The market is divided into supply states and buyer states, said the report published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The eastern states of Assam, Odisha and West Bengal continue to be supply states, as they always were, while Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan form the group of buyer states.

The key reason for bride trafficking, as economist Amartya Sen once put it, is “missing women”, the Indian phenomenon of preferring boys to girls. He estimated that over 100 million women were “missing” in the country.

The skewed sex ratio in a few major Indian states has given rise to an intense demand for brides from organised trafficking agencies. People in these states buy brides from poorer states, saying there are not enough women in their caste/community.

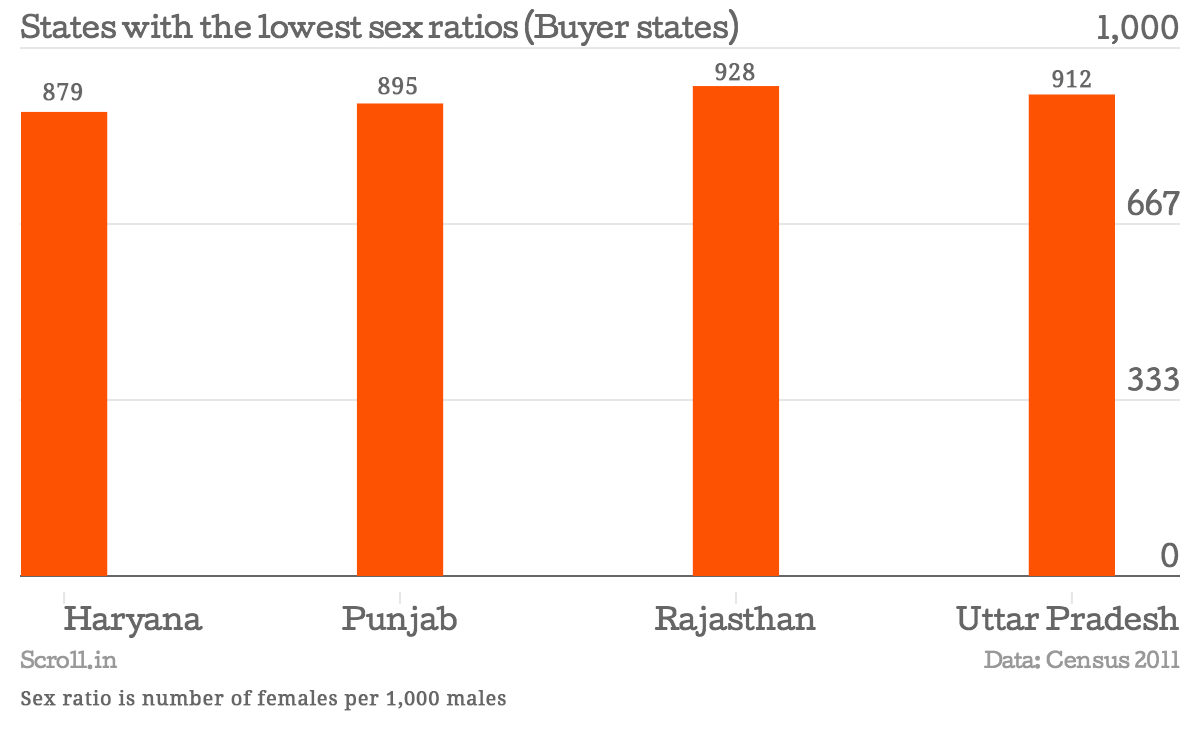

These are the states with the lowest sex ratio (number of females per 1,000 males):

The UN report says that “organised bride trafficking rings” are increasingly operating in Haryana, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh. In Punjab and Haryana, decades of unchecked sex-selective abortions have led to a significant shortage of women of “marriageable age”, a concept that is widespread there. This shortage has given rise to human trafficking as a lucrative trade, with even local villagers acting as brokers.

A study (involving more than 10,000 households) on the impact of declining sex ratios on the pattern of marriages in Haryana revealed that more than 9,000 married women were bought from other states. The study also revealed that most people now accept the concept of purchasing a bride, but deny having bought a bride themselves.

According to Empower People, a New Delhi-based organisation that focuses on issues related to women trafficking, low sex ratios are spurring the abduction of young, unmarried women.

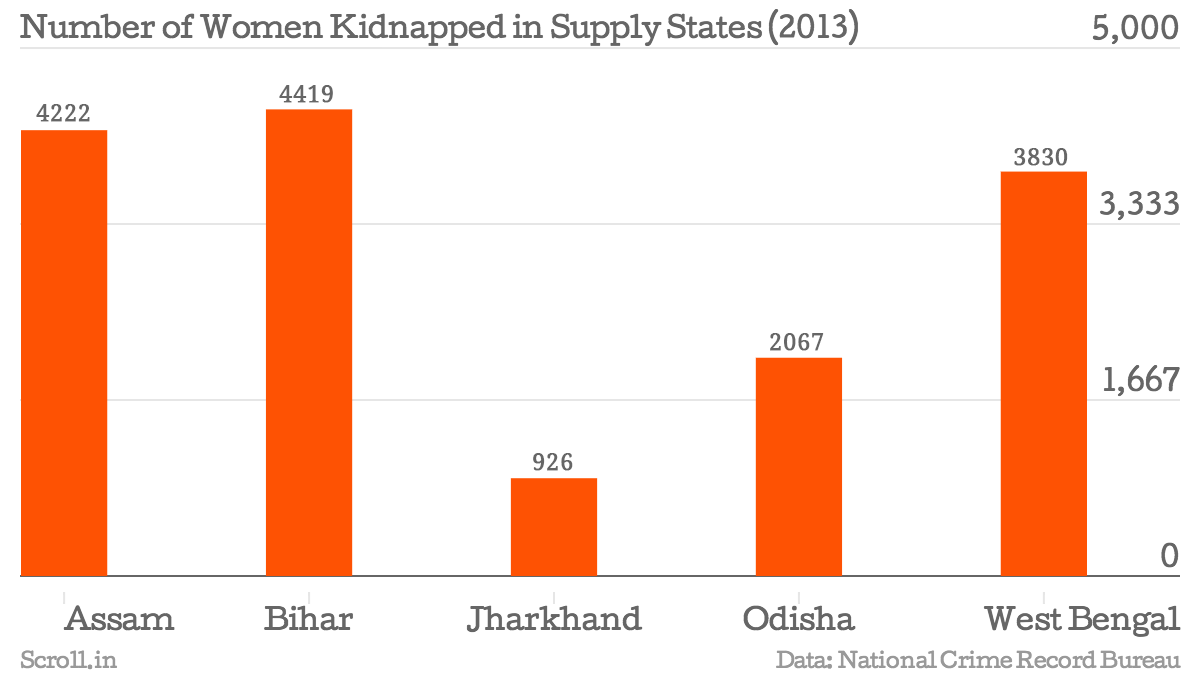

This table explains the number of women kidnapped from some states:

These states are also the “supply states”, from where women are trafficked for marriage, says the UN report. Most of the women and girls are trafficked from poor families. They are either lured by fake matrimonial dreams or lucrative jobs in booming Indian cities.

“These ‘matrimonial transactions’ are often projected as voluntary,” the report said. “However, the ‘purchased brides’ are often exploited, denied basic rights, substituted as maids or are often resold and abandoned after a few years of matrimony.”

Government's responses

An inter-ministerial group has been constituted to consider and recommend proposals to amend the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1956.

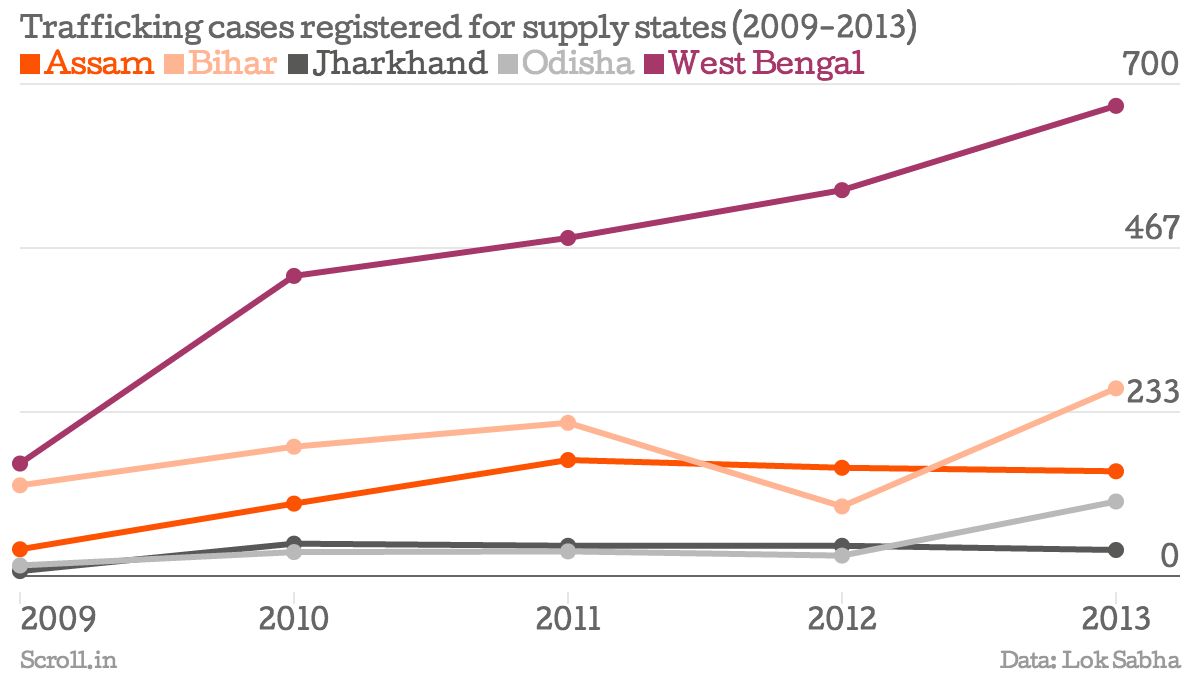

An anti-trafficking cell has been created by the Ministry of Home Affairs to strengthen enforcement. The ministry set up 225 anti-human trafficking units across India (as of August 2012), which led to an increase in registration of cases and stronger prosecution.

The government of India has strengthened the application and enforcement of the Emigration Act, 1983, to regulate recruiting agencies (agencies making fraudulent job offers overseas, fake recruitments for non-existing employers or for foreign employers who never authorised the agents, thus rendering the workers without jobs.)

Despite these actions, the reality appears unchanged.

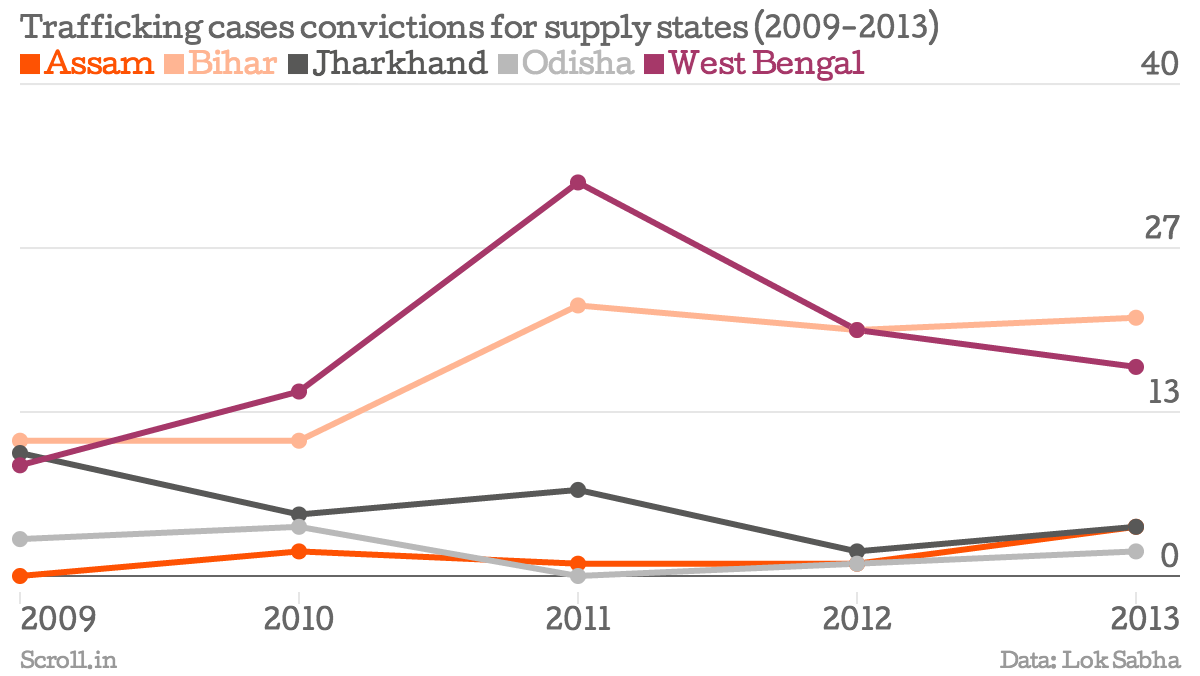

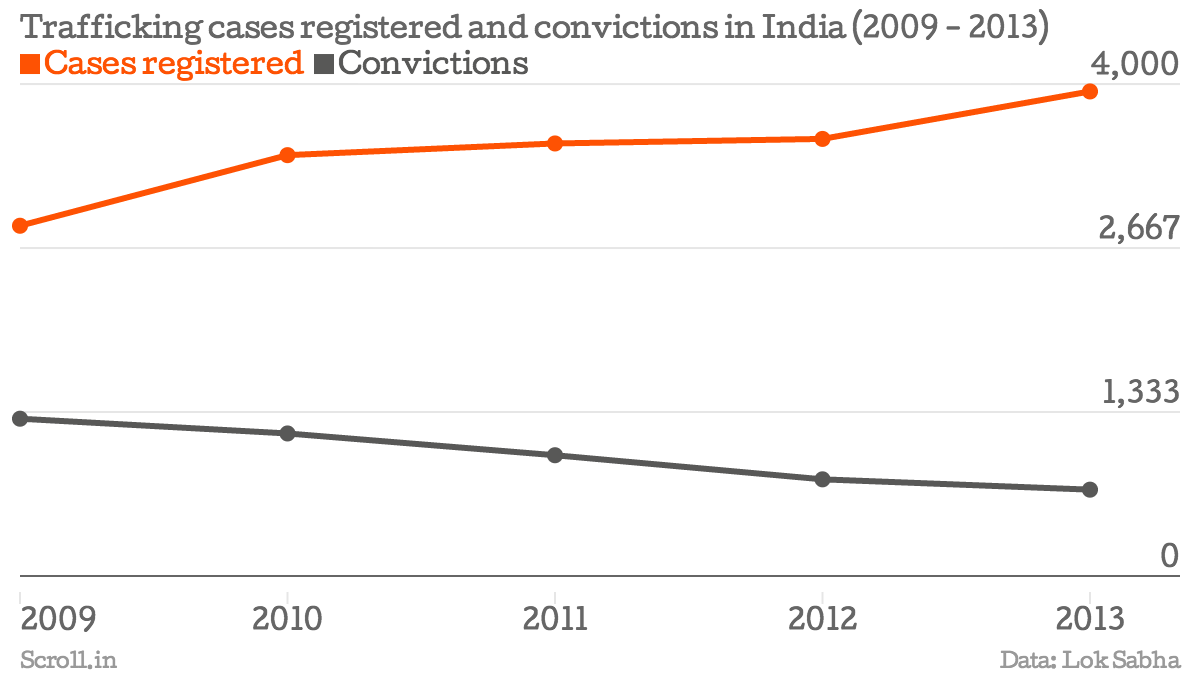

These tables show the registered trafficking cases and convictions in such cases in the supply states:

The conviction rate in India for trafficking cases was 44% in 2009, but dropped to 17% in 2013. This is alarming. In a big state like West Bengal, the conviction rate was 5.6% in 2009, declining to 2.5% in 2013. These dipping numbers highlight the gap between government policies and implementation.

This post originally appeared on IndiaSpend.com, a data-driven and public-interest journalism non-profit.