In 2016, a day before World Environment Day on June 5, Kolkata-based conservationist Meghna Banerjee received a distressing phone call about a huge gathering of hunters at the Panskura railway station in East Medinipur district, a bustling stop along the Howrah-Kharagpur railway line in West Bengal. Banerjee, a birdwatcher, was involved in rescuing animals and also engaged in anti-poaching activities.

“Initially, I did not take the call seriously, but my friend, Suvrajyoti Chatterjee, insisted that we go and investigate,” Banerjee said. “We were shocked to find at least 5,000 hunters at the railway station with multiple sacks, each containing over 50 carcasses of monitor lizards. We saw around 2,000 live animals and carcasses lying on the platform. Some people were skinning the animals and were preparing to cook them on the open platform, in full view of the railway staff and the Railway Protection Force.” This particular hunt was part of the Phalaharini Kali Pujo festival, a Hindu festival primarily celebrated among Bengali communities.

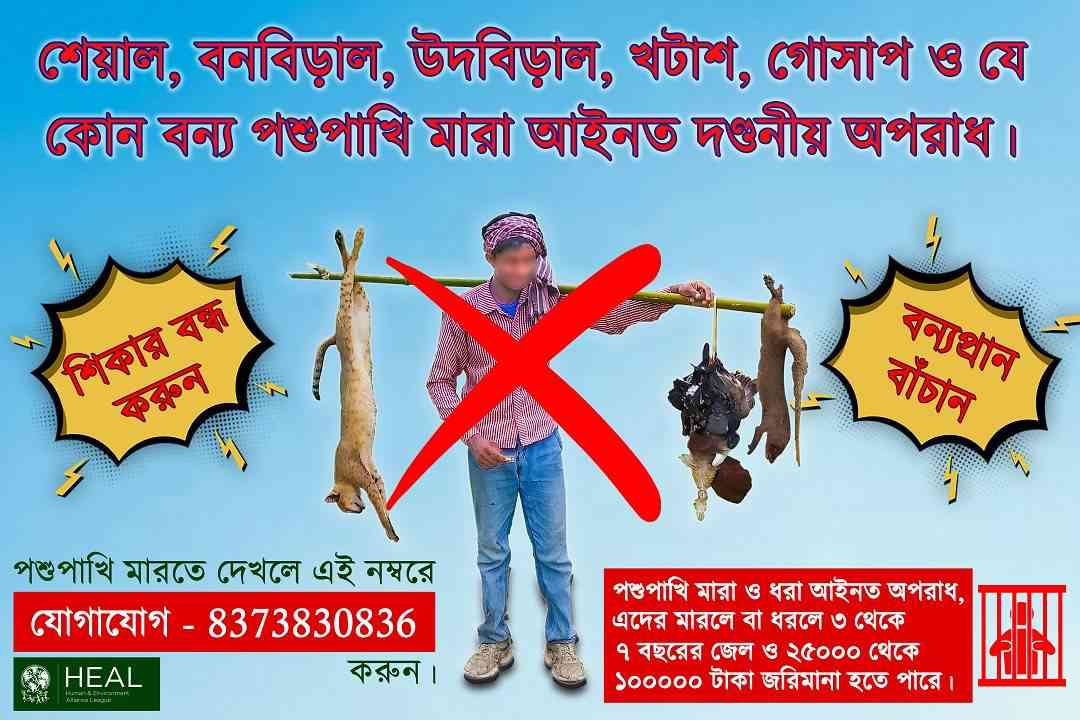

This event was the trigger for Banerjee and Chatterjee to start Human and Environment Alliance League – HEAL – in 2017, a non-profit that aims to curb rampant exploitation of wildlife and empower locals to protect their environments.

The cluster of hunting festivals known as “Shikar Utsav” start from January and continue till June. The hunting mainly coincides with the full moon. “While tribes such as Santhal, Lodha, Sabar, Oraons etc. would mainly engage in these hunts as per their rituals, many non-tribal people would also join just for ‘furti’ or fun,” Banerjee told Mongabay India. “There would be around 50 big and small hunting festivals in the year and some of the bigger ones would see gatherings of 10,000 to 15,000 hunters.”

In 2018, Banerjee, a lawyer, filed a public interest litigation seeking a ban on the hunting that takes place during the Phalaharini Kali Pujo festival. In May 2018, the Calcutta High Court passed an interim order directing the forest department, the police and the railway authorities to work together to stop the hunting during this festival.

