawing of an aerial screw – yet the first practical flight would not occur until the Montgolfier brothers’ hot air balloon ride in 1783. This event became a catalyst on writers and artists to explore new frontiers: Verne and Edgar Allan Poe published tall stories of aeronauts, even travelling to the moon in Poe’s “Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall.”

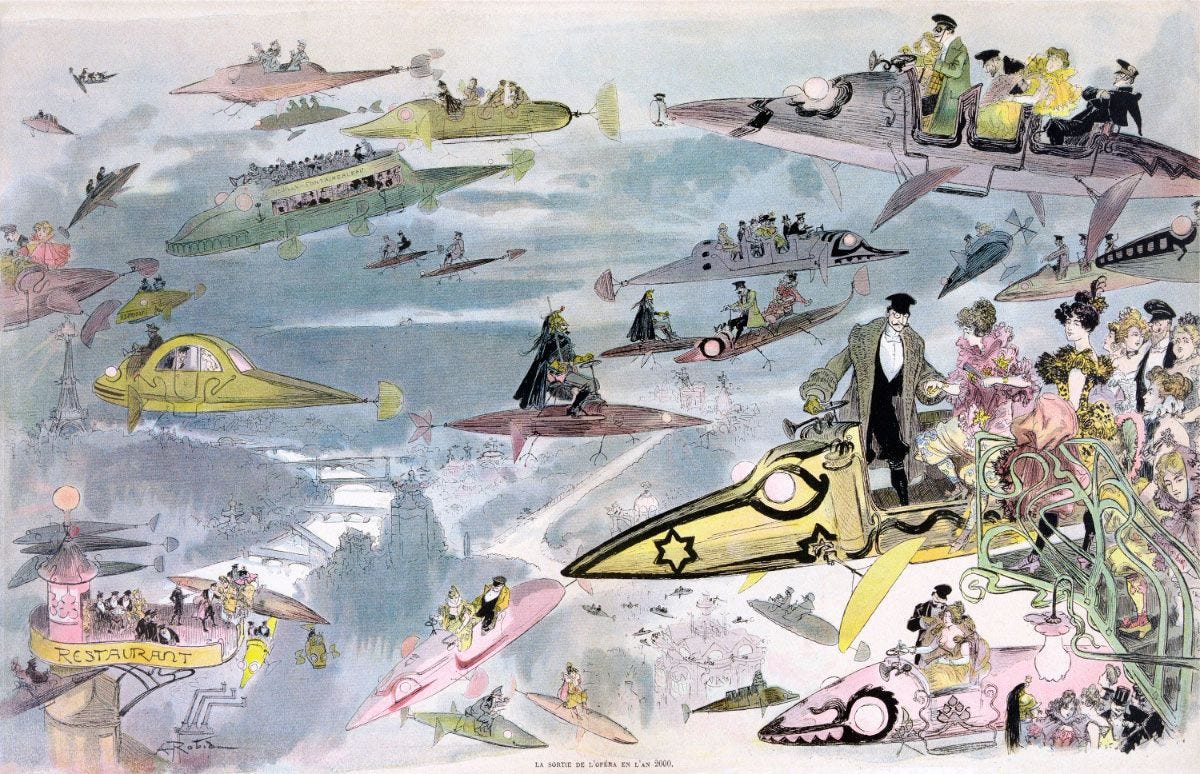

Early futurist artists filled their skies with flying devices of varying size and purpose. Writer and illustrator Albert Robida envisioned a time of personal flying machines used for jaunts to the opera, airships for public transport, and even luxurious floating casinos.

While flight was a major thread through his work, he devised other devices that would become integral to everyday life, like the Téléphonoscope, from 1890’s The Twentieth Century: The Electrical Life, a screen for entertainment like live opera broadcasts or reports from a battlefront. It even predicted interactive functions like home shopping.

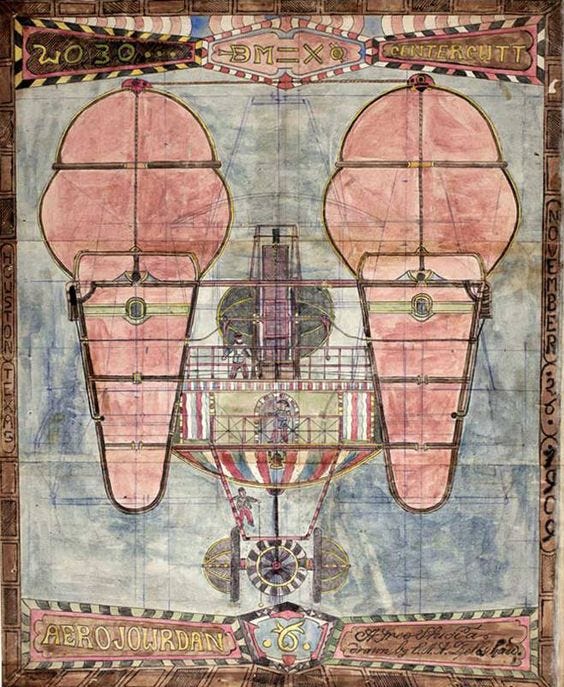

Enthusiasm about this emerging world was not solely reserved to professional artists. Between 1899 and 1921, Charles Dellschau, a retired butcher who claimed to be a member of a secret society called the Sonora Aero Club, filled 13 notebooks with 2,500 drawings, paintings, and collages of ideas for air travel and airships. Rescued from a landfill decades later, they were eventually shown to the public in 1969 – the same year that humans first landed on the moon.

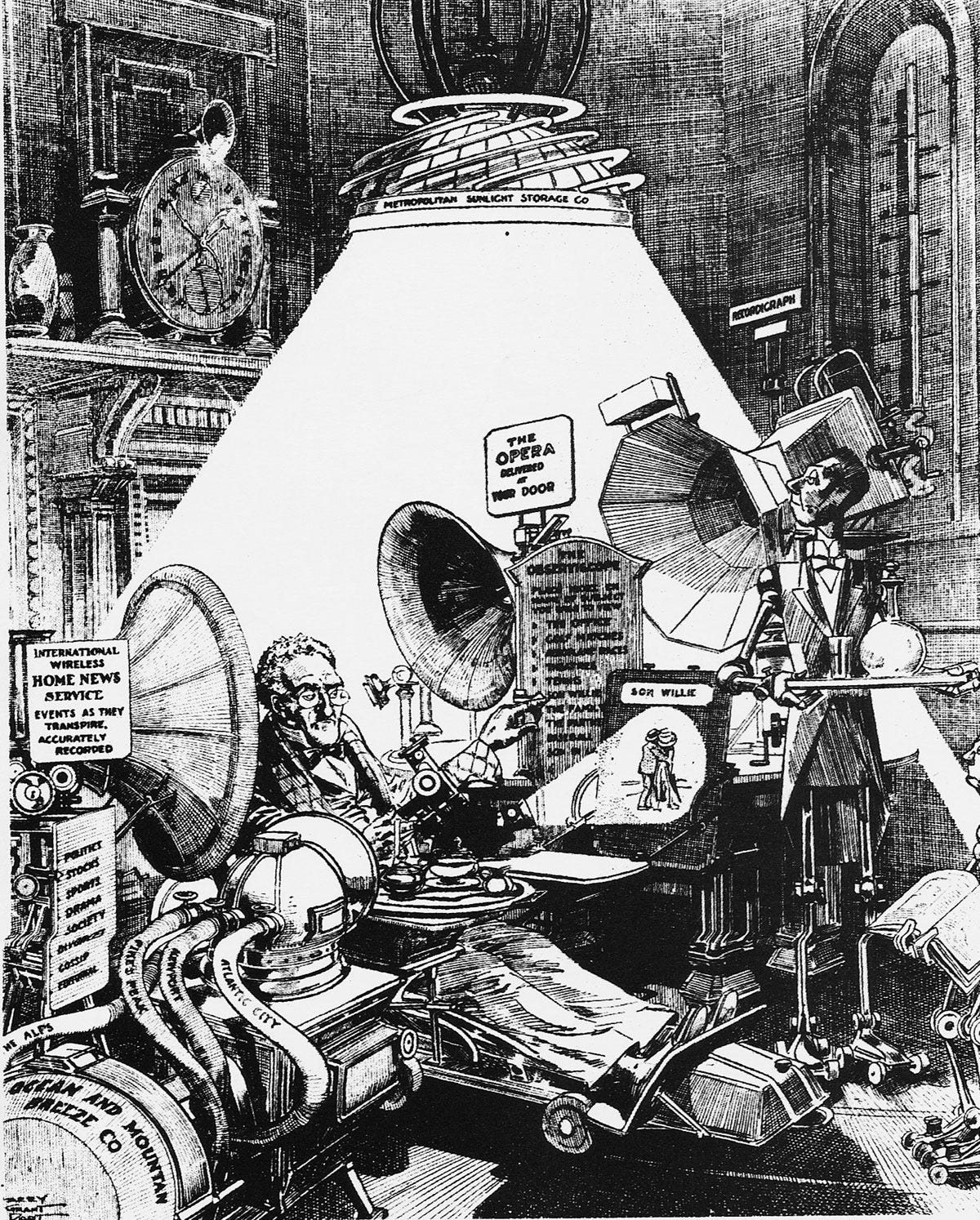

The romance of flight was also a preoccupation of illustrator Harry Grant Dart, who created his own airship comic strip, The Explorigator, in 1908. He was also a cartoonist for Life and Judge magazine, where his satirical cartoons were less optimistic than many of his futurist contemporaries, channelling anxiety and paranoia about where technological change might lead.

We’ll All Be Happy Then shows a mishmash of devices designed to enhance our domestic life: stored sunlight overhead, fresh air pumped in from the Alps, opera delivered to your speaker, 24-hour news with “events as they transpire, accurately recorded.” It also has one of the earliest examples of a robot servant: the gentleman of the future would never have to leave the comfort of his motor-powered armchair.

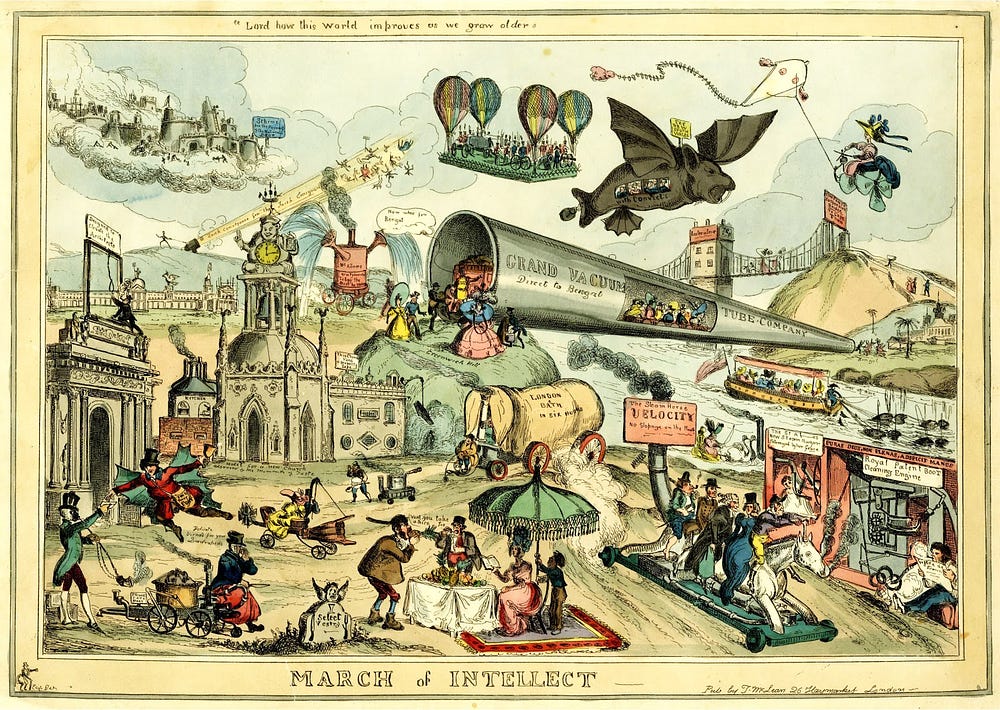

In 1824, industrialist Robert Owen coined the phrase “the march of intellect” to reflect the recent strides made in human knowledge, highlighting the benefits of technological progress that he hoped could lead to sweeping social change. His excitement was openly lampooned in a series of prints by William Heath: with mocking enthusiasm, Heath depicted a plethora of future transport methods, including steam horses, vacuum tunnel transport from London to Bengal, flying mail carriers (which would become a futurist trope), and Irish immigrants being fired from a giant cannon (reflecting topical social prejudices).

Challenges to the status quo and possibility of progressive social change was something periodicals reacted strongly to throughout the 19th century. In 1888, American journalist David Goodman Croly predicted that, “Women throughout the world will enjoy increased opportunities and privileges. Along with this new freedom will come social tolerance of sexual conduct formerly condoned only in men.”

Outrage at the havoc this future would wreak was reflected in a cartoon by Harry Grant Dart entitled “Why Not Go to the Limit?” Drawn at a crucial time for the women’s suffrage movement, he predicted where such progress would lead: bars full smoking, drinking, gambling women, ignoring their children and relegating men to the “Gentleman’s Parlour.”

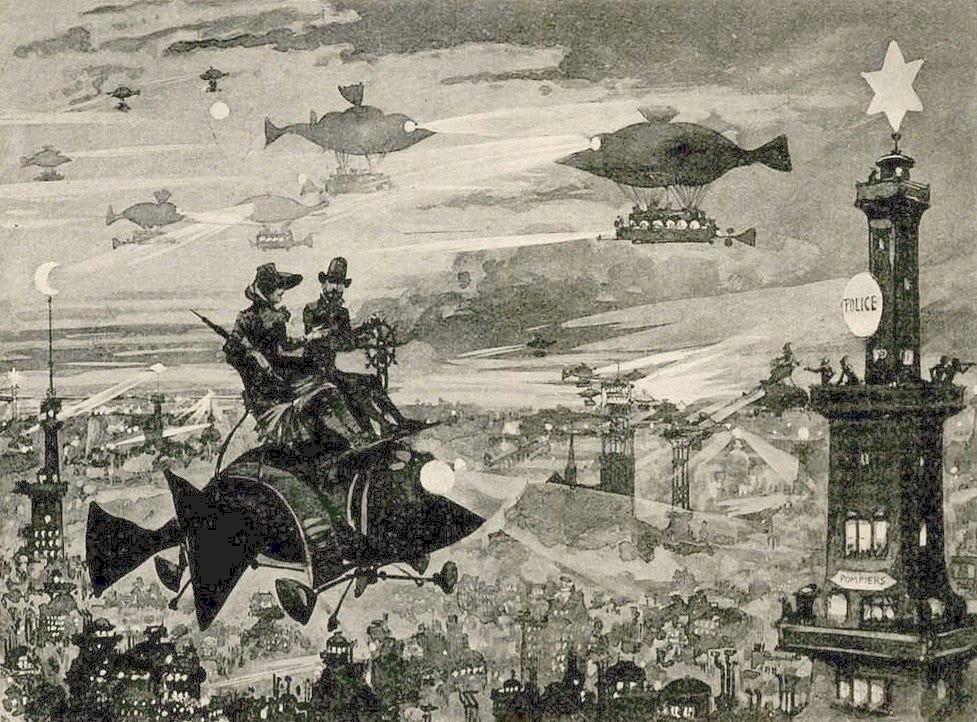

In the early 1920s, a set of 100 postcards were discovered in an abandoned French factory basement, amongst shelves of dusty novelties and circus automatons. From there they sat in an Editions Renaud, a Parisian antique shop for over half a century, until they were bought in 1978 by author Christopher Hyde. They show views of the year 2000, with personal flying machines, telescopes that could capture distant planets, robot tailors, and farms under the sea.

The illustrations had been commissioned by manufacturer Armand Gervais to celebrate the “fin de siècle festival” of 1899. Illustrator Jean Marc Côté produced a set of cards inspired in part by Jules Verne, and in part by the automatons made by the Gervais company itself.

Collated into a book nearly a century years after their conception, Isaac Asimov wrote in the introduction, “It is, of course, easy to laugh and make fun of guesses of 1899, but how would any of us do now if asked to predict life in 2085?”

Unsurprisingly, flight features predominantly throughout the series; Côté thought about numerous uses of air-based transport, including how it would affect warfare. Possibly inspired by popular toys of that era, he envisioned a helicopter-like vehicle, used as a wartime advance scout.

A stirrup-cup is the last drink a horse rider might have, with one foot in the stirrup, before mounting up to ride off. Here, a dirigible flies in the background while our pilot takes a drink before an afternoon flight. The science that keeps the plane hovering though, is unclear.

An example of the flying mail carrier trope, taking the idea of air-mail quite literally. Here the plane is more simple, like a flying bicycle, which was itself a recent innovation.

Education comes under scrutiny as books are fed into a grinder, possibly “digitised,” to be sent by electric current as sound directly to the students’ headphones. This technological teaching marvel doesn’t stop one student from looking out the window, though.

Why eat an entire plate of food when you can take save time by swallowing one tiny pill? During the 19th century, scientists discovered the chemical components of our food: fats, proteins, sugars, acids. This hypothesis then takes that one step further by taking these essential elements in pill form – a precursor to Soylent, perhaps.

The positive and optimistic potential of atomic power, portrayed here only a year after the discovery of radium in 1898. The negative effects of radiation weren’t well-known at the time. Though these negative effects would keep radioactive material from being a viable heating source in the long-term, Côté tapped into the potential of a very recent discovery here.

“Even the best futurist must face unexpected technological barriers. There are side effects he may not expect,” Isaac Asimov wrote in 1986 in the introduction to Futuredays: A Nineteenth Century Vision of the Year 2000. “Unwarranted optimism may mislead him, and so may unwarranted pessimism.”

19th-century futurists often leaned into either optimism and pessimism, with ideas at the extreme end of believability to the contemporary viewer’s eyes. The science behind the ideas may have, to put it lightly, tenuous, and the ideas are products of their time steeped in the culture and fashions of the age.

But the artists behind them, while often forgotten, have all played their parts in shaping our ideas about the future: they were pioneers peering into an unknown frontier. To their contemporary viewers, they offered for a window onto a new world of possibility and wonder – and for the first time, helped mass culture shape a collective vision of the future.

This article first appeared on Medium’s How We Get To Next. It is part of a five-part series called A Visual History of the Future.