Howrah-based animal rescuer Chitrak Pramanik said that till 2017, around 5,000 animals used to be slaughtered during the Phalaharini Kali Pujo in Howrah ranging from civets, fishing cats, monitor lizards, mongoose, squirrels, birds etc. “After the court order, there has been a drastic reduction in hunting,” Pramanik added. “In the last three years, there have been zero hunts in Howrah and East Medinipur. Now, all agencies including the forest department, police, railways and NGOs remain vigilant, and the hunters are mostly stopped and sent back from the Kolaghat bridge itself.”

Things however were different in the tribal dense Jungle Mahal districts such as Purulia, Bankura, Jhargram and West Medinipur.

In 2018, when an adult male tiger strayed into Lalgarh in the Jhargram district during the Pakhibandh hunting festival, it was allegedly killed by a spear after it mauled two members from a hunting party. This led to widespread outrage and HEAL filed another PIL, which led the Calcutta High Court to pass an embargo in 2019 on all hunting festivals in the state.

A traditional community is granted rights over wildlife and forest resources under Schedule 3 (1) of the Scheduled Tribes and other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 also known as the Forest Rights Act (FRA). The Forest Rights Act, however, specifically restricts hunting, trapping or extracting a part of the body of wild animals.

“With tribal communities having a long-standing relationship with the forest ecosystem and wildlife, often the forest department has to take a multi-pronged approach of awareness and enforcement to tackle these issues,” said Singaram Kulandaivel, Chief Conservator of Forest, Central Circle, an area where ritualistic hunts used to be common.

“If one travels 70-80 kilometres from Kolkata, an entirely different culture will be seen,” he added. “The Jungle Mahal area is a tribal-dominated area. They used to hunt for cultural reasons, which today is not a very sustainable thing to do. We are requesting people to stop hunting or else these animals will not be found in the wild in the future.”

Hunting practices

In November 2024, a study titled “Ritualistic hunts: exploring the motivations and conservation implications in West Bengal” was published in Nature Conservation. It was a socioeconomic study that aimed to understand the hunting practices in Jhargram and West Medinipur districts.

Speaking to Mongabay India, Vasudha Mishra, one of the authors and also a part of HEAL, said that they interviewed 112 individuals in these two districts (59 in Jhargram and 53 in West Medinipur). “Out of them, 99 identified themselves as hunters and the rest as non-hunters.”

The study revealed that it was mostly a traditional hunt with only two respondents admitting using guns. The hunting parties mostly comprised of 20-40 people who used traditional weapons such as spears (ballams), bows and arrows (teer dhonukh), catapults (batul, gulti), hand axes (tangi), wooden stick (lathi), snares (faand) among others.

Wild boars were the most desirable kill for the respondents followed by the Indian hare, greater coucal, quail, collared dove, yellow-footed green pigeon, jungle cat and Bengal monitor lizards.

Reduction in hunting

Following a surge in incidents of illegal hunting during traditional festivals and rising concerns from wildlife activists, the Calcutta High Court in a landmark judgement in 2023, said that killing of animals in the wild for pleasure, and the purported show of false prowess, is as heinous and culpable a crime as murder.

In the same judgement, the court ordered the formation of “humane committees” in five districts of West Bengal – West Medinipur, Bankura, Purulia, Jhargram and Mursidabad. This was later expanded to two more districts – East Bardhaman and Birbhum.

The committee was headed by the District Judge and brought together all important stakeholders under one umbrella, including the Superintendent of Police, Divisional Forest Officer, Chief Conservator of Forest, Member Secretary, District Legal Service Authority, Public Prosecutor, Wildlife Warden, a member from the tribal community, Divisional Security Commissioner, Head Quarters, Railway Protection Force of the concerned zone and Tiasa Adhya, Joint Secretary of HEAL.

Adhya, a wildlife biologist, represents the civil society and is the only person who is present in the committees of all seven districts. The court said that the committees would take steps for protection and preservation of animals in the forest and see that the animals were not killed indiscriminately, whether during hunting festivals or otherwise.

In conversation with Mongabay India, Adhya said, “Even if not unprecedented, the formation of these committees is certainly unique in the global scenario of wildlife conservation. It brings a member from those tribal communities engaging in ritualistic hunting thus involving them in conservation, while inclusion of a member from the civil society brings transparency.”

She added that some of the committees like the one in Murshidabad are doing really well, while there are also districts like East Bardhaman which are yet to form a functional committee. “Jhargram has done well by arranging a meeting with political representatives from the communities engaged in hunting,” she added. “We did not agree on everything with them but at least a conversation has been initiated. The court had directed the committees to take a strategic action plan to mitigate hunting prior to the hunting season and also a plan of action to change the attitude of these communities about hunting by engaging with them throughout the year. However, more than meetings, I would like to see the focus on engagements with communities, which is currently lacking especially in the Jungle Mahal districts.”

She added that even though the court had asked the committees to have bi-monthly meetings, barring Murshidabad, others do not have regular meetings. In 2025, only the committees in Birbhum, Purulia and West Medinipur have met so far.

However, according to a post published on Facebook by HEAL in 2024, major hunting festivals of South Bengal such as Pakhibandh, Gopegarh, Arabari, Joypur and Ajodhya Hills saw a drastic reduction in the gathering of hunters, while 10 smaller hunting festivals were called off.

Raju Sarkar, Divisional Forest Officer, Panchet said, “Apart from killing of a wild boar in Joypur there has been no reported killing of any wild animals in the last two years in my division. I’d give more credit to enforcement for the reduction in hunting. We are now getting help from other agencies, including the police and railways and trying to intercept the hunters before they enter the district.”

Meanwhile, Anjan Guha, Divisional Forest Officer of Purulia, credited the awareness campaigns by the forest department behind the reduced killing during the hunting festivals. “In the last two years, we don’t have any report of animals killed during Sendra (a tribal festival celebrated by the Santhal community),” he told Mongabay India.

“We are trying to disseminate an anti-hunting message through announcements, street plays and distributing pamphlets in Ol Chiki, a language spoken by the Santhal tribe. We do door-to-door campaigns and try to create awareness among women and children. We have organised certain sports like archery competitions instead during Sendra.”

The Sendra Parab festival which takes place in Ajodhya Pahar in Purulia district during Buddha Purnima is one of the biggest festivals of the Santhal tribe. Traditionally it coincides with one of the biggest hunting festivals of the entire Central India landscape, the Shikar Parab. The same festival is celebrated as Visu Sendra or Disom Sendra in the Dalma region of Jharkhand and as Akhand Shikar in the Simlipal hills of Mayurbhanj district of Odisha.

Rajen Tudu, spokesperson of the Bharat Jakat Majhi Pargana Mahal, one of the biggest organisations of the Santhal tribe spoke to Mongabay India about how the festival is wrongly seen as a hunting festival. “Sendra actually means search,” he said. “In the ancient times, when we used to live in the forests, we had to search for ideal habitat, food, water, medicinal plants etc. So, there used to be an annual event during which we used to search for places from where we could derive our required items.”

Tudu added that as wild animals were more in numbers back in the days, they used to hunt both as a safety measure, and as a means to derive food. “Now, Santhals don’t need to hunt because the number of wild animals have dwindled and we have got alternative sources of animal protein. Even still, our tribe gets the tag of a ‘hunters’ and the state tries to use it as an excuse to snatch our right to enter the forests.”

Explaining the connection tribals have with forests, Jagdeep Oraon, Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Tribal Studies at Sidhu-Kanho-Birsha University in Purulia told Mongabay India, that in India, one will always find tribals in forest areas. “Everything, including religion, economy and society, revolves around the forest. They eat in sal tree leaves; when they get married, their mandap is also made from a tree. In addition, their house materials are collected from forests,” he added. “The supreme deity for the Santhal community is Marang Buru, which means the God of Forests. The tribal community has a very symbiotic relation with forests. If forests are still surviving in India, it is only because of the tribals.”

Way ahead

Banerjee said that while the reduction in hunting is an encouraging development, they are yet to achieve the target of zero hunts in Jungle Mahal. “Now, HEAL has a dedicated team of around 150 volunteers who monitor and report these hunts,” she said.

“HEAL members have faced physical threats on ground while trying to stop the hunters because many of them are in an inebriated state and become quite aggressive.” Banerjee also shared that this year, they have reports of 10,000 to 15,000 people assembling in a big hunt in the Bankura district. They received reports of wild boars, jungle cats and rabbits being killed in these hunts.

Pradeep Vyas, former Principal Chief Conservator of Forest, Wildlife, West Bengal, said that according to the Wildlife Protection Act 1972, hunting is illegal and there is no concession for any community in this regard. “However, some tribal communities believed in their right to hunt and if the forest department tried to stop them, they were seen as anti-tribal. Gradually awareness was raised among these communities and the authorities now have socio-legal rights to stop these hunts,” he added. “They always had the legal rights, but as long as they do not get support from the society, implementation of any law becomes difficult.”

Speaking to Mongabay India, Raza Kazmi, wildlife historian and conservationist expressed fear that unregulated hunting might lead to decimation of wildlife and empty forests with no animals.

Giving the example of the Bison Maria tribe in Bastar, Chhattisgarh, he said, “Bison Marias have this culture of wearing bison horns as headgear during their traditional dance. In this process, they wiped off the entire bison population in Bastar… now they are using plastic or wooden horns.” Kazmi also added that there is still a huge gap in awareness regarding wildlife conservation in the Central India region encompassing Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and parts of West Bengal.

This article was first published on Mongabay